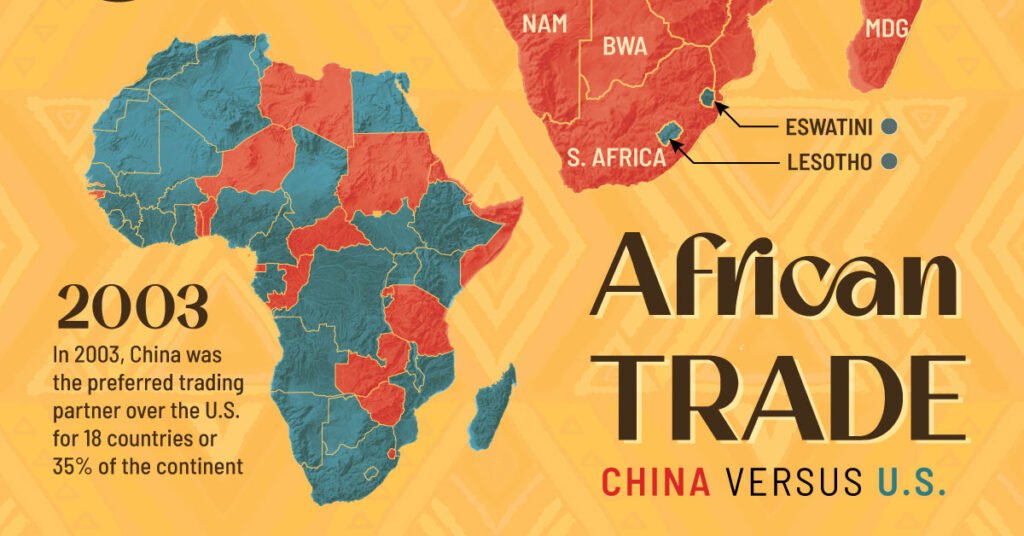

Over the past two decades, China has dramatically expanded its economic footprint in Africa financing highways, ports, dams and factories with billions of dollars of loans and investment. This surge has reshaped trade relations on the continent: by 2023 fully 52 of Africa’s 54 countries were trading more with China than with the United States, a striking reversal from just 20 years prior. This investigation reveals shocking patterns about how Chinese Investment In Africa often leads to controversial influences on political powers in Africa.

In return, African governments have leveraged Chinese funds to pursue ambitious infrastructure and development plans. Yet alongside tangible gains like new roads, jobs and industrial parks, critics warn that Beijing’s capital comes with strings attached, subtly steering national policies and undermining sovereignty.

This investigation reveals how Chinese investment affects African political decision-making, drawing on data, expert analysis and on-the-ground accounts to probe the full scope and limits of Beijing’s influence.

In Africa’s capitals, the story is often told in dollars and dollars of infrastructure. China’s state banks and companies finance and build major projects: railways in Kenya and Tanzania, ports in Djibouti and Angola, power plants in Zambia and Uganda. African leaders often hail these projects as lifelines.

“Chinese capital is helping accelerate Africa’s growth, particularly in infrastructure and industrial development,” Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni proclaimed in 2025 at a development summit, noting Chinese-built power dams and industrial parks that generate thousands of jobs. Indeed, projects like the Addis Ababa–Djibouti railway and Uganda’s Isimba and Karuma dams stand as visible symbols of China-funded progress.

For many officials, Chinese investment means new roads and factories that Western donors long avoided. China’s President Xi Jinping emphasizes exactly this message, pledging “no political strings attached” loans and unfettered support for African development.

Yet in private and on street corners, the narrative is often more complex. African business owners and citizens sometimes complain of trade imbalances and lost markets. Labor activists note local jobs replaced by imported Chinese workers or materials. Opposition politicians and civil society groups occasionally warn of looming debt burdens and undue influence in national politics.

In recent years, some African presidents and parliaments have quietly asked: who really benefits when Chinese-built highways, paid for with government loans, come due for repayment? This story unfolds amid rising global scrutiny of China’s role in Africa – questions raised by Western governments, international media and occasionally by Africans themselves about whether China’s ascent is a win-win partnership or a new form of leverage over African states.

