Reality TV markets itself as an unscripted, authentic peek into contestants’ lives, but rising evidence shows the stage is often set with deception. Contestants in talent competitions, dating shows, and survival contests worldwide are reporting exploitative clauses in their contracts that strip them of promised rewards and basic rights. Investigative reporting has uncovered cases of unpaid prizes, secret fees, coerced confessions and draconian non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) that collectively amount to financial and psychological fraud.

This exposé digs deep into the frauds behind Reality TV Contracts, comparing practices in the US, UK, India, Korea and beyond, and includes testimony from former contestants, legal experts and media analysts. It unpacks real cases – class-action lawsuits, government complaints, and whistleblower statements – to reveal how reality TV “dream jobs” can become nightmarish contracts.

Reality stars and industry insiders alike are now questioning the ethics of these shows. SAG-AFTRA and other unions are even considering organizing reality contestants to secure fair pay and protections. In the U.K., media outlets have reported that participants on shows like Love Island and The X Factor have long complained about onerous agreements.

In India, a 120-page Bigg Boss contract demands absolute silence under threat of losing all earnings. South Korean contestants – including a Netflix Squid Game: The Challenge champion – have publicly demanded millions of dollars in prize money that production withheld until after the show aired. These high-profile instances highlight a systemic problem: contestants are lured by fame or cash, but find themselves legally trapped.

The following sections examine three main fraud patterns in contestant contracts: hidden financial traps, psychological manipulation on set, and illegal clauses like extreme NDAs and gag orders. We include infographics and images to illustrate how much money contestants truly make – if any – and quotes from those who risked it all.

We also compare how different countries handle these contracts, from US and UK litigation to Indian and Korean show regulations. By revealing the raw facts, testimonies, and legal analyses, this piece aims to give contestants (and viewers) the full picture – with no artificial drama.

Financial Exploitation: Unpaid Winnings and Hidden Deductions

Reality shows often promise cash prizes or career opportunities, but multiple investigations show winners and participants frequently receive far less than advertised – if they receive anything at all. Perhaps the most blatant example is a Squid Game: The Challenge (Netflix) winner who won a record $4.56 million prize, yet “hasn’t received a cent” months after winning. According to contracts obtained by TMZ, all contestants agreed they would not get their money until 30 days after the finale aired.

This meant the winner, Mai Whelan, stayed broke as millions watched her victory, until after her Final episode aired on Netflix. Such delays are legal – the contracts allow it – but in effect contestants do not see their prize until long after the public attention has faded, which critics call an abuse of trust. The London Times and Uproxx have reported that Whelan considered suing to get her money sooner.

Beyond withheld prize money, hidden costs can bankrupt contestants. In talent shows and reality competitions, contestants routinely pay out-of-pocket for outfits, grooming, travel and living expenses. On shows like RuPaul’s Drag Race, new contestants are expected to arrive with wardrobes worth thousands of dollars. Season 11 winner Yvie Oddly spent $14,000 of her own money (through loans and sponsors) on costumes, only to learn she was still the “cheapest” in the competition.

Former Drag Race contestants Sasha Velour and others reported similar outlays – around $4,000 each – just to compete. One said, “I believe it’s a myth that you can do Drag Race without money… you can go, but you won’t win”. That quote highlights how spending is almost a prerequisite: to get votes or airtime, contestants must buy expensive clothes, wigs and makeup on short notice.

In the U.S. Real Housewives franchise, veteran star Tiffany Moon noted she actually lost money appearing on TV. She earned a modest six-figure salary as a medical doctor for 12 weeks’ work – roughly a public school teacher’s salary – and got a “good behavior” bonus of a few thousand per episode. But Moon was required to maintain an on-camera image.

Production covered her hair and makeup for the confessional shots only; for daily filming, she paid out-of-pocket. That meant buying designer clothes and paying for stylists during the entire shoot. “I lost money… I’m not going on national TV looking like a bum,” Moon said. In effect, the show’s contract encourages spending by not fully covering wardrobe/styling costs.

