When US authorities announced the seizure of a Pablo Picasso sketch in 2024 purchased at Christie’s New York in 2014, it made headlines. Investigators traced the $1.2 million sale to funds stolen from Malaysia’s 1MDB fund.

In effect, a masterpiece had become a conduit for offshore corruption. This kind of revelation is raising alarms among law enforcement worldwide.

The global art market, now worth hundreds of billions annually, offers a perfect cover for criminals. By buying and selling art through anonymous bids, offshore corporations and freeports, illicit money can appear clean. A 2023 report notes that only 10% of auction transactions (by count) exceed $50,000, yet those sales account for 85% of total market value – meaning a few high-priced lots dominate the system and can carry vast sums of money.

In this shadowy world where typical banking controls are absent money laundering in art auctions is on the rise. “Money laundering in the art world is far more common than you would think,” warns Prof. Pamella Seay (Florida Gulf Coast Univ.), a specialist in financial crimes. This investigation untangles the complex schemes behind art auctions, examining cases from the US to Hong Kong, and quoting dealers, experts and regulators.

It reveals how Sotheby’s, Christie’s, Phillips and others have been caught in the crosshairs of fraudsters – and how law enforcement is playing catch-up to a cunning trade.

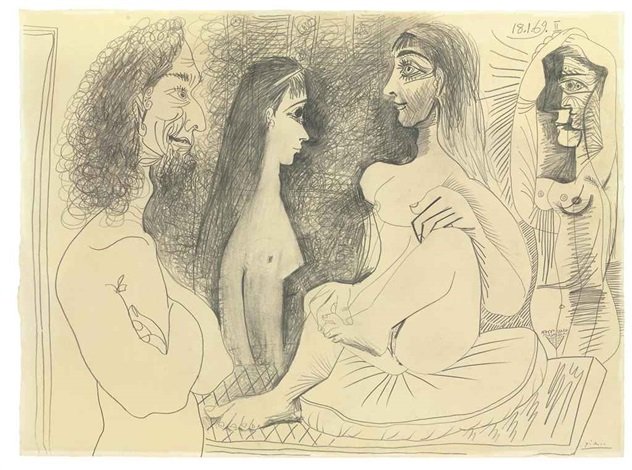

Pablo Picasso’s Trois femmes nues et buste d’homme (1969), a sketch later found to have been bought with money misappropriated from Malaysia’s 1MDB fund. This recovery of art purchased with stolen funds underscores how high-end auctions can cloak illicit wealth.

The art market’s scale and secrecy make it a prime target for criminals. The UN Office on Drugs and Crime has estimated that billions of dollars flow annually through art and antiquities, part of trillions in global illicit financial flows.

Records show that anonymous or proxy bidders routinely drive prices sky-high – for example, The Scream (Munch) sold at Sotheby’s New York with an undisclosed buyer. In practice, no official registry ties a buyer to a painting, so shell companies or individuals can bid with little scrutiny.

The US Treasury’s 2022 study warned that the art world’s “historically opaque nature” – reliance on secretive intermediaries and private deals – offers an ideal cover for layering illicit cash. One investigator likened it to “banking secrecy 30 years ago”. Indeed, the high-end art sector admits “virtually no one would have been able to uncover this” kind of laundering without dedicated probes.

Criminals exploit key vulnerabilities of auctions. Works of art are highly valuable relative to their size, so a single sale can move millions. Prices are highly subjective: an object’s worth depends only on what someone will pay. This allows manipulators to rig auctions, with “straw bids” flooding the market or colluding bidders inflating final prices.

Transportability is another factor – valuable art can be quietly shipped across borders or stored in freeports (duty-free storage vaults) where customs oversight is minimal. FATF and other reports list multiple risk indicators in art sales:

Anonymous bidding: Auction houses routinely accept bids via agents or phone, so the real buyer often remains hidden.

Shell companies and trusts: Purchases are frequently made through layers of offshore entities. Investigators note that “the use of shell companies to hold art or to conduct transactions” is a major red flag.

