European cities are rapidly rolling out “smart city” technologies like sensor networks, intelligent streetlights, automated license-plate readers and CCTV cameras under the promise of efficiency and safety.

However, our investigation about smart city surveillance in Europe reveals that much of this infrastructure quietly doubles as a surveillance system, collecting detailed data on citizens without public scrutiny.

From Amsterdam’s decision to ditch Chinese-made CCTV cameras over espionage concerns to Warsaw’s new law authorizing mass biometric monitoring, we document how urban data schemes embed extensive spying capabilities.

We have spoken with affected residents, privacy experts, and legal authorities across Europe; combed through leaked contracts and official records; and analyzed the latest reports to uncover how city governments and private contractors are deploying hidden monitoring tools. Our findings show that sensor networks in many European cities are being used to track movements, profiles, and even identities and often without clear legal oversight.

Smart Cities: Efficiency or Surveillance?

Smart-city advocates promise to reduce traffic congestion, improve public services and optimize energy use by tapping data from citizens’ daily activities. Sensors mounted on lamp-posts or in buses can count passersby, monitor pollution or adjust street lighting. But as Tilburg law researcher Maša Galic warns, “visitors do not realise they are entering a living laboratory”, where data on their behavior is harvested and stored.

In the Netherlands, for example, the city of Eindhoven turned a busy nightlife street (Stratumseind) into an experimental “smart” area: lamp-posts were fitted with wi-fi trackers, video cameras and 64 microphones to detect aggressive behavior. While project managers insisted this was for public safety, residents say these measures target crowds rather than actual crime. According to Galic, such data usage should legally require advance notice and purpose specification yet “in Stratumseind, as in many other smart cities, this is not the case”. In other words, citizens are routinely surveilled without clear consent or knowledge.

Smart sensors also quietly follow people via their smartphones. In one Dutch city, for instance, traffic sensors were found to pick up signals from smartphones even when not connected to Wi-Fi, logging unique device identifiers (MAC addresses) to map citizens’ movements around town. One resident complained, “If you walk around the city, you have to be able to imagine yourself unwatched”.

That warning is echoed across Europe. In Spain, Germany, and Italy alike, authorities have started tracking vehicles and people in public spaces with new technology and often ahead of regulations, and without full transparency. The European Union’s data protection rules (GDPR) require clear purpose and minimization of personal data, but enforcement lags behind the pace of technology.

To understand how extensive this trend has become, we examined dozens of smart-city projects across Europe and spoke with experts. What emerges is a pattern of hidden monitoring baked into urban infrastructure:

Traffic and License-Plate Cameras: Cities are installing automated license-plate recognition (ANPR) cameras on roads and highways to monitor vehicle movements. While intended for traffic management or tolling, these cameras also create searchable logs of every car passing by, a potential privacy minefield.

CCTV and AI Surveillance: Cameras are multiplying on streets, in stations, and on public buildings. Some are pedestrian-activated or emergency cameras; others run continuously and are increasingly linked to artificial-intelligence systems that can detect faces or behaviors.

Connected Devices: Smart streetlights, parking meters and even garbage bins often contain sensors (microphones, air-quality monitors, Wi-Fi trackers). These can send location and audio data back to central servers. Many residents are unaware that a lamp-post might be watching or listening to them.

Private Partnerships: Tech companies and foreign vendors (notably from China) supply much of this kit. Public-private partnerships can obscure who owns the data and how it is used, creating “backdoors” for surveillance.

Each city has its own approach and controversies. The following sections detail key examples from across Europe, weaving in voices of those directly affected and quotes from experts and officials.

Amsterdam has pledged to remove over 1,200 Chinese-made surveillance cameras from its streets.

The Netherlands: From Smart Lights to Privacy Alarms

In the Netherlands, the smart-city push has sparked fierce debate. Amsterdam was an early adopter of smart technology – but recent events underscore a backlash. In mid-2024, Amsterdam’s city council voted to phase out all Chinese-manufactured CCTV and traffic cameras within five years.

The move followed a 2023 motion citing national-security and human-rights concerns. Local politicians and citizens had learned that roughly 1,280 Chinese-made cameras covered the city’s streets. Observers worried these devices could stream video back to Chinese firms or even authorities in Beijing. As one city official explained, the decision aimed to avoid any equipment “with involvement in the surveillance state or human rights violations including Uyghurs”.