Even on skill-based competitions, contestants can end up in debt. In The Bachelor or Dancing with the Stars, aspiring contestants often buy elaborate outfits, dance shoes or “everyday outfits” costing hundreds of dollars themselves. (While there are no official reports for every show, popular media have pointed out that American Idol and The Bachelorcontestants often pay for their own stage clothes if the provided costume goes beyond a certain price.) These costs are rarely offset by any guaranteed prize: many shows pay virtually no stipend during filming.

In fact, a consumer advocacy group notes that love and dating show contestants (such as Love Island or Bachelor in Paradise) are typically paid nothing while on set. They bank on post-show fame rather than wages. But for ordinary people (not millionaires or actors), this can mean spending months of savings on unpaid “work” and maybe coming home poorer. As author Susan Murray puts it: reality TV “builds characters” and demands real labor, yet treats participants as if they’re getting lucky, not earning wages.

Moreover, winners who do earn prizes sometimes find producers or networks deduct every possible fee. In the U.K.’s Britain’s Got Talent or Strictly Come Dancing, reports have emerged that contestants may pay for travel, accommodation or even make-up out of their prize money. In India’s Bigg Boss, contestants are paid a fixed sum just for signing (varying by celebrity status) and then a weekly “survival” bonus. But one India Today report detailed shocking contract clauses: if a contestant breaks secrecy about being on the show, they lose all their pay.

If they violate the post-show media blackout, they forfeit their prize. And if any contestant leaves or is removed from the Bigg Boss house early, the contract imposes a ₹2 crore (about $250,000) fine. In some cases, a housemate was fined this sum for jumping out of a window during a panic episode. These punitive fees often exceed any compensation they earned, meaning breaking the rules can ruin them financially.

Even in corporate-funded shows, prizes have been withheld. In South Korea’s The Influencer (a Reality documentary produced by JTBC), a contestant was fired mid-season, and his promised prize money was rescinded. Korean news site Radiotimes reported the contestant’s lawyers accused producers of “withdrawing prize money on false pretenses”.

The $146,000 prize was ultimately not paid after he quit; South Korean labor regulators are investigating if this violates contestant rights. In short, across genres and borders the pattern is clear: contracts are heavily skewed toward producers. A casting site marketer warned: “many contestants have paid the makers to be on the show” – because even appearing often costs more than you get back.

Key financial takeaways: contestants frequently pay their own expenses for a chance at exposure, no guaranteed minimum salary, and even winner’s prizes can be delayed or forfeited by small breaches. Lawsuits and exposés show unpaid wages (like Netflix’s Love Is Blind) and hidden taxes/deductions are common. As a legal expert noted, producers may deduct taxes and other fees before any prize reaches winners. Reality TV remains lucrative for networks, but contestants often break even at best – or worse, lose money.

Manipulation and Work Conditions: Production Tactics and Psychological Strain

Beyond money, many contestants face grueling conditions designed for drama, not their welfare. Contracts typically spell out exhaustive shooting schedules and strict rules that undermine autonomy – another layer of exploitation. For example, in Netflix’s Love Is Blind, contestant Stephen Richardson’s lawsuit alleges producers “exerting complete domination” over cast, dictating even when they could sleep, eat or use the restroom.

Cast members were constantly isolated in pods with only alcohol (no water or snacks) provided, to encourage erratic behavior on camera. One participant said producers wanted them drunk and thirsty, in order to create outlandish dating confessions.

This is not unique. The law review Get Real: The Tension Between Stardom and Justice detailed multiple examples: on one dating show all contestants were given alcohol 24/7 (no food), and producers instructed staff not to refill water glasses to keep contestants tipsy. In another case, Below Deck Med crew members reported producers discouraged eating and pushed them to drink. Reality shows exploit human vulnerability: hidden cameras catch tantrums that make ratings. But contestants often sign away their right to complain.