A New Era of Engagement: Scales and Sectors of Chinese Investment

China’s engagement in Africa is built on a complex mix of loans, equity investment and government-to-government contracts. Through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and other channels, Beijing has poured capital into nearly every African country.

Official figures show China disbursing tens of billions of dollars across the continent every few years. At the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) in 2024, Xi Jinping announced fresh support of roughly $51 billion over three years for African development. Yet much of that is earmarked as trade credit or behind-the-scenes financing (for example, lines of credit to state firms), so actual on-the-ground investment follows different contours.

Independent data help quantify the scale. U.S.-based researchers charted Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) flows to Africa at around $4.0 billion in 2023. (By contrast, U.S. FDI was almost double at $7.8 billion that year.) China’s FDI to Africa remains modest compared to its global investments, often concentrated in resource-rich countries like Niger, Angola and the Congo.

But beyond FDI, Chinese banks have also extended massive loans for infrastructure, tracked by entities like AidData. For example, China’s sovereign lending to African governments peaked near $28 billion in 2016, though it later fell back as African borrowers slowed payments. Observers estimate that, across all sectors and years, China’s financial commitments on the continent total in the low hundreds of billions (some estimates around $150–200 billion) since the early 2000s.

The lion’s share of Chinese investment in Africa has gone into key sectors: energy, mining, transport infrastructure and telecommunications. Major African mines for cobalt, copper, gold and oil often have Chinese partners or buyers. Ports and railways built by Chinese engineers link landlocked countries to the sea (e.g. the Tanzania-Zambia Railway or the new rail out of Guinea’s Simandou iron deposits).

Chinese state firms have built dozens of hydroelectric dams, including many of Africa’s largest (like Ethiopia’s Merowe or DRC’s Inga III proposals). In telecom, China’s Huawei and ZTE have provided network equipment and tech, spreading Chinese digital standards. More recently, Chinese capital is funding manufacturing and agro-industrial parks – from Nigeria’s Lekki Free Trade Zone to factories in Ethiopia – often as part of China’s strategy to globalize its own industries.

These investments can be mutually beneficial: African economies get needed infrastructure and jobs, while China gains raw materials, markets and geopolitical partnership. The China Africa Research Initiative notes that “infrastructure improvement, job creation, and overall economic growth” are among positive impacts.

For example, roads built by Chinese contractors have dramatically reduced travel times in Kenya and Ghana. Power plants have lifted grid capacity in countries like Zambia and Ethiopia. Such tangible gains bolster Chinese goodwill among populations that value development.

But this economic footprint also brings questions of influence. When a government depends heavily on Chinese financing, it may think twice before upsetting Beijing. Critics argue that over time, the flow of Chinese money to select projects and sectors subtly shapes policy priorities and empowers leaders who back China. The notion of “debt-trap diplomacy” – the idea that China deliberately lends too much to extract political concessions later – has become a rallying phrase, though experts debate its accuracy.

What is clear is that Chinese loans have come with different (often fewer) overt conditions than Western aid – Beijing insists on a non-interference principle in politics, as Xi himself proclaimed at the 2018 FOCAC: “China does not interfere in Africa’s internal affairs and does not impose its own will”. This unconditionality is a selling point for many African rulers, who contrast it with World Bank or IMF loans that typically require economic reforms and governance changes.

However, critics see a flip side: “no strings” may mean there is little requirement for transparency or environmental safeguards. And without pressure to improve governance, some African governments may become more tolerant of corruption or repression, counting on China’s uncritical support. For instance, Zimbabwe’s government, long shunned by the West, has relied on Chinese backing for new mines and lines of credit, arguably sustaining an authoritarian regime.

Likewise Sudan and Sudanese breakaway region Darfur received Chinese military equipment and investment even as human rights conditions worsened, because Beijing’s non-interference stance let Khartoum ignore Western demands.

Political Implications and Case Studies

To illustrate the influence of Chinese investment on decision-making, consider a few country examples:

Kenya

Kenya is Africa’s largest borrower from China. Chinese banks funded the $3.8 billion Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) from Nairobi to Mombasa – