Mining trucks navigate the scarred terrain of a massive copper pit in the Democratic Republic of Congo as we investigate and research about Africa Shell Companies Mining, their mechanical thunders echo across the landscape that holds some of Earth’s most coveted minerals.

Yet for all the wealth being extracted from African soil, much of the profit vanishes into a global network of anonymous shell companies, phantom entities that exist only on paper but wield enormous power over the continent’s resource sector.

Aerial view of a large African open-pit cobalt and copper mine showing the scale and environmental impact of resource extraction. Image Credit: New Scientist

An extensive investigation spanning eight months has uncovered the intricate web of shell companies that control vast swaths of Africa’s mining industry, systematically draining billions in revenue that should benefit local populations. Through leaked documents, court records, and testimonies from industry insiders, this investigation exposes how these paper entities facilitate corruption, tax evasion, and the theft of natural resource wealth on an unprecedented scale.

The Architecture of Exploitation

The mechanics of shell company operations in African mining follow a familiar pattern across the continent. Complex ownership structures, often spanning multiple jurisdictions, obscure the true beneficiaries of mining operations while facilitating the movement of profits away from African treasuries.

“What we’re seeing is the systematic capture of Africa’s mineral wealth through legal structures designed to maximize opacity,” explains Dr. Khadija Sharife, a specialist in illicit financial flows who has tracked mining corruption across the continent. “These shell companies don’t just hide beneficial ownership , they actively facilitate the extraction of value from African economies.”