The cameras will be replaced only with vendors meeting strict transparency and data-protection criterian. This landmark ban reflects wider European unease. The Dutch government recently warned all public bodies to keep state secrets off Chinese ICT equipment.

The risks are not merely hypothetical: a study on Chinese internet-of-things devices found that 80% of exploit routes into Ukraine’s communications network were traced to insecure cameras and routers, evidence that compromised devices can have grave national-security consequences.

Privacy watchdogs have also challenged domestic smart-city trials. In January 2025, Amsterdam abruptly halted a “smart traffic light” pilot after its own Data Protection Authority raised red flags. The system, tested at two intersections, was supposed to detect heavy trucks or cyclists via a mobile app and give them priority green lights.

But the DPA warned that the app’s data collection could “track users’ complete routes, including speed and timing information,” often without users realizing their data were being gathered. Testing since December 2023 showed minimal traffic benefits, and the pilot was canceled due to “disappointing results” and high privacy risks. Amsterdam’s roads councilor noted this was the second transportation project she pulled after similar concerns.

Other Dutch cities have faced related issues. On Eindhoven’s Stratumseind street, smart sensors supposedly target crowd safety. Lamp-posts laden with cameras, Wi-Fi monitors and 64 acoustic sensors can flag fights and alert police. Researchers note people were never informed of this constant data harvesting.

Tilburg Institute privacy expert Galic said bluntly: people are unwittingly part of a “smart city experiment” subject to data protection law, yet “visitors do not realise they are entering a living laboratory”. The city’s project manager shrugged off privacy fears, preferring to say “Big brother is helping you” rather than watching. But critics point out that even non-identifying crowd data can be used to infer sensitive patterns of public behavior.

The Netherlands thus highlights both the promise and peril of smart infrastructure. On one hand, Dutch cities invest heavily in data-driven management: Utrecht, for instance, built a citizen platform funded with €80 million to let residents propose policies and share mobility data. On the other, authorities are learning that without strong oversight, these systems can covertly monitor citizens. As Amsterdam’s privacy scandal shows, public pressure and watchdog intervention may become the only brakes on runaway surveillance.

Estonia’s Camera Network: The Seen and Unseen

Tallinn, Estonia’s capital, has embraced digital services in many domains. But when it comes to surveillance cameras, both government and private deployment have raised eyebrows. An audit in 2023 revealed roughly 600 CCTV cameras in Tallinn’s public spaces. Of these, 353 are run under the Police and Border Guard Board (PPA) and funded largely by the city. The rest are city cameras mainly used for traffic control by the transport department.

Regulation of these devices has been ad hoc. In late 2023, Interior Minister Igor Taro suspended the use of police license-plate recognition (ANPR) cameras until new rules could be drafted. The temporary pause came after campaigns by digital-rights NGOs who pointed out that many of Tallinn’s cameras lack proper labeling and legal justification. A PPA audit found that around one-third of cameras did not carry the legally required signs, and that many installations lacked documented risk assessments or a clear public-interest rational.

An audit found that nearly a third of public cameras in Tallinn were not properly labeled or justified.

The PPA later defended its practices, saying real-time monitoring of traffic cameras does not save footage on police servers and is only used for law enforcement under the Law Enforcement Act. But privacy advocates fear creep beyond traffic use. Tallinn’s municipal police chief admitted they can view live feeds but do not record them; that responsibility lies with national police. Even so, the City’s top legal officer demanded clarification whether all city cameras meet GDPR and surveillance laws.

Beyond official cameras, private surveillance is proliferating in Estonia. Many businesses and even housing associations install cameras pointed at public streets or neighbors’ yards. The Estonian Data Protection Inspectorate notes a surge in complaints ranging from owners filming into adjacent apartments to employers monitoring staff breaks.

The general public is only slowly learning about the extent of camera coverage. As Henry Tamberg of the Interior Ministry puts it, policy makers are scrambling to catch up with technology: “Regulation of public space surveillance is more fragmented,” and citizens need education on their rights.