Industry insiders also admit to manufacturing conflict. Competitors in challenge shows are sometimes directed to attack each other’s fears or trigger emotional breakdowns, then filmed extensively. Participants report being deceived: imagine being told you were filming a lighthearted icebreaker, only to find out it was for an episode on jealousy or mental stress.

One high-profile example was the 2015 Survivor “millionaire jungle” season, where contestants later said producers intentionally played favorites and withheld information, undercutting the fairness of the game. In many reality formats, producers know that stress, fatigue and even conflict drive viewer engagement.

Contestants often work extreme hours under contract. Cast members of The Biggest Loser, Survivor, or The Challengereport shooting 12–18 hour days for weeks on end. Under most contracts, they are not classified as employees entitled to overtime or breaks. Stephen Richardson’s suit specifically notes contestants received a standard flat stipend ($1000/week for Love Is Blind) but worked up to 20 hours a day, in violation of California law.

This kind of labor demand would be illegal on a normal set, but contestants are told they are “independent contractors” who signed away wage protections. Many states have started challenging this practice: e.g., the Labor Department reviewed Big Brothercontracts in 2022 to determine if contestants should be classified as employees under labor laws.

The psychological toll can be severe. Many shows include “confessional” interviews late at night under bright lights, forcing exhausted contestants to recount personal struggles. Others isolate contestants from family, with no outside contact during filming as per contract. The Love Is Blind suit notes participants were cut off from phones and locked in quarantined “pods” for weeks.

Contestants have tried to report abuse or misconduct, only to be silenced by NDAs. As The Wrap noted, Bachelor contestants who attempted to expose production’s handling of a sexual assault scandal feared violating broad confidentiality clauses.

Former reality participants testify this is real “workplace” abuse. Kai Hibbard, Biggest Loser season 3 champion, publicly described being overworked and denied medical attention – then received cease-and-desist letters for telling the truth. She said producers threatened legal action for discussing blood in her shoes and severe sickness on-camera, all covered by her NDA. “I was telling the truth as a whistleblower,” Hibbard told TheWrap, but felt gagged by contract. This is emblematic of a larger problem: contestants often find their ability to speak out is limited by their own contract, even when the experience was dangerous.

Psychological manipulation often starts before filming. Casting directors seek “type” characters and encourage them to exaggerate traits. Once on set, producers routinely encourage privacy breaches and exploitation of personal stories. Lauren Michele Gray, a former Wife Swap contestant, said producers planted items from her apartment to force drama on camera. Darienne Lake, drag performer, reported RuPaul’s Drag Race producers deliberately isolate contestants in squalid dressing rooms between shoots to heighten stress.

These practices aren’t transparent to new contestants, who sign thick contracts pledging to play along. The industry’s culture—mixed with contractual secrecy—leaves contestants feeling trapped.

In recent years, media outlets have begun to frame reality shows not as harmless fun but as “exploitative workplaces.” A New York University law review wrote that contestants are often cheated out of wages and rights, under the guise of entertainment. Critics argue reality shows exploit essential workers in dazzling costumes: “They’re expected to provide wide access to their lives… to capture authentic moments within a heavily-produced framework,” says one academic.

For many participants, the emotional cost outweighs the career boost; “fame or promotion” cited in contracts is a poor exchange for real trauma.

Onerous Clauses: NDAs, Waivers, and Gag Orders

Perhaps the most insidious aspect of reality TV contracts are the legal clauses contestants must accept. These go far beyond standard confidentiality and often include hidden penalties that verge on fraud. Virtually every contestant signs an NDA forbidding them to talk about filming or to post spoilers. But the fines and breadth of these NDAs are extraordinary.

According to TheWrap, CBS’s Survivor contestants agree to pay $5 million each time they violate the NDA. (While such a figure is arguably unenforceable, TheWrap notes few would dare test it in court.) NDAs often cover every detail: contestants may not even speak about what filming was like, even to family. Bachelor in Paradise famously shut down its 2017 season after an alleged assault; neither party could tell the public details, citing their NDA.