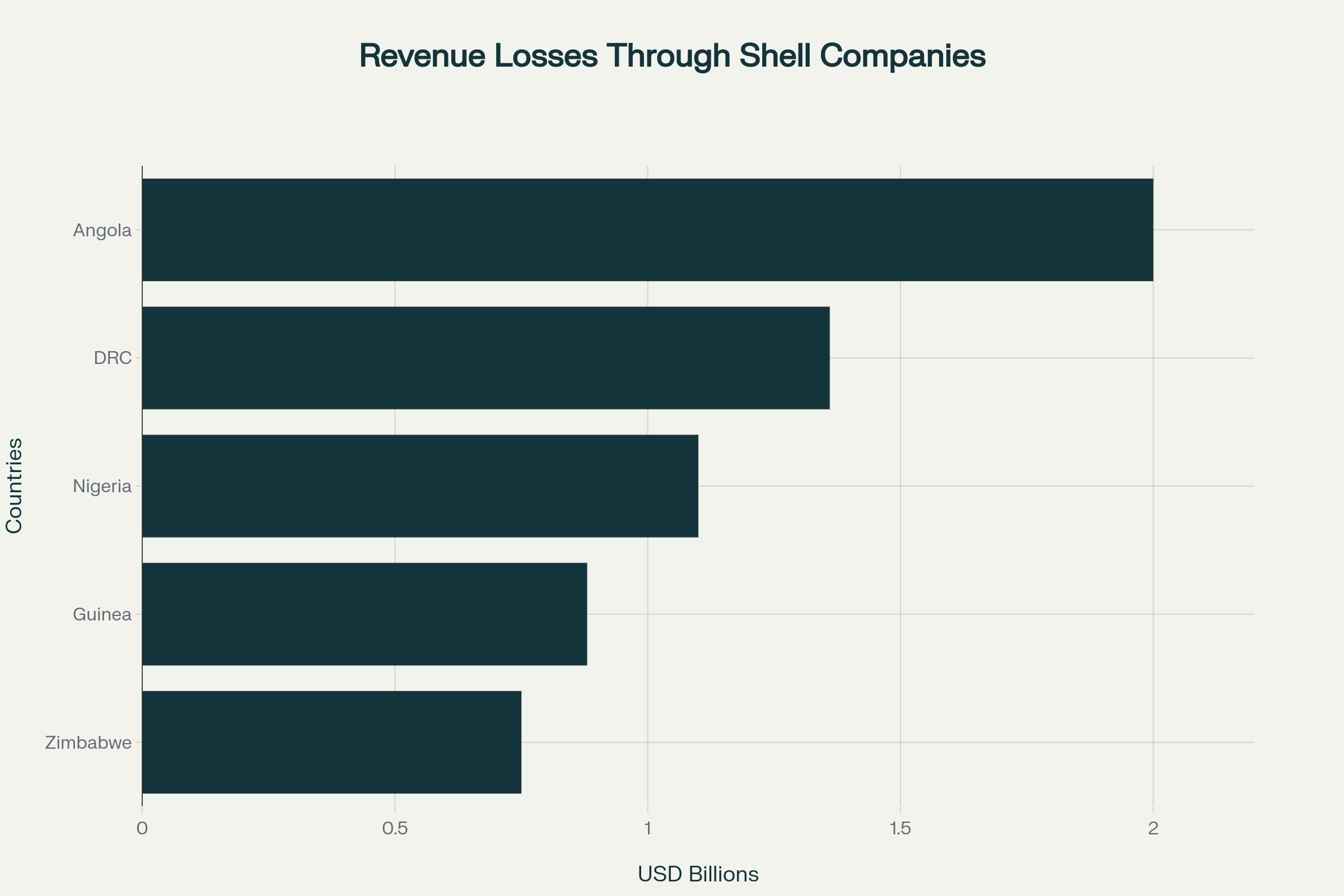

The scope of the problem is staggering. Conservative estimates suggest that shell companies drain approximately $6.5 billion annually from African mining revenues through various mechanisms including transfer pricing manipulation, phantom service contracts, and beneficial ownership concealment.

Revenue losses across African countries from shell company operations in mining and oil sectors