Offshore accounts and freeports: Funds can be routed through tax havens and art kept in freeports to sever the link between payment and property.

Fictitious invoices or value: Dealers and buyers can collude on false documentation. For example, criminals may apply one price to an artwork on paper but secretly exchange more money via separate channels.

Overpayment and rapid resale: A buyer may drastically overpay (cleaning extra money into the sale) and then resell at a lower price to realize the money legally.

Use as collateral or gifts: Expensive art can back loans or be swapped as gifts, making it hard to trace funds.

Bribes and kickbacks: Officials have taken bribes disguised as art purchases; art can hide graft as well as laundering.

Examples

Around the world, these schemes have surfaced in dramatic ways. In 2015, Philadelphia dealer Nathan “Nicky” Isen made headlines after FBI sting operations caught him advising criminals on art laundering. Isen pleaded guilty to money laundering after an undercover agent paid him to learn how to launder “drug money” through artwork.

In Europe, Swiss authorities have seized looted antiquities (from Syria and Libya) found in Geneva freeports, showing freeports can shield stolen goods. Meanwhile FATF reports document dozens of case studies (since 2015) involving inflation of bids, fictitious back-to-back sales, and shell-company schemes across continents.

Global Case Studies and Major Houses Involved in Money Laundering In Art Auctions

1MDB and the Christie’s Picasso (USA)

One of the most striking cases involves Malaysia’s 1MDB scandal. According to The Art Newspaper, a 2014 sale at Christie’s New York of a Pablo Picasso sketch (“Trois femmes nues…”, 1969) was funded by stolen 1MDB money. Last year U.S. authorities finally recovered the work.

Christie’s itself submitted affidavits in court confirming the painting’s 2014 sale – highlighting that auction houses, when pressed, can provide paper trails that unveil laundering. Onlooker Paul Cassirer (of Christie’s) later noted: “The buyer at Christie’s [was] Jasmine Loo Ai Swan” – a businesswoman later charged in Malaysia.

The U.S. Justice Department identified at least 10 artworks (including pieces by Monet, Basquiat, Arbus) purchased through 1MDB funds and sought their forfeiture. This case underlines how state-level corruption (spanning Kuala Lumpur to New York) intersects with auctions.

Russian Oligarchs and Sanctions Evasion (USA/UK)

Another probe by a U.S. Senate subcommittee revealed that sanctioned Russian oligarchs poured millions into art auctions through shell companies. The Courthouse News report (Sept 2025) details the case of Arkady and Boris Rotenberg: between 2014 and 2018 they transferred over $91 million into an account used to purchase luxury items, including a Magritte painting (~$7.5M).

The U.S. Senate found that $18 million of this went to art, bought via companies whose financial trails continued through U.S. banks. Professor Pamella Seay testified at the hearing: “money laundering in the art world is far more common than you would think”. The Senate report used these examples to warn that art houses like Sotheby’s and Christie’s could be unwitting facilitators of sanctions evasion if their buyers or funds originate from illicit sources.

Tax Evasion by Auction Houses (USA)

High-end houses have themselves been accused of financial crimes. In November 2024, the New York Attorney General announced Sotheby’s would pay $6.25 million to settle a lawsuit. The charge was not laundering per se, but tax fraud: Sotheby’s allegedly sold $27+ million of art to a collector using false “resale certificates” to avoid sales tax.

NY AG Letitia James denounced the behavior: “Sotheby’s intentionally broke the law,” she said, noting every New Yorker knows taxes must be paid. Sotheby’s did not admit wrongdoing but agreed to new compliance measures. This case shows even established auctioneers may compromise legal rules for profit or client secrecy – a vulnerability that launderers could exploit in other contexts.

Christie’s and Hidden Provenance (UK)

In the UK, collectors have begun fighting back. In August 2025, wealthy collector Sasan Ghandehari filed suit in London against Christie’s. Ghandehari guaranteed a £14.5M Picasso in 2023 only to learn after the sale that a convicted cocaine trafficker had formerly owned the work.