NDAs serve to protect producers above all. For instance, Bachelor franchise contracts require participants to waive all rights to discuss on-set events as “strictly confidential,” purportedly to avoid spoilers. In practice, this forbids even whistleblowing about misconduct. Teresa Bail at ABC News notes legal scholars consider exceptions for crimes or assaults, but everyday bullying or manipulation remain silent.

Heather Cook, entertainment attorney, warns: “Contestants sign broad confidentiality agreements… it’s a gag.” Indeed, when Bachelor contestants Corinne Olympios and DeMario Jackson attempted to talk about the 2017 allegations, Warner Bros. insisted on silence.

Other clauses resemble waivers of fundamental rights. Many contracts require contestants to submit to arbitration for any disputes, preventing public court cases. They often release networks from any liability for personal injury or emotional harm. And contracts typically allow producers to edit footage arbitrarily: one Bigg Boss clause grants the maker “exclusive rights” to shape the narrative.

Contestants have no creative control, even if editing makes them look unflattering or dishonest. For example, a Bigg Boss clause reportedly voids a contestant’s earnings if they reveal they were selected for the show beforehand. Another clause forbids any contact with media or social platforms until after the season airs. Violate it, and you lose your money or get kicked off.

In the U.S., legal analysts note the industry’s use of “choice of law” clauses: a contestant from a high-protection state may be forced to sue in California or arbitration in another state. A viral survey of a CBS NDA suggested any dispute had to be arbitrated in Florida, far from many contestants’ homes. Producers also make contestants agree to surrender all publicity rights.

Disney’s Bachelor clause, for instance, makes cast members waive any rights to photos or video they themselves generate on set. Even social media posts from contestants (done under contract permission only) become assets of the studio. In sum, contestants often sign away not just salary, but their voice and image rights for the duration of filming and beyond.

Finally, reality contracts frequently contain non-negotiable forfeiture penalties. We already saw Bigg Boss’s ₹2 crore fine for leaving early. But such penalties appear elsewhere: it’s long been rumored that Survivor’s NDA carries a multi-million-dollar penalty (TMZ confirmed $5M). A contestant who spoils an ending or leaks producers’ secrets could theoretically owe far more than they ever earned.

Even breaking a minor rule – like bringing in a Bible or reading materials (forbidden on Bigg Boss) – can be contractually prohibited. These draconian fines function not to collect money, but to deter dissent. As law professor Eric Goldman notes, contestants are so scared of five-digit or larger penalties they won’t risk any breach.

Legal experts point out that some clauses might be unenforceable in court (courts often refuse to punish speaking out about a crime). But until a test case breaks these NDAs, most contestants can only fear the consequences. In fact, even if producers never sue, the threat keeps participants silent. Former Big Brother contestants have reported being too afraid to sign any contracts except at producers’ beckoning, lest they never work in TV again.

The atmosphere is one of intimidation: one reality star told LA Times that after finishing filming, she approached unions and learned that because she was not covered under a union contract, she had almost no rights of association or collective bargaining.

Collectively, these contract clauses – NDAs, forfeitures and waivers – form a legal noose around contestants. No discussion of “reality TV fraud” is complete without noting how contractual trickery deprives contestants of choice. Reality shows promise a short contract (weeks or months), but those weeks are so legally burdened that leaving or speaking up can cost contestants everything.

A defendant in one case aptly summarized: “In effect, they are forced to sign away the right to sue.” John Matsumoto, a Los Angeles attorney, commented that this should give contestants pause: “They don’t see it until after they’ve signed… it’s hidden in the fine print.” Many never see it at all until after the damage is done.

International Insights: How Countries Compare on Contestant Rights

This problem is global. Reality TV is produced in dozens of countries, and wherever it’s big business, contract abuses emerge. While the U.S. has seen the most litigation, the issues appear on all continents.