The Democratic Republic of Congo: Ground Zero for Resource Theft

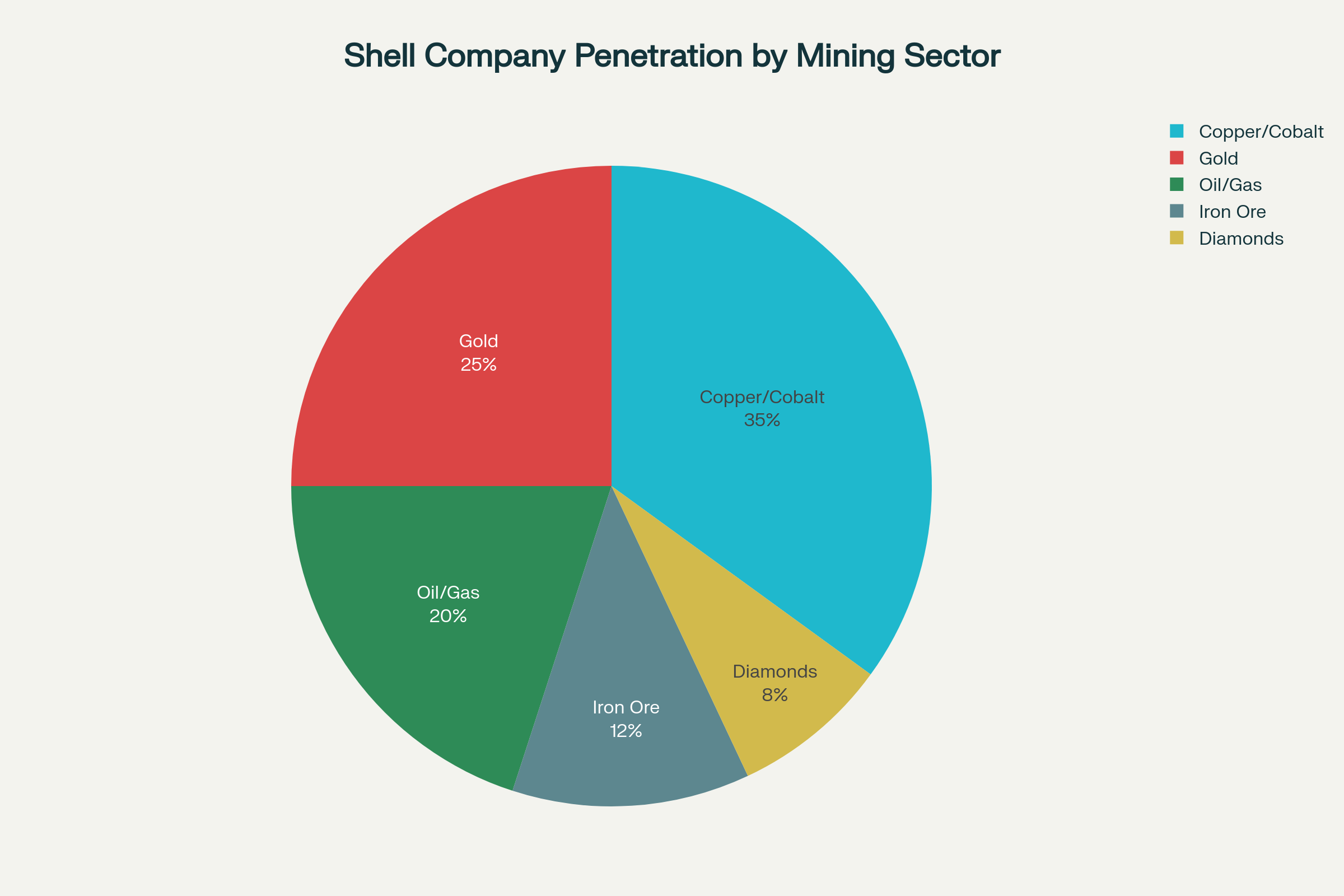

In the eastern provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo, where global demand for cobalt and copper has sparked a modern-day mineral rush, shell companies have perfected the art of resource extraction through ownership obfuscation.

Court documents obtained during this investigation reveal how a network of companies linked to Israeli billionaire Dan Gertler systematically undervalued mining assets in the DRC, resulting in losses exceeding $1.36 billion to the state treasury between 2010 and 2012 alone. The scheme involved a complex web of offshore entities that purchased mining concessions at fractions of their market value before reselling them at full price to international mining companies.

“The money that should have built schools and hospitals in Congo instead lined the pockets of politically connected elites and their offshore partners,” states Jason Stearns, director of the Congo Research Group. The lost revenue from just five deals during this period nearly doubled the country’s combined annual budgets for health and education.

Local communities bear the direct cost of this financial engineering. In the mining town of Kolwezi, where global cobalt production centers, residents lack access to clean water despite sitting atop mineral wealth worth billions.

Artisanal miners working under harsh conditions in the cobalt mining sites of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Image Credit: Think Landscape

Marie Kasongo, a mother of four from Kolwezi, describes the bitter irony: “We see the trucks carrying away our wealth every day, but we still fetch water from contaminated wells. Where does all this money go?”

Nigeria’s Phantom Oil Empire

Nigeria’s experience with the Malabu Oil scandal demonstrates how shell companies can capture entire sectors of a nation’s resource economy. In 2011, oil giants Shell and Eni paid $1.1 billion to the Nigerian government for offshore block OPL 245, one of West Africa’s largest oil fields. However, investigations revealed that the money was immediately transferred to Malabu Oil & Gas, a phantom company secretly owned by former oil minister Dan Etete.

Internal Shell documents obtained through court proceedings show company executives knew precisely where their payment would end up. “The ambit claim emanating from Abuja is that the price to Etete is $2bln,” one internal Shell document stated. “However, in the lead up to the elections, we believe that a figure in the range of $1-1.2bln will be accepted.“

The revelation that Shell executives were aware of the corruption allegations for six years while denying any wrongdoing illustrates the complicity of international corporations in these schemes. The OPL 245 block contains an estimated nine billion barrels of oil reserves, yet none of the revenue has benefited ordinary Nigerians.

Offshore oil drilling platform in Nigeria symbolizing the infrastructure linked to resource extraction and the Malabu scandal. Image Credit: Offshore Technology

“This is not just corruption – it’s the systematic theft of a nation’s future,” argues Adetokunbo Mumuni of the Socio-Economic Rights and Accountability Project in Lagos. “When oil revenues disappear into shell companies, it means fewer resources for education, healthcare, and infrastructure.”

Angola’s Offshore Empire

The “Luanda Leaks” investigation exposed how Isabel dos Santos, daughter of former Angolan president José Eduardo dos Santos, built a $2 billion business empire through a network of more than 400 companies and subsidiaries across 41 jurisdictions. This sprawling offshore network enabled the systematic looting of Angola’s oil wealth, with state-owned Sonangol serving as the primary vehicle for fund transfers.

Between 2007 and 2010, an International Monetary Fund audit found that $32 billion in oil revenues representing a quarter of the state’s total revenue simply disappeared from official records. The missing funds could have transformed Angola’s development trajectory, yet instead enriched a small circle of politically connected elites and their offshore vehicles.

Women washing clothes in muddy water near makeshift shelters in a mining-affected community in the DRC. Image Credit: Business Human Rights

Dr. Ricardo Soares de Oliveira, author of “Magnificent and Beggar Land,” notes: “Angola represents the perfect storm for shell company abuse – massive resource rents, weak institutions, and a ruling elite with unfettered access to offshore financial systems”.