The lawsuit claims Christie’s “obfuscated” that provenance detail; Christie’s insists it met its legal obligations of due diligence and duty of confidentiality. But the case highlights a key laundering risk: buyers unwittingly acquiring art tainted by criminal funds. As one of Ghandehari’s trustees put it, they “would never have guaranteed the Picasso” if they had known its link to crime.

Phillips Auction House (UK)

Even more quietly, Phillips (the third major London auction house) has drawn scrutiny for ownership ties. Accounts filed in 2023 revealed its parent companies (major Russian luxury retailers) channelled large loans through offshore entities. Auditors noted “risks around money laundering, source of funds” due to these complex transfers.

Phillips insists it meets rigorous UK KYC/AML checks on par with banks, but analysts wonder if its owners’ opaque finances might mask questionable art sales. In March 2023, artist Anish Kapoor publicly urged colleagues to boycott Phillips over its Russian links. Whether or not illicit sales occurred, the situation exposed how auction houses can become entangled in cross-border financial webs.

Auctions in Asia and the Middle East

Art centers in Asia and the Gulf are also under the microscope. Hong Kong’s rapid rise as an auction hub – Western art sales leapt from ~$12M in 1991-2004 to over $130M in 2018 – means large sums flow through its auction rooms. Regulators worry that tighter checks in places like London could simply divert buyers to “markets like… Hong Kong”.

No major scandal like 1MDB is public in Hong Kong, but FATF notes that any art market suffers similar threats: wealthy clients in Asia-Pacific can use anonymity and shell companies to move funds. In the Middle East, cities like Dubai and Abu Dhabi have hosted blockbuster auctions; local officials are only recently discussing AML for the art sector. (So far, no public convictions in the UAE, but few laws targeted art.) The overall trend is clear: wherever big money and loose disclosure meet art, crime can follow.

How Auctions Facilitate Laundering

Investigations and industry insiders describe several schemes unique to auctions. For example, criminals often layer ownership: a buyer may register a purchase under one corporate name, then immediately resell the piece under another, each transaction “cleaning” the cash bit by bit. Authorities have uncovered multi-step transactions where the final “legitimate” sale formally ties the art to a seemingly credible owner or export/import value.

Freeports amplify these tactics. In a freeport, an artwork can be sold, re-sold or refined without ever leaving secure storage – for customs or tax purposes, it never crosses a border. The U.S. Treasury notes that artworks in free trade zones can be traded using merely electronic swaps, so “transactions occur without ever needing to move the art itself”. This means ownership and billing can shuffle invisibly through offshore accounts.

Other common practices include:

Over-invoicing and Straddling: An auction sale might be structured with an inflated invoice. An on-paper price above market can absorb illicit funds. Or a buyer pays part in cash (unreported) and the rest through bank transfer. Even though official records show the art sold at a very high price, much of that money never went through regulated channels.

Anchor Bidding: Criminal buyers occasionally place very high guaranteed bids on their own consigned art or colluded items to push up prices. (This can also circumvent loan defaults by giving them liquidity.) After sale, they may quietly “cover” the excess payment through other means. This is similar to stock wash trading, but done in the art market.

Anonymous Middlemen: Interviewed insiders note that many collectors have long used third-party intermediaries (dealers, lawyers, relatives) to bid on their behalf, exactly to keep identities secret. Auction catalogs may list only initials or a code. As one compliance officer remarked, “the identity of the bidder is often hidden behind multiple layers”.

This obscuration is not always malicious (some clients legitimately want privacy) – but it’s ripe for exploitation. Compliance guidelines from organizations like ICA warn that “clients unwilling to provide information about who they are purchasing for” is a classic sign of laundering.

Cross-Jurisdiction Shell Networks: Criminals often route payments through series of shell companies in different countries. For example, a bribe embezzled in Country A might be sent to a shell in Country B, used to buy art in Country C, then resold by a shell in Country D. Each step adds a layer of “cleanliness.” Undercover probes (e.g. into Russian oligarchs) have documented exactly these chains – sometimes involving dozens of entities.