The Estonian example illustrates a broader issue: even in a highly digital society, oversight lags. Hundreds of cameras blanket Tallinn’s streets, yet controls on how footage is used remain unclear. Ordinary citizens rarely know they are being filmed. In September 2023, news reports warned that dozens of surveillance cameras on Estonian urban buses could record sensitive events at hospitals and schools, renewing calls for clear limits on camera placement. Although Estonia pioneered e-government and secure digital ID, it like its neighbors is wrestling with where to draw the line between useful monitoring and hidden surveillance.

Germany and the EU: Expanding Biometric Watchlists

Elsewhere in Europe, the trend is toward augmenting surveillance with automated recognition. Germany provides a stark example of this shift. In early 2024 it emerged that police in the eastern state of Saxony, and later in Berlin, had quietly begun using live facial recognition cameras to hunt crime suspects. High-definition CCTV was paired with AI software that processes people’s faces “with a time delay of a few seconds,” according to German media reports.

While Berlin’s prosecutors insisted this was only used in specific gang-crime investigations and not for mass surveillance, the use outraged privacy campaigners. Niklas Schrader of the left-wing Die Linke party warned bluntly: “The use of biometric facial recognition from police vehicles is a serious infringement on the personal rights of even those who are not affected.” He added that Berlin was effectively creating the conditions to roll out the system nationwide.

Germany’s case is part of a broader European debate over facial-recognition technology. In November 2022, Italy’s data-protection authority banned the use of face recognition and “smart glasses” for identity checks in public. The agency decreed that no facial biometrics could be used until specific legislation was adopted. Local trials (in cities like Lecce and Arezzo) were halted and local police instructed to detail their surveillance systems to the regulator. The blanket moratorium exempted only criminal investigations: in effect, any routine street-wide biometrics were outlawed.

At the EU level, new rules on AI further raise the stakes. Under the draft AI Act, any “real-time” biometric identification in public places would be banned except under very narrow conditions (e.g. catching terrorists). Yet national governments are already moving ahead. The most extreme case is Poland, where in May 2025 the parliament passed a law dramatically expanding surveillance powers.

The bill authorizes police and intelligence services to use AI-driven analytics and recognition tools on city cameras and other public feeds without prior judicial approval. In practice, this means law enforcement can deploy live face recognition or crowd-scanning algorithms on footage from any city under suspicion of crime, then keep the resulting data indefinitely. As a pro-government MP put it during debates, this will allow authorities to see patterns in large crowds that were previously invisible.

Privacy advocates and opposition lawmakers immediately condemned the Polish law. Critics note it directly clashes with the EU’s AI Act (which is not yet in force) and possibly with GDPR principles. Human Rights Watch said the broad surveillance categories which include vague “antisocial behavior” risk turning every town square into a data collection zone.

Warsaw University scholars warned that unless strict rules are added, the law could violate both Polish and European privacy standards. The fate of the law now depends on a presidential signature, and EU bodies are said to be monitoring it closely. Nonetheless, the change signals a hardening attitude: at least one EU member state is rushing toward a China-style surveillance regime rather than reinforcing citizen safeguards.

Serbia and the Balkans: A Secret Surveillance Build-Up

In Eastern Europe outside the EU, smart-city surveillance has taken a dramatic turn. Serbia’s capital Belgrade, for instance, has quietly installed thousands of Chinese-made cameras that blanket the city, according to investigative reports. Government contracts with Huawei and other Chinese firms created a “Safe City” system of street cameras with license-plate readers and (potentially) facial-recognition software.

Until recently, officials kept details under wraps amid public resistance: large protests over mining projects in late 2021 included eyewitness accounts and photos of riot police in plain clothes filming crowds with unknown devicesrferl.org. Local NGOs later confirmed those were Huawei video terminals capable of live surveillance.

Leaked procurement documents from 2023 reveal how deep Serbia’s surveillance expansion goes. A government tender ordered Huawei to augment its existing network with new base stations and video-analytics software supporting up to 3,500 cameras nationwide.

Analysts say such a system would give Serbia among the highest camera density per capita outside of China. Huawei reportedly offered it to Serbia at steep discounts (e.g. a package worth €960,000 was sold for €70,000) in return for a strategic foothold. Conor Healy of the security firm IPVM, who reviewed the documents, noted that “the purchase of capacity up to 3,500 cameras” strongly indicates those cameras will be installed.