The Global Shell Company Network

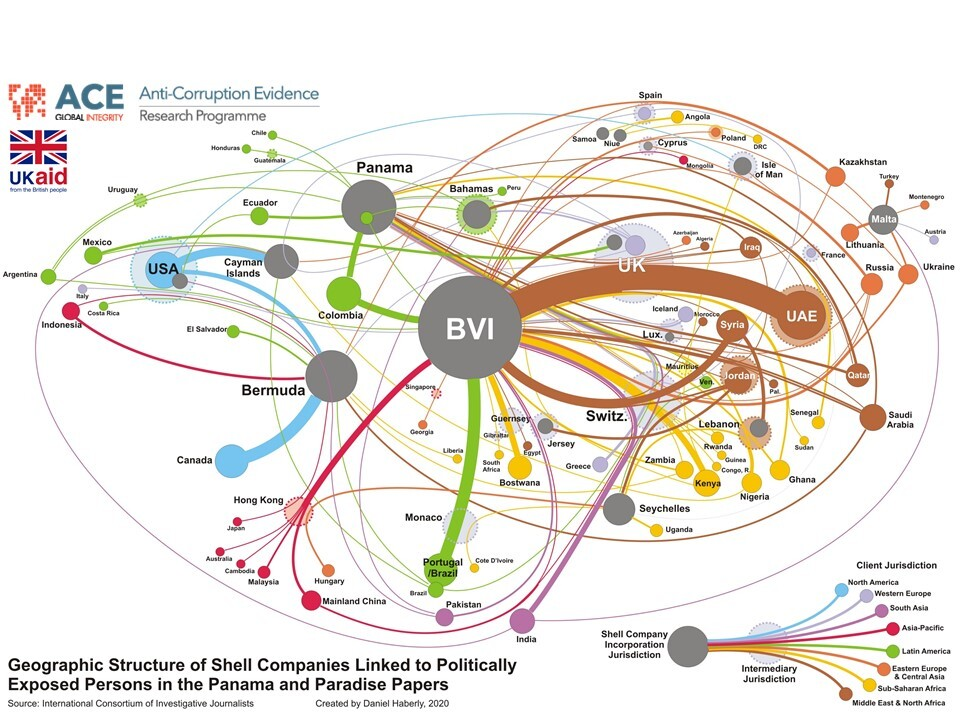

The Panama Papers and subsequent leaks have illuminated the global infrastructure that supports African resource extraction through anonymous companies. An analysis of leaked documents reveals that 73 percent of shell companies involved in African mining deals were incorporated in just five jurisdictions: British Virgin Islands, Panama, Mauritius, Seychelles, and the Cayman Islands.

Network diagram showing how politically exposed persons use shell companies across global jurisdictions with central hubs in the British Virgin Islands, Panama, and others. Image Credit: GIACE

This network operates with sophisticated legal and financial architecture. Beneficial ownership is often obscured through multiple layers of holding companies, nominee directors, and trust structures. The complexity is intentional – the more opaque the ownership chain, the more difficult it becomes for African governments, civil society, or international investigators to trace the flow of resources.

The Mauritius Gateway

Mauritius has emerged as a particularly important hub for African mining shell companies, offering a combination of favorable tax treaties, financial secrecy, and proximity to African markets. More than 60 percent of foreign direct investment into Africa is channeled through Mauritius-based entities, many of which are little more than brass plate companies.

Zimbabwe provides a stark example of Mauritius-based shell company operations. The Sentry investigation tracked how businessman Kudakwashe Tagwirei used a complex network of Mauritius-based entities to control vast mining assets while avoiding US sanctions. When sanctions were imposed in 2020, Tagwirei’s assets were quickly transferred to another Mauritius company, Quorus Management Services, with the ultimate beneficial ownership remaining obscured behind corporate secrecy laws.

“The use of Mauritius as a conduit for African mining investments has reached epidemic proportions,” explains Alex Cobham of the Tax Justice Network. “What we’re seeing is the wholesale capture of African resources through legal structures designed in offshore jurisdictions.”

The Human Cost of Corporate Opacity

Beyond the financial losses lie devastating human consequences. Shell companies don’t just hide beneficial ownership – they obscure accountability for environmental damage, worker safety violations, and community displacement.