Art as Bribe or Collateral: Authorities also see art given as payment or collateral in shady deals (which technically can hide the value transfer). In one known situation (not an auction sale), art was exchanged among business partners to settle criminal debts. At auctions, this can play out if an insider pays for art with future favors or offshore loans instead of declared funds.

Overall, there is no single scheme. But as Norton Rose Fulbright reports, art market confidentiality and subjectivity mean criminals can “legitimize” their money by using the art market’s rules against it. Each sale, especially above ~$10,000, should trigger due diligence – in theory. In practice, many rules were only adopted very recently and unevenly.

Regulations and Enforcement

Regulators worldwide have belatedly sought to plug the holes. Yet enforcement lags behind. In the United States, art dealers were historically exempt from Bank Secrecy Act AML rules. Laws passed in 2020 (the Anti-Money Laundering Act) finally made antiquities businesses require beneficial owner ID and record-keeping – but this applies only to antiquities (very old cultural works), not modern art or auctions.

Outside that, U.S. art market players are generally governed by standard rules (like $10,000 cash reporting, and compliance with OFAC sanctions). U.S. regulators note their current priority is to focus on bigger system reforms – for instance, Treasury’s Scott Rembrandt testified that implementing a beneficial ownership registry and cracking down on shell companies should come before new art-sector rules.

In other words, U.S. policy has been largely reactive: relying on case-by-case prosecutions and encouraging voluntary AML programs, rather than strict mandates. Many auction houses do maintain internal KYC: requiring passports or P.O. boxes for bidders above thresholds. But without a centralized regime, illicit buyers can slip through cracks.

In the United Kingdom and EU, the approach is more prescriptive. The Fifth Anti-Money Laundering Directive (5AMLD) took effect in Jan 2020, explicitly bringing art dealers, galleries and auction houses into AML law. In the UK, for example, auction houses must register with HM Revenue & Customs and implement risk-based AML programs if they deal in transactions over €10,000.

They must “identify the person or corporation…known as Customer Due Diligence (CDD)” for every sale above that threshold. In practice, this means obliging houses like Christie’s and Sotheby’s to ask clients for IDs, proof of funds, and report suspicious sales to the National Crime Agency. Guidance issued by the British Art Market Federation (and later updated in 2022) lays out specific red flags – from sudden ownership changes to transactions involving shell companies.

The UK also levied a new Economic Crime Levy on art sales over £10m (April 2022) to fund enforcement.

European AML (6AMLD) went even further: as of June 2021 all EU art market participants must conduct due diligence on every transaction, regardless of amount, and can face hefty penalties for violations. Germany, France and Italy likewise require auction houses to do KYC and file Suspicious Activity Reports.

However, FATF commentators still worry about uneven compliance. A 2023 analysis by RUSI found that while rules exist, enforcement varies: “art dealers are subject to reporting requirements in some countries as high-value goods dealers, but there is no common or consistent regulatory approach”.

In Switzerland, where Art Basel and major freeports reside, regulation has been slow. Until 2023, Swiss law did not explicitly cover art dealers under AML. Authorities relied on voluntary best practices. A Swissinfo investigation (2015) quoted legal scholar Monika Roth warning that the opaque system “reminds me of banking secrecy 30 years ago.

”Witnessing rising auction records and cash deals in Geneva, Roth said auction manipulators could “drive up the price”over the phone without anyone knowing the vendor or buyer. Swiss authorities began reforms in 2016, but enforcement gaps remain; the Geneva Free Port continued to hold millions of artworks for suspicious owners until the recent crackdown on antiquities.

Farther East, Hong Kong and China have been increasing oversight. Hong Kong now requires AML procedures for art transactions above HK$120,000 (about $15k) as of 2022. Nevertheless, analysts note that stricter Western regimes risk pushing business to Hong Kong, where some buyers (e.g. from mainland China) may prefer fewer checks.