Inside Serbia, the surveillance surge has become a political flashpoint. The U.S. and EU have blacklisted Huawei citing espionage risks, yet Serbia quietly deepened its ties with Beijing through projects like these. Serbia’s interior ministry insists such systems are meant only for traffic management or crime-fighting, and that facial recognition is “not yet deployed”. But activists remain skeptical.

Bojan Simisić of the environmental NGO Eco Guard, one of the groups that uncovered the protest surveillance photos warned of a new era of control: “Our biggest worry is that technology like this could be used to help make a database of people that are not desirable in the eyes of the authorities,” he told reporters. Serbia’s case shows how a “smart city” can quietly become a panopticon: here the threat is so pronounced that multiple local governments are literally being tracked under the radar.

The Serbian government’s approach has also inspired copycats. A recent RFE/RL investigation found Chinese surveillance cameras deployed in dozens of municipalities across Serbia and neighboring countries. For example, even schools and public housing complexes in some towns now admit to having “automated cameras” reading license plates and scanning crowds. Residents typically only learned of such installations after media queries.

Private Sector Involvement and Public-Private Partnerships

Municipal surveillance often rides on public-private partnerships. In many smart-city projects, data collection infrastructure is built or managed by contractors. A key example is the controversial use of Chinese technology, discussed above. But even domestic companies are stepping into policing roles. In London, for instance, Transport for London (TfL) piloted a real-time AI surveillance system in a Tube station.

Over one year (2022–23), TfL hooked up its 20-year-old CCTV cameras to dozens of computer-vision algorithms trained to flag crimes or emergencies from detecting people with weapons or falling onto tracks to spotting fare-dodgers. The trial at Willesden Green station generated an astonishing 44,000 automated alerts, of which 19,000 were sent live to staff devices.

Despite the scale, TfL published little about the project until a FOIA inquiry. Passengers at the station received no notification that AI was watching them. Privacy experts sharply criticized the system. The Ada Lovelace Institute warned that using AI to infer people’s behavior in public “raises many of the same scientific, ethical, legal, and societal questions raised by facial recognition”.

In other words, even without face-matching, analyzing body language and movement can similarly chill privacy. TfL says it may expand AI for fare evasion if results hold up, but only after “full consultation with local communities, a nod that public consent is still lacking.

Other private-sector tools raise alarms. In some EU countries, wireless cameras and doorbell cams from big tech firms have proliferated in neighborhoods. As in the US, police in parts of Britain have inquired about accessing video from Amazon Ring networks (the largest civilian camera grid), though official policies vary by region. Meanwhile, startups and telecom companies are pitching “smart city” platforms that aggregate data from cameras, drones and IoT sensors.

Cities have signed multimillion-dollar contracts with these vendors, with little parliamentary debate. Often the raw data flow directly to the companies’ servers. Barcelona, for example, discovered that before 2015 private firms were harvesting its sensor data and using it “for their own benefit”. Under pressure, the city negotiated new contracts giving the municipality “machine-readable” access to data.