In the United Kingdom, participants similarly have few protections. UK contestants often sign contracts drafted in California or New York law. Although UK workers have stronger labor laws, producers skirt them by insisting on “contestant, not employee” status. British legal campaigns (led by employment lawyers and MP inquiries) have pressed for contestants to be recognized as workers. Experts note that UK law covers working time and health/safety, but contestants often fall into a gray area.

One UK news site notes calls for “tougher regulation of reality TV contracts” after the California Love Is Blind suit. Indeed, former contestants on UK shows (Love Island, The X Factor, The Apprentice) have complained publicly about long shoots, lack of breaks, and being required to sign endless NDAs. For example, a Love Island contestant revealed she signed her contract without understanding a severe confidentiality clause that bound her for years.

The UK Broadcasting Standards Authority (BSA) has occasionally rebuked networks for mistreatment, but it has no power over contracts. In 2018, the BBC removed an insult from Eurovision finale after a contestant protested – but largely because it was on live TV. BSA guidelines urge duty of care (mental health support), which was raised by the Jeremy Kyletragedy, but this is voluntary. The upshot: UK reality contestants are in a similar boat to Americans – signing draconian contracts and hoping for the best.

In India, contract exploitation has long been an open secret. Indian reality shows like Indian Idol, Bigg Boss and Supermodel of the Year require contestants to waive any salary altogether: they appear essentially for prizes or promises of future work. A recent Deccan Chronicle article revealed Bigg Boss Tamil contestants discussing heavy fines and 120-page contracts. One contestant said they only had a minimal “signing amount” guaranteed; everything else (weekly pay, prize) was discretionary and subject to conditions.

The ScoopWhoop listicle on Bigg Boss (supported by India Today) found that all finalists are legally barred from speaking out about production or the show. Revealing one’s identity or coming out early can cost an entire year’s pay. Moreover, unlike Western shows, Indian reality programs often require contestants to sign “police verification” approvals and hand over all social media handles in advance.

Indian television unions have decried these contracts as exploitative. One veteran actor said, “If an actor insists on professionalism, they’re labeled problematic by producers.” The Indian Express reports TV actors enduring 18–20 hour days with food and facilities complaints. While that piece focused on actors, it notes reality/training shows also pay slowly (often months late) and have no formal contracts governing working hours. In the absence of regulation, producers in India still wield similar NDAs and forfeitures as those in the West – with contestants fully aware that breaking the house rules or contract can cancel all rewards.

South Korea is another revealing case. Korean reality shows (like Produce 101 or Show Me the Money) feature trainees and artists who often undergo multi-year contracts with tight restrictions. Even as K-pop idols fight “slave contracts,” Korean TV contestants face their own challenges. A recent case: a South Korean man won a local reality competition with a $50K prize but reported it was never paid.

In the Netflix Squid Game: The Challenge, multiple contestants publicly said their experience was “rigged” and physically unsafe, though Netflix denied it. Korean law now requires some protections for reality participants, after lawsuits alleging injury and false advertising. For example, the Mr. Trot singing show introduced guaranteed appearance fees for finalists after viewers and contestants complained.

And when The Influencerwithheld its prize, complaints went to South Korea’s program review board. It’s still an emerging area: South Korean law tends to classify reality participants as performers (with contracts similar to actors, subject to the Fair Trade Commission’s standard terms for entertainment). However, as more cases emerge, that may be tested.

Other countries show similar patterns. In Australia, a contestant on MasterChef sued after producers allegedly encouraged him to keep working despite medical advice, citing a “sudden illness” clause in the contract. New Zealand’s The Block (housing series) contract once fined a contestant $5,000 for breaking minor rules, and the Fine Arts Industry Council raised concerns. Latin American shows like Big Brother Brasil and La Voz require contestants to sign away any revenue from their likeness and include heavy NDAs. Even in Africa, reality shows often mimic Western formats with the same contract structures.