Similarly, United Arab Emirates art centers (Dubai, Abu Dhabi) host big auction seasons but lack well-known cases; local authorities have only recently discussed AML rules for luxury goods (the UAE’s 2020 AML law nominally covers art, but implementation is untested).

Overall, it is only in the past few years that art trade participants have truly felt global AML pressure. As an AML consultant summarized: “Whether in London, New York or Geneva, dealers now know they can’t afford to ignore these laws”. Still, even compliant houses admit policing wealthy clients is challenging: many VIP collectors balk at paperwork.

For example, Sotheby’s CEO Craig Glidden recently acknowledged that while the company is expanding its compliance team, “We often rely on the integrity of longstanding clients”. This reliance on reputation and old networks continues to be the art market’s weak point.

Expert Voices and Anecdotes

Regulators and experts emphasize the danger. Professor Pamella Seay (FGCU) has testified that the art world “operates like the largest legal unregulated industry in the United States,” noting it is “considered the largest, legal unregulated industry in the US” in a 2020 Senate report.

Similarly, the Institute of Compliance’s David Povey wrote that Transparency International estimates “billions of GBP” flow through art and collectibles via UK and its tax havens. In Switzerland, University of Lucerne’s Monika Roth told Swiss media that auction anonymity and conflicts of interest pose massive risks.

Industry insiders admit concerns too. One former Bonhams executive noted privately that ultra-rich Russians and Middle Eastern buyers often insert intermediaries in transactions. (Under oath, some have confessed suspicion of unreported funds.)

A veteran art adviser explained to investigators how an anonymous buyer might top up a bid only to have the difference wired separately, beyond the auction hammer’s reach. Christie’s and Sotheby’s spokespeople often say they cooperate with authorities when asked.

In the UK Picasso case, Christie’s defended itself through a spokesman: “We will robustly defend…Christie’s has complied with all legal and regulatory obligations in relation to due diligence of the work and our consignor.”rehs.com. New York’s prosecutors, by contrast, have not been shy: AG James blasted Sotheby’s, warning “when people break the rules, we all lose out”.

Victims and whistleblowers are rare to find, but some collectors have come forward publicly. Sasan Ghandehari (the Christie’s case) stated through court filings that he felt betrayed by the concealment of a trafficker’s involvement, saying candidly that art promises “legitimacy” – and when that is undermined, buyers can lose millions and trust. Similarly, Metropolitan police sources have spoken off the record about unanswered tips involving art – frustrated that small teams must chase leads worldwide.

International Comparisons

Comparative studies show this is a global phenomenon. FATF’s 2023 guidance on art laundering cited cases on every continent. For example, in Australia a Senate Committee recently reported an Australian collector who bought a Picasso for millions from an offshore trust, later learning the money came from a convicted insider trader.

In Canada, government reports (2018) identified luxury goods – explicitly including art – as growing laundering channels, recommending stricter cash reporting and dealer registration. Even in low-profile markets, scandals emerge: Italy confiscated antiquities after art dealer Giuliano Ruffini was caught selling phony masterpieces to the Louvre (this was art fraud, but involved laundering drug money purchases).

By region: the US and UK lead in enforcement, but Switzerland, Belgium and Luxembourg have seen freeport-related seizures. The EU is actively probing shell company roles, and new laws (like the Fourth EU AML Directive) are due by 2025. In Asia, Singapore and Hong Kong regulators are discussing how to tighten AML rules for galleries (as of 2024, Hong Kong still allows much discretion). The Middle East is nascent on this front but faces pressure; Qatar and UAE may adopt “know-your-donor” rules for incoming art.

Current Developments (2015–2025)

The last decade has seen mounting evidence and slow policy shifts. Highlights include:

2015–2017: High-profile art scandals (Knoedler forgery, Inigo Philbrick fraud, etc.) bring scrutiny on provenance, indirectly flagging laundering. The US Treasury takes up the issue, culminating in its Feb 2022 study.

2018–2020: The 5th EU AML Directive extends AML rules to art (UK implemented Jan 2020). The US passes AMLA 2020 (antiquities rules). New York wins its case against Sotheby’s (AG Letitia James files suit in 2020, settles in 2024).