Fishermen working together to haul a large fish catch in coastal waters, highlighting community involvement in resource extraction. Image credit: NYTIMES

In Guinea’s Boké region, testimony from a whistleblower supported by the Platform for the Protection of Whistleblowers in Africa reveals how Orion Resource Partners, a New York-based investment fund, used opaque corporate structures to evade environmental regulations and bribe officials. When a barge chartered by subsidiary Alufer Mining spilled 7,500 tons of bauxite into the ocean in June 2023, the company’s complex ownership structure made accountability nearly impossible to establish.

“I’ve been sickened over the months by everything I’ve seen,” the whistleblower, known as “Alpha,” testified. “All I wanted was to contribute to the development of my country by providing my expertise in the mining sector. Instead, I witnessed systematic attempts to circumvent Guinean regulations.”

Environmental Devastation and Shell Company Impunity

The Niger Delta provides perhaps the most tragic example of how shell companies enable environmental destruction without accountability. Over five decades of oil extraction have left the region’s ecosystem devastated, with local communities bearing the cost while profits flow to offshore entities.

Man stands amid polluted water and debris in a rural area surrounded by palm trees, highlighting environmental impacts of resource extraction. Image Credit: Bloomberg

Shell Petroleum Development Company, despite being a subsidiary of Royal Dutch Shell, operates through a complex joint venture structure with the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation that has historically obscured responsibility for oil spills and environmental cleanup. The result has been widespread contamination of water, soil, and air affecting millions of people.

Dr. Godwin Ojo of Environmental Rights Action explains the connection between corporate structure and environmental impunity: “When ownership is opaque and accountability is diffused through shell companies, environmental crimes become someone else’s problem. Communities suffer while profits are extracted through legal structures designed to avoid responsibility.”

Comparative Perspectives: Lessons from Other Regions

Africa’s experience with shell companies in extractive industries mirrors patterns observed globally, but with particularly severe consequences due to weak regulatory frameworks and high levels of corruption.

Latin America’s Regulatory Response

Countries like Chile and Peru have implemented beneficial ownership registries specifically for mining companies, requiring disclosure of all individuals owning more than 5 percent of extractive companies. Chile’s registry, established in 2019, has successfully identified numerous previously hidden ownership structures in the copper sector.

“What Chile demonstrates is that beneficial ownership transparency is not just possible in the extractive sector – it’s essential,” notes Maíra Martini of Transparency International. “When you can see who really owns and controls mining companies, you can begin to address corruption and ensure revenues benefit citizens.”

The Nordic Model

Norway’s approach to extractive industry transparency provides another instructive contrast. The country’s beneficial ownership register covers all companies operating on Norwegian territory, with particularly stringent requirements for petroleum sector entities. Combined with strong rule of law and enforcement mechanisms, this system has effectively eliminated the shell company abuse common in developing countries.

“The Norwegian model shows that transparency without enforcement is meaningless,” argues Siri Gloppen of the Chr. Michelsen Institute. “You need both disclosure requirements and the institutional capacity to act on that information.”

The Shell Company Ecosystem

Shell companies in African mining operate within a sophisticated ecosystem of enablers, including international banks, law firms, accounting companies, and incorporation agents. This network provides the professional services necessary to establish and maintain complex ownership structures across multiple jurisdictions.

Distribution of mining assets controlled by shell companies across different resource sectors in Africa

Banking’s Role in Resource Theft

Major international banks play a crucial role in facilitating shell company operations through correspondent banking relationships and private banking services. The FinCEN Files revealed how banks including Standard Chartered, HSBC, and JPMorgan Chase processed billions in transactions flagged as suspicious, many linked to African resource extraction through shell companies.

Internal documents from these investigations show bank employees were aware of the suspicious nature of many transactions but processed them regardless. In one case, Standard Chartered processed $20 million in payments from a known shell company involved in DRC mining deals despite compliance officers flagging the transactions as high-risk for money laundering.

Professional Services Network

The “Big Four” accounting firms – PwC, Deloitte, EY, and KPMG – have repeatedly been implicated in creating and maintaining shell company structures for African mining operations. These firms provide legitimacy to complex ownership arrangements while arguing they are simply following client instructions within existing legal frameworks.

A former PwC partner, speaking on condition of anonymity, explains the internal dynamics: “There’s enormous commercial pressure to provide whatever structures clients want, especially for large mining accounts. Questions about beneficial ownership or the purpose of complex structures are not welcomed.”

Technology and Shell Company Detection

Advances in data analytics and blockchain technology offer new possibilities for identifying and tracking shell company operations in African mining. Several initiatives are using artificial intelligence to analyze corporate networks and identify suspicious ownership patterns.