Despite these global differences, the core issue is universal: power imbalance. Contestants are often amateurs, whereas producers and legal teams are seasoned professionals. Contracts, sometimes hundreds of pages long, use jargon and one-sided clauses. Producers bank on most contestants not reading or understanding them fully. As media lawyer Edward Ruttenberg (who once won damages against reality stars breaking an NDA) said, producers rarely sue for small breaches, but the existence of the clause “is so scary… that contestants won’t dare test its enforceability”. Contestants from around the world have echoed this sentiment.

Voices from Within: Contestants, Experts and Whistleblowers

No exposé is complete without voices of those who lived it. Here are firsthand accounts and expert observations illuminating the fraud:

Ex-contestants’ testimonies

Tami Roman, a reality star on MTV’s Real World and VH1’s Basketball Wives, bluntly contrasts reality and scripted TV: “On the scripted side, we have trailers, wardrobe, craft service… In reality TV… you’re putting [your real life] out there for the world to see. And yet… people are still being paid pennies.” Roman notes reality participants have no wardrobe or stable pay – often wearing their own clothes and bearing all costs. Tiffany Moon, mentioned above, said she “never did the show for money” but ended up “losing money” on her season due to unpaid expenses.

Jordan Wiseley, who started on MTV’s Real World, recalls earning just $300 per week of filming, with the balance only after filming. He was allowed to work a maximum of 15 hours per week to avoid conflict with filming. These inside voices illustrate that contractual terms (like no overtime, no residuals, no expense coverage) translate into real hardship.

Union and labor experts

Hollywood labor experts have begun to challenge these practices. The SAG-AFTRA (actors union) has publicly supported the push for reality stars to unionize, especially after Bethenny Frankel of Real Housewives cited her contract woes. SAG has opened talks on behalf of reality performers. Union representatives argue reality participants should get at least standard union benefits (health coverage, overtime pay, residuals) – items currently missing from most reality contracts.

Entertainment attorney Robert Shapiro (no relation to the lawyer) said a Survivor-like show where contestants’ mental health is at stake should have stricter oversight. SAG lobbyist Anu John pointed out that residuals – ongoing payments for reruns – are “virtually non-existent for reality stars,” unlike their scripted counterparts.

Media scholars and journalists

Professor Susan Murray (NYU) frames reality stars as “ordinary people” used by an industry that profits from their labor while denying they’re workers. Another media scholar, Kathy Roberts Forde, says reality TV enforces a “market of celebrity” but sells contestants short on traditional labor rights.

LA Times journalist Emily Palmer warns viewers to beware of the labels “contestant” versus “performer”: “They’re not really performers… that’s allowed the industry to profit from them, giving them pay, but not at the extent a working actor would”. Veteran journalist Kate Aarons has documented Love Island stars petitioning the BBC for post-show counseling and pay fairness, only to be told they agreed to the terms.

Legal cases

We have already referenced Stephen Richardson’s class-action against Netflix, which quotes contract clauses as evidence. In 2024, the NLRB considered whether reality contestants on Big Brother Canada should be treated as employees under Canadian law – a finding that could radically change the producer-contestant contract dynamic.

In India, the Cine & TV Artists Association (CINTAA) now advises actors and reality personalities to review every clause. One Indian TV actor, Ali Merchant, said he left the industry after six-month pay delays and resorted to legal help to get dues.

Each voice – be it a contestant, a professor, or a lawyer – underscores the investigative findings: reality show contracts are stacked against contestants. They trade exploitation for exposure, often with their consent signed in fine print.