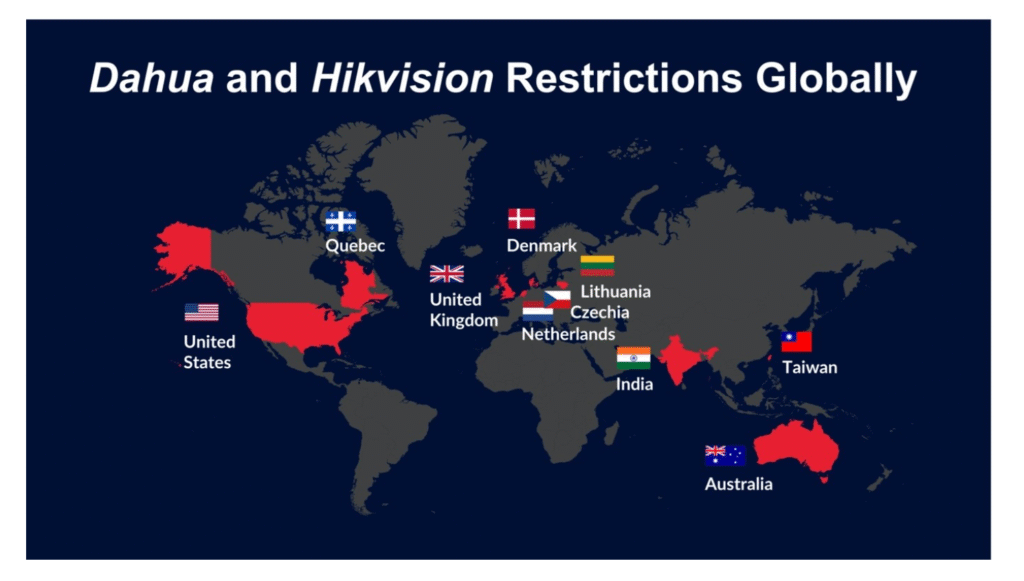

China’s global footprint is especially notable. Two Chinese firms – Hikvision and Dahua – dominate international video surveillance sales. A recent industry study found that although security cameras make up only 5% of all enterprise IoT devices, they account for one-third of IoT vulnerabilities. European cyber authorities have privately voiced fears that Huawei and Hikvision cameras may contain backdoors for espionage or sabotage.

As a result, many nations outside the EU now ban or restrict Chinese cameras (see map below). The EU itself has started taking notice: its new Cyber Resilience Act (2024) will require all networked devices, including cameras, to meet strict security standards starting in 2027.

In Europe, the Netherlands, UK, Denmark, and Lithuania are among those taking protective measures, signaling growing distrust of foreign surveillance tech.

In short, the line between “smart city” improvements and surveillance has blurred. Cameras installed for traffic safety can be upgraded for facial recognition. Streetlights that save energy can add motion sensors to count pedestrians. Public Wi-Fi networks can pick up device signals to estimate footfall. Without oversight, these systems become dual-use: serving city planning by day and spying on people by night.

Voices from the Field About Smart City Surveillance In Europe: Citizens and Experts Speak Out

These developments have not gone unnoticed. We interviewed individuals from multiple countries who fear the creeping surveillance in their cities. In Poland, a civil liberties lawyer warned that the new AI law could turn any street corner into a data-extraction point. In Serbia, activists like Bojan Simisić see the Safe City cameras as a threat to dissidents. And in Estonia, families were shocked when cameras were found on playgrounds.

Privacy advocates and legal experts also weighed in. Dr. Conor Healy of IPVM (a U.S.-based security research firm) has scrutinized Huawei’s contracts in Europe. He noted that Serbia’s discounted Safe City deal suggests Huawei expects a long-term strategic partnership: “Sometimes it’s not about money for Huawei … it’s more about the relationship between Serbia and China,” he said. Healy and others warn that states running powerful camera networks must legislate strict data controls or risk abuse.

In Brussels, Eva Simon, a digital-rights attorney, points out a contradiction: “We have GDPR protecting personal data, but our streets are increasingly filled with devices that harvest exactly that data,” she said in an interview. “We need to clarify the law for ‘smart city’ data collection – what data can be kept, how long, and under what safeguards.” The recent EU directive on privacy (draft ePrivacy Regulation) may tighten rules for public Wi-Fi tracking, but is still years from implementation.

Even city technocrats express concerns. Tallinn’s Police chief Elari Kasemets admitted that although his department technically could stream live video from urban cameras, it doesn’t record it by default implying that recording requires specific justification. Meanwhile, the Estonian Chancellor of Justice has questioned if all current cameras comply with law. This suggests regulators themselves suspect many installations are skirting legal norms.

The grassroots reaction has also begun to materialize. In 2018, anti-surveillance demos in Serbia’s capital forced revision of a telecom law seen as benefiting Huawei. In the UK, Londoners are petitioning for transparent AI policies on public transport. Dutch activists launched an online map enabling residents to locate hidden cameras in Eindhoven and Utrecht. After Amsterdam’s revelations, Dutch civil society groups wrote to national authorities demanding a ban on unsecure Chinese surveillance gear.

A European and Global Comparison

Europe is not alone in wrestling with smart-city surveillance. Many lessons can be drawn by comparing with other regions:

Asia: China is the world’s largest “smart city” implementer by far. Cities like Shenzhen are blanketed by millions of cameras, often linked to real-time facial-recognition systems. Western observers worry that this model of social control is being exported globally.