The Africa Mining Vision, adopted by the African Union in 2009, calls for the use of technology to enhance transparency and accountability in the sector. However, implementation has been slow, with most African countries lacking the technical capacity and political will to deploy sophisticated tracking systems.

Christian-Géraud Neema, an expert on African strategic minerals, argues: “African stakeholders need to invest in more applied research to understand this industry, including the technology behind modern financial engineering. We stand to lose out again if we don’t think several steps ahead”.

Regulatory Capture and Political Economy

The persistence of shell company abuse in African mining cannot be understood without examining the political economy that enables it. In many resource-rich African countries, political elites benefit directly from opaque ownership structures, creating powerful incentives to maintain the status quo.

Professor Tim Kelsall of the Overseas Development Institute explains: “Shell companies don’t just hide beneficial ownership from the public – they often hide it from rival political factions. This creates a form of insurance for ruling elites, ensuring their resource wealth remains protected even if political power shifts”.

This dynamic is particularly evident in countries like Equatorial Guinea, where the ruling Obiang family has used shell companies to accumulate vast mining and oil assets while maintaining plausible deniability about their wealth.

The Response: Transparency Initiatives and Their Limitations

Various transparency initiatives have emerged to address shell company abuse in African mining, with mixed results. The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) now requires member countries to disclose beneficial ownership information for extractive companies, but implementation remains uneven.

Nigeria became the first African country to establish a public beneficial ownership register for extractive industries in 2019, covering 56 companies. However, the register remains limited to the extractive sector and lacks verification mechanisms to ensure accuracy of disclosed information.

“Publishing information is just the first step,” notes Elisa Peter of Open Ownership. “Without verification, enforcement, and use of the data for investigation and prosecution, transparency becomes a box-ticking exercise rather than a tool for accountability.”

Ghana’s Ongoing Struggles

Ghana’s experience illustrates the challenges of implementing beneficial ownership transparency even in relatively well-governed African countries. The controversial Agyapa Royalties deal, structured through Jersey-based shell companies, sparked national protests despite Ghana’s membership in transparency initiatives.

The deal would have seen Ghana’s future gold royalties sold to offshore investors through a complex structure designed to obscure beneficial ownership. Only sustained civil society pressure and media investigation forced the government to suspend the arrangement.

“The Agyapa deal shows that transparency laws mean nothing without active civil society monitoring,” argues Dr. Steve Manteaw of the Ghana Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative.

Economic Impact and Development Consequences

The macroeconomic impact of shell company operations in African mining extends far beyond simple revenue loss. By facilitating tax avoidance and profit shifting, these structures reduce government revenues needed for public investment in infrastructure, education, and healthcare.

A 2019 study by the Tax Justice Network estimated that African countries lose $88.6 billion annually to illicit financial flows, equivalent to 3.7 percent of continental GDP. Much of this loss stems from extractive industry operations channeled through shell companies.

The development consequences are particularly severe for countries heavily dependent on mining revenues. In Zambia, where mining accounts for 72 percent of export earnings, shell company abuse has contributed to persistent poverty despite significant copper wealth.

“When mining revenues disappear offshore through shell companies, the resource curse becomes self-fulfilling,” explains Professor Paul Collier of Oxford University. “Countries remain poor not because they lack resources, but because the benefits of those resources are captured by a small elite and their offshore vehicles.”

Corporate Due Diligence and Supply Chain Responsibility

International companies sourcing materials from African mines increasingly face pressure to ensure their supply chains are free from corruption and human rights abuses. However, shell company ownership makes such due diligence extremely difficult.

Tesla’s cobalt supply from the DRC illustrates these challenges. Despite implementing extensive due diligence procedures, the company’s cobalt supply chain includes material from mines where beneficial ownership remains opaque and community consultation has been minimal.

“You can’t do meaningful due diligence when you don’t know who really owns and controls the mines in your supply chain,” argues Lauren Compere of Boston Common Asset Management. “Shell companies make responsible sourcing nearly impossible.”

Legal Frameworks and Enforcement Challenges

African legal systems generally lack the capacity to investigate and prosecute complex shell company schemes. Most countries have limited resources for financial crime investigation, while shell company structures often span multiple jurisdictions beyond African court authority.