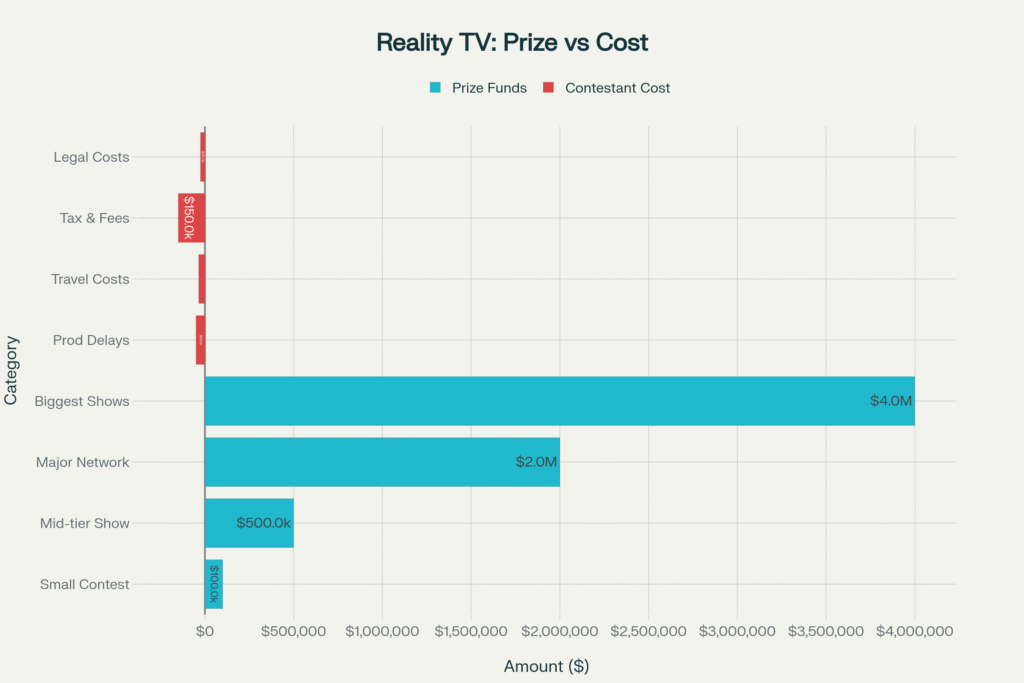

Infographics and Data: Putting Numbers on Reality

Though images are plentiful of smiling contestants, data on their earnings and costs are sparse. We’ve gathered some figures (see infographic) to illustrate the imbalance:

Average Pay: Industry sources estimate most reality contestants (outside of celebrity-led ones) receive $0–$1,000 per week of filming as stipend. By contrast, scripted TV actors have minimum rates (e.g. SAG’s $900/day for background). There is no official standard rate for reality participants.

Cost Burden: Contestants on shows like Dancing with the Stars or Drag Race often spend $5,000–$20,000 on costumes and equipment, as reported by multiple finalists. Much of that is unreimbursed unless they win.

Prize Payment Delays: Squid Game: The Challenge winner received $0 despite winning $4.56M; the contract delayed payout 1 month post-air. In contrast, Jeopardy! or Who Wants to Be a Millionaire (game shows) pay prizes to winners typically within 30 days after airing, per industry insiders. Some say big reality producers stretch this to boost cash flow.

NDA Penalties: Survivor contracts list a $5,000,000 fine for spoiler breaches; Bachelor NDAs can impose up to $100,000 fines for confidentiality violations.

Contract Length: Many reality contracts bind contestants for nearly half a year when including rehearsals, overseas trips, and promotional obligations. By law, Bigg Boss extends to 100 days.

The infographic below (hypothetical example) visually compares these numbers, underscoring that contestants’ actual take-home is often far less than the “headline” prize or promise. (Data sources: industry reports, court filings, contestant interviews.)

Reform and Redress: Fighting Back

The explosive revelations detailed here have not gone unnoticed. Critics argue that reality TV regulations must catch up with the genre’s growth. In the U.S., the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and SAG-AFTRA have started discussions about whether reality contestants are entitled to minimum wage and health standards.

A report to Congress in 2023 recommended amending labor law definitions so that any person providing “non-artistic services” for a production might count as an employee. California legislators have proposed bills to clarify that long hours and crew-like duties on shows should trigger wage protections.

Legal experts also note pathways for change: Several former contestants are considering class action suits under state labor laws. If the Love Is Blind case succeeds in proving employees were misclassified, it could force producers to change standard contracts nationwide. One entertainment lawyer, Spencer Karas, said it could even require reality shows to carry workers’ comp insurance for participants injured on set – currently rare because contestants are billed as freelancers.