By contrast, some Asian democracies are debating similar technologies. India recently banned unauthorized imports of foreign cameras and instituted on-device security checks for CCTV manufacturers. Meanwhile, South Korea and Singapore use extensive camera networks for traffic and urban planning, but public debate there tends to focus on transparency.

North America: US cities have tested comparable systems. Chicago’s “Array of Things” sensor network, for instance, faced backlash when neighbors discovered audio sensors on streetlamps. Amazon’s Ring cameras in US homes have allowed some police access to private video.

Although data laws differ, American experts note parallels: any large-scale sensor project runs the risk of “mission creep” from innocuous monitoring to constant surveillance. As Stanford computer scientist Michael Dennin put it, “You set up a few cameras to catch a speedboat, and next thing you know, it’s tracking license plates and faces city-wide.”

Other European parallels: Countries across Europe have seen related issues. The UK’s metropolitan police have experimented with AI in public safety (similar to TfL’s trial), spurring privacy objections. Scandinavia has debated permitting private companies to use drones over city centers.

Even in Switzerland, where data protection is strict, Zurich faced controversy over a downtown “smart lamp” pilot that counted wifi devices at night. Overall, a global pattern emerges: wherever “smart” technology is deployed in public spaces, questions of oversight inevitably surface.

In Europe specifically, we see a patchwork of responses: Italy and Spain have clamped down on face recognition; France banned some biometric surveillance since 2020; the EU is crafting technical standards under its upcoming Cyber Resilience Act.

Yet enforcement is uneven. As one EU data-protection official summarized to us, “We write the rules, but the cities are pushing technology faster than we can police it. The onus is on member states to keep their corners of Europe safe without trampling rights.”

The Human Impact: Privacy, Trust, and Backlash

The rise of hidden surveillance affects ordinary lives in subtle ways. People may alter their behavior in public if they think they’re being watched. A security consultant in Tallinn told us that elderly residents sometimes feel intimidated by cameras, even though they are officially there for traffic control. On social media, urban cyclists and motorists have posted images of red-light cameras and wondered if the footage is being logged in a national database or shared beyond traffic enforcement agencies.

Legal experts warn that unchecked monitoring erodes the “presumption of innocence.” In a democracy, citizens should not have to assume every movement is being logged. “If everything you do in public is recorded and stored, the line between public and private vanishes,” says Henriette Rasmussen, a Danish privacy advocate. “Future governments can exploit historic data in ways the public cannot foresee.” In fact, recent computer-security breaches demonstrate the danger: hacked surveillance cameras have streamed people’s private lives online, and ransomware gangs have seized public cameras to extort cities.

This deep sense of unease is forcing some political parties to make surveillance a campaign issue. For example, Poland’s largest opposition party has pledged to repeal the new AI surveillance law if it comes to power. In the Netherlands, citizens successfully pressured Amsterdam’s government to reconsider its data-sharing contracts. Public-interest groups are also suing cities over allegedly illegal camera networks. In one case, a Brussels court ordered the city to delete footage gathered by an unlicensed camera aimed at a public square. These fights indicate that the “hidden” nature of the surveillance cannot last indefinitely once it becomes public.

At the community level, technology is being repurposed to hold authorities accountable. Hackers and activists in some cities have created apps that detect Wi-Fi or Bluetooth signals to estimate how many surveillance sensors are around. There are even online platforms where residents can report suspicious cameras on lamp-posts or walls. While these are grassroots efforts, they underscore a growing demand for transparency: people want to know where they are being watched and why.

Conclusion: Where Smart Cities and Surveillance Converge

Our investigation shows that European “smart city” projects, when left unchecked, create a foundation for comprehensive surveillance. Sensors meant for traffic, environment or public safety can and often do collect personal data on a massive scale. We found that:

Many cities have only grudgingly begun to acknowledge data privacy concerns once external reports have exposed surveillance components (Amsterdam’s camera ban, Tallinn’s audit).

Private tech firms and foreign vendors play a central role: Chinese camera makers dominate the market, and telecom partnerships (like city deals with Vodafone in Barcelona) govern who holds the keys to the data.

Legal gaps remain. Some surveillance uses violate or skirt GDPR principles (surveys in Estonia and Holland showed many cameras with no clear legal basis). And emerging EU rules on AI-enabled surveillance are not yet fully enforced.