The few successful prosecutions have typically relied on international cooperation and foreign legal proceedings. The ongoing Simandou iron ore investigation in Guinea, involving alleged corruption by BSGR through shell companies, has proceeded primarily through Swiss and UK courts rather than Guinea’s judicial system.

“African judiciaries need significant capacity building to handle modern financial crimes,” argues Justice Mogoeng Mogoeng, former Chief Justice of South Africa. “Shell company schemes exploit the gaps between different legal systems, requiring new forms of international cooperation.”

Civil Society Response and Investigative Capacity

African civil society organizations have emerged as crucial actors in exposing shell company abuse, despite facing significant resource constraints and sometimes violent opposition. Organizations like the Platform for the Protection of Whistleblowers in Africa have played vital roles in supporting insiders willing to expose corruption.

However, civil society faces enormous challenges in investigating complex corporate structures. Most organizations lack the technical capacity and financial resources needed to trace beneficial ownership across multiple jurisdictions.

“We’re fighting billion-dollar shell company schemes with shoestring budgets and basic technology,” explains Aisha Dodwell of Global Witness. “African civil society needs significant support to level the playing field with international corporate networks.”

The Way Forward: Recommendations and Reform Pathways

Addressing shell company abuse in African mining requires coordinated action across multiple levels, from local transparency initiatives to international regulatory reform.

Immediate Reforms

Beneficial Ownership Registries: All African countries should establish public beneficial ownership registries covering extractive companies, with verification requirements and meaningful penalties for false declarations.

Contract Transparency: Mining contracts and licenses should be published in full, including all side agreements and amendments that might obscure true terms.

Revenue Transparency: Real-time publication of government revenues from extractive companies, disaggregated by project and payment type.

Structural Changes

Regional Cooperation: African regional bodies should establish information-sharing mechanisms to track shell company operations across borders.

International Reform: OECD countries should eliminate the secrecy jurisdictions that enable shell company abuse, beginning with public beneficial ownership registries in all G20 countries.

Supply Chain Due Diligence: International companies should be legally required to disclose beneficial ownership throughout their supply chains.

Technological Solutions and Innovation

Blockchain technology and artificial intelligence offer new possibilities for tracking beneficial ownership and detecting suspicious corporate structures. Several African countries are piloting blockchain-based land registries that could be extended to cover mining concessions and ownership structures.

Rwanda’s digital transformation provides a model for how technology can enhance transparency. The country’s unified business registration system, launched in 2020, automatically flags companies with complex ownership structures or connections to politically exposed persons.

“Technology won’t solve the shell company problem by itself, but it can make corruption much more difficult and expensive,” notes Bitange Ndemo, former Permanent Secretary in Kenya’s Ministry of Information and Communications.

International Cooperation and Enforcement

Shell company abuse in African mining requires international cooperation for effective enforcement. Most shell companies are incorporated in offshore jurisdictions beyond African legal authority, while the financial institutions enabling these schemes are typically regulated by developed countries.

The UK’s recent passage of the Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act provides a model for how developed countries can address their role in enabling shell company abuse. The Act requires UK companies to verify beneficial ownership information and increases penalties for false filings.

“What’s needed is a global approach that treats shell company abuse as the international crime it really is,” argues Eva Joly, former investigating magistrate in France. “African countries can’t solve this problem alone when the infrastructure enabling abuse is located in Western financial centers.”

The Role of International Financial Institutions

International financial institutions, including the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, have begun incorporating beneficial ownership transparency requirements into their lending programs. However, enforcement remains weak, with few examples of loans being cancelled due to transparency violations.

A World Bank official, speaking on background, acknowledges the limitations: “We can include transparency requirements in our loan agreements, but we don’t have the capacity to verify beneficial ownership information or investigate complex corporate structures. We’re essentially relying on borrower self-certification.”

Media and Investigative Journalism

African investigative journalism has played a crucial role in exposing shell company abuse, despite facing significant resource constraints and sometimes violent intimidation. The collaboration between international and local journalists in investigations like the Panama Papers and Luanda Leaks demonstrates the potential for cross-border investigative work.

However, most African media organizations lack the technical capacity and financial resources needed for complex financial investigations. International support for African investigative journalism capacity is essential for sustained accountability efforts.

“Local journalists understand the political and economic context that international investigators often miss,” explains Khadija Patel, editor of Mail & Guardian Africa. “But we need better training and resources to follow the money trail through complex corporate structures.”