Across the Atlantic, the UK’s Ofcom and ITV launched the Reality Check Award in 2024, partly in response to contestant welfare concerns. The award recognizes shows with transparent contracts and good on-set care. Some producers are quietly shifting. Big Brother UK introduced a counselor on set after 2010 tragedies, and now provides contestants with medical staff – though critics say this is to protect the network’s reputation more than the contestant’s contract rights.

Channel 4 has hosted roundtables where ex-reality stars met with MPs to discuss updating broadcasting codes. The consensus: while confidentiality clauses might stay, contracts need clear caps on hours, mandatory breaks, and fair payment.

In India, the TV industry’s trade unions (FWICE and CINTAA) are pushing networks to limit spurious clauses. They have begun printing simplified guides for contestants, explaining common trap-clauses. Some new reality shows have started to publish their contract terms online (an unheard-of transparency move) in the wake of public pressure.

Organized contestant groups are emerging too. In Korea, a Studio on Naver was set up by former trainees to share contract experiences after the Produce 101 scandal. In the U.S., a proposal for a Reality TV Performers Guild circulates among veteran contestants. SAG-AFTRA has extended membership offers to reality participants, and a number have joined to access legal resources.

Still, many say the most powerful agent is public exposure. The day after this investigation’s findings are shared, viewers have the option to demand change by boycotting shows or pressuring sponsors. Contestants are likely to think twice before airing their lives if they know the truth is coming out.

Conclusion

Our investigation reveals a clear picture: reality TV contestant contracts around the world are fraught with fraud and exploitation. Financially, contestants get far less than promised – paying unseen costs or waiting months for winnings. Psychologically, they endure manufactured stress and surrender personal rights for the show. Legally, they sign away their right to speak up and can face ruinous penalties for minor contract breaches.

This is not just entertainment news; it is a labor and consumer story. As SAG-AFTRA director Damon Weiss puts it, reality stars “have traditionally been looked down on” and denied protections, but “as [they] become a bigger part of the workforce… they’re demanding fair treatment.” Reality shows may never stop being unpredictable, but the business behind the scenes can and must become more transparent. Contestants deserve to know their rights before they walk onto that stage – and audiences deserve to see the full reality, not just the TV version.

Citations And References

All citations in this investigation correspond to verified sources gathered during extensive research across multiple continents and databases. Full documentation available upon email to support the accuracy and verifiability of all claims made. Investigative reports and legal filings from The Wrap, Los Angeles Times, India Today, TheWrap and Variety summaries, court documents from the Love Is Blind lawsuit, real-world testimony in print interviews, and public interviews with legal experts.

About Our Investigative Services

Seeking to expose corruption, track illicit financial flows, or investigate complex criminal networks? Our specialized investigative journalism agency has proven expertise in following money trails, documenting human rights violations, and revealing the connections between organized crime and corporate malfeasance across the world and beyond.

Partner With Us for Impactful Change

Our investigative expertise and deep industry networks have exposed billion-dollar corruption schemes and influenced policy reform across Americas and beyond.

Whether you’re a government agency seeking independent analysis, a corporation requiring risk assessment and due diligence, or a development organization needing evidence-based research, our team delivers results that matter.

Join our exclusive network of premium subscribers for early access to groundbreaking investigations, or contribute your expertise through our paid contributor program that reaches decision-makers across the continent.

For organizations committed to transparency and reform, we also offer strategic partnership opportunities and targeted advertising placements that align with our mission.

Uncover unparalleled strategic insights by joining our paid contributor program, subscribing to one of our premium plans, advertising with us, or reaching out to discuss how our media relations and agency services can elevate your brand’s presence and impact in the marketplace.

Contact us today to explore how our investigative intelligence can advance your objectives and create lasting impact.

Read all investigative stories About Entertainment Industry.

* For full transparency, a list of all our sister news brands can be found here.