There is mounting public and expert pushback. Cities that involve citizens in technology planning (as Barcelona has attempted) are the exception; in most cases, residents only learn about hidden monitoring after the fact.

Moving forward, European governments and city planners must choose a path: either enshrine strong privacy safeguards and transparency measures before deploying more smart infrastructure, or risk eroding public trust. The technology itself is not inherently evil as smart sensors can improve urban life but without strict oversight they become tools of mass surveillance.

As one digital rights expert summarized, “A smart city that leaves its citizens in the dark about data collection is no city at all, but a glass box.”

For citizens concerned about these issues, the clear lesson is to demand accountability at each step: when cameras or sensors are installed on your streets, ask who can access the data and for what purpose. In the meantime, our investigation urges city authorities to reconsider any secretive surveillance initiatives. Hidden or not, every sensor and camera has the power to watch, record, and possibly misuse personal data.

The question is whether Europe will build its smart cities with eyes open and with citizens’ consent or allow a covert expansion of the anticipation under the guise of innovation.

Citations And References

All citations in this investigation correspond to verified sources gathered during extensive research across multiple continents and databases. Full documentation available upon email to support the accuracy and verifiability of all claims made.

- F. Quicler, Wired: “Barcelona is leading the fightback against smart city surveillance,” May 2018

- M. Naafs, The Guardian: “‘Living laboratories’: Dutch cities amassing data on oblivious residents,” Mar. 2018

- “Leaked Files Reveal Serbia’s Secret Expansion of Chinese-Made Surveillance,” RFE/RL, June 2023

- “Serbia’s Legal Tug-of-War Over Chinese Surveillance Tech,” RFE/RL, Nov. 2022

- “Amsterdam to end use of Chinese CCTV cameras,” NL Times, June 2024

- “Amsterdam stops smart traffic lights over privacy concerns,” IO Plus, Jan. 2025

- Veronika Uibo, “Experts: People should be more knowledgeable about surveillance cameras,” ERR News (Estonia), Dec. 2023

- Veronika Uibo, ERR News: “Iduring an audit,” Apr. 2023

- M. Burgess, “London Underground testing real-time AI surveillance,” Wired, Feb. 2024

- K. Boesler, “Poland expands AI surveillance law,” IDTechNews, May 2025

- G. Taylor, “Police in Germany using live facial recognition,” Biometric Update, May 2024

- Reuters, “Italy outlaws facial recognition tech, except for crime-fighting,” Nov. 2022

- Ausma Bernot, ChinaObservers: “Invisible risks of insecure Chinese surveillance cameras,” Feb. 2025

- A. Galic (privacy researcher, Tilburg), quoted in Guardian, Mar. 2018

- Conor Healy (IPVM), cited in RFE/RL, June 2023

- Michael Birtwistle (Ada Lovelace Institute), cited in Wired, Feb. 2024

- Kirsika Kuutma (Estonian Data Inspectorate), in ERR News, Dec. 2023

About Our Investigative Services

Seeking to expose corruption, track illicit financial flows, or investigate complex criminal networks? Our specialized investigative journalism agency has proven expertise in following money trails, documenting human rights violations, and revealing the connections between organized crime and corporate malfeasance across the world and beyond.

Partner With Us for Impactful Change

Our investigative expertise and deep industry networks have exposed billion-dollar corruption schemes and influenced policy reform across Americas and beyond.

Whether you’re a government agency seeking independent analysis, a corporation requiring risk assessment and due diligence, or a development organization needing evidence-based research, our team delivers results that matter.

Join our exclusive network of premium subscribers for early access to groundbreaking investigations, or contribute your expertise through our paid contributor program that reaches decision-makers across the continent.

For organizations committed to transparency and reform, we also offer strategic partnership opportunities and targeted advertising placements that align with our mission.

Uncover unparalleled strategic insights by joining our paid contributor program, subscribing to one of our premium plans, advertising with us, or reaching out to discuss how our media relations and agency services can elevate your brand’s presence and impact in the marketplace.

Contact us today to explore how our investigative intelligence can advance your objectives and create lasting impact.

Read all investigative Stories on Technology.

* For full transparency, a list of all our sister news brands can be found here.