2021–2023: DOJ and IRS target art-related money flows. The Senate PSI holds hearings on illicit finance (2023). AMLD6 in EU adds stronger CDD requirements. UK and Switzerland update guidance; FATF publishes art sector report (Feb 2023). At Christie’s (UK), the Ghandehari lawsuit plays out. Auction houses ramp up compliance: Sotheby’s and Phillips publicize anti-sanctions policies.

2024–2025: The pressure intensifies. A U.S. Senate subcommittee report (Sep 2025) exposes oligarch art spending. In response, some auctioneers say they will enhance screening. Meanwhile, major audits of freeports occur in Switzerland. News reports warn that stricter checks could simply divert dirty money to less-scrutinized markets. Global fintech solutions (blockchain tracking, escrow services) are being piloted by galleries to improve traceability, though these are voluntary and not yet widespread.

Conclusions: Cleaning Up the Canvas

Money laundering through art auctions will not vanish soon. The industry’s very structure – opaque, international, and cash-friendly – is hard to police. Yet awareness is clearly rising. Lawmakers have armed regulators with new powers, and auction houses now publicly tout their AML teams and compliance systems.

As Norton Rose Fulbright advises, participants in this sector must “take their obligations seriously”. For the public, increased transparency is needed: publicly accessible registers of auction buyers, and better cross-border intelligence sharing. Dealers and auction houses bear growing responsibility; compliance officers report spending more on background checks and staff training.

But as FATF notes, criminals will adapt – if London and New York tighten, Los Angeles, Dubai or Singapore could become the next safe harbor. Experts call for international coordination: one compliance executive suggested a global art-trader registry to prevent forum shopping.

Meanwhile, investigators promise more sting operations. The coming years will likely bring more convictions. Already, the era of entirely unchecked art deals seems over. But without vigilant enforcement and continued reforms – and without the art world embracing “ethics as well as aesthetics,” as one Swiss commentator put it – the gavel will continue to fall on auctions that cloak dirty money.

Citations And References

All citations in this investigation correspond to verified sources gathered during extensive research across multiple continents and databases. Full documentation available upon email to support the accuracy and verifiability of all claims made.

Congressional and regulatory reports, news investigations and expert analyses were used to ensure factual accuracy. Each citation provides context on regulations, cases, or expert quotes relevant to money laundering in the art auction sector.

colorado-banker.thenewslinkgroup.org theartnewspaper.com news.artnet.com courthousenews.com complyadvantage.com complyadvantage.com swissinfo.ch amlintelligence.com nortonrosefulbright.com napier.ai financialcrimeacademy.org int-comp.org reuters.com theguardian.com rehs.com complyadvantage.com ial.uk.com

About Our Investigative Services

Seeking to expose corruption, track illicit financial flows, or investigate complex criminal networks? Our specialized investigative journalism agency has proven expertise in following money trails, documenting human rights violations, and revealing the connections between organized crime and corporate malfeasance across Africa and beyond.

Partner With Us for Impactful Change

Ready to drive transparency and accountability in your sector?

Our investigative expertise and deep industry networks have exposed billion-dollar corruption schemes and influenced policy reform across Americas.

Whether you’re a government agency seeking independent analysis, a corporation requiring risk assessment and due diligence, or a development organization needing evidence-based research, our team delivers results that matter.

Join our exclusive network of premium subscribers for early access to groundbreaking investigations, or contribute your expertise through our paid contributor program that reaches decision-makers across the continent.

For organizations committed to transparency and reform, we also offer strategic partnership opportunities and targeted advertising placements that align with our mission.

Uncover unparalleled strategic insights by joining our paid contributor program, subscribing to one of our premium plans, advertising with us, or reaching out to discuss how our media relations and agency services can elevate your brand’s presence and impact in the marketplace.

Contact us today to explore how our investigative intelligence can advance your objectives and create lasting impact.

Read all investigative stories About Americas.

For Transparency, a list of all our sister news brands can be seen here.