Educational and Capacity Building Needs

Understanding shell company operations requires specialized knowledge of corporate law, accounting, and international finance that is often lacking in African institutions. Universities and professional training programs need significant enhancement to build local capacity for investigating financial crimes.

The University of Cape Town’s Graduate School of Business has pioneered courses on extractive industry governance, but similar programs are rare across the continent. Building this expertise is essential for creating the human capital needed to address shell company abuse.

“We need a generation of African professionals who understand how modern financial engineering works and can hold international corporations accountable,” argues Professor Yash Ramkolowan of the University of the Witwatersrand.

Community Engagement and Local Ownership

Addressing shell company abuse ultimately requires engagement with the communities most affected by extractive operations. Local communities often have the most direct knowledge of mining operations and the strongest incentives to ensure revenues benefit local development.

However, most transparency initiatives focus on national-level disclosure rather than community engagement. Creating mechanisms for communities to access and use beneficial ownership information is essential for effective accountability.

“Communities need the tools and information to hold mining companies accountable at the local level,” argues Godwin Ojo of Environmental Rights Action. “Transparency that doesn’t reach affected communities is meaningless.”

Economic Alternatives and Diversification

Reducing dependence on extractive industries may be the ultimate solution to shell company abuse. Countries with diversified economies are less vulnerable to resource capture through opaque corporate structures.

Rwanda’s economic diversification strategy, focused on services and manufacturing, provides a model for how resource-dependent economies can reduce their vulnerability to extractive industry corruption. While Rwanda has limited mineral resources compared to neighbors like the DRC, its approach to economic governance offers lessons for other African countries.

“The best defense against shell company abuse may be economic diversification that reduces dependence on extractive rents,” suggests Dr. Carlos Lopes, former Executive Secretary of the UN Economic Commission for Africa.

Conclusion and Call to Action

The shell company networks controlling vast swaths of Africa’s mining wealth represent one of the continent’s greatest development challenges. These legal phantoms don’t just hide beneficial ownership – they facilitate the systematic theft of resources that could transform African societies.

The evidence presented in this investigation demonstrates that shell company abuse is not a technical problem requiring technical solutions. It is a political economy challenge that benefits powerful elites at the expense of ordinary African citizens. Addressing it requires political will, international cooperation, and sustained pressure from civil society.

The cost of inaction is measured not just in billions of dollars in lost revenue, but in the foregone opportunities for development, the perpetuation of poverty amidst mineral wealth, and the degradation of democratic governance. African countries cannot achieve sustainable development while their resource wealth flows through opaque corporate structures to offshore accounts.

The time for cosmetic transparency reforms has passed. What is needed now is fundamental change in how Africa’s mineral wealth is governed, extracted, and distributed.

Citizens, civil society organizations, journalists, and policymakers across Africa and internationally must demand an end to the shell company schemes that perpetuate the resource curse. This means supporting beneficial ownership transparency, strengthening investigative capacity, and holding both African governments and international corporations accountable for their role in perpetuating these systems.

The mineral wealth beneath African soil belongs to African people. It is time to ensure that wealth serves development rather than enriching anonymous shell companies and their hidden beneficiaries. The future of African development may well depend on winning this fight for transparency and accountability in the extractive industries.

The evidence is clear, the mechanisms are exposed, and the human cost is undeniable. What remains is the political will to act. Africa’s mineral wealth can be a blessing rather than a curse, but only if the shell companies that currently capture it are finally brought into the light.

Citations and Sources

Citations have been made in respective sections. Should you cite an error, kindly email ed****@*****na.com with the link to this article and the changes suggested.

Partner With Us for Impactful Change

Ready to drive transparency and accountability in your sector?

Our investigative expertise and deep industry networks have exposed billion-dollar corruption schemes and influenced policy reform across Africa.

Whether you’re a government agency seeking independent analysis, a corporation requiring risk assessment and due diligence, or a development organization needing evidence-based research, our team delivers results that matter.

Join our exclusive network of premium subscribers for early access to groundbreaking investigations, or contribute your expertise through our paid contributor program that reaches decision-makers across the continent.

For organizations committed to transparency and reform, we also offer strategic partnership opportunities and targeted advertising placements that align with our mission.

Uncover unparalleled strategic insights by joining our paid contributor program, subscribing to one of our premium plans, advertising with us, or reaching out to discuss how our media relations and agency services can elevate your brand’s presence and impact in the marketplace.

Contact us today to explore how our investigative intelligence can advance your objectives and create lasting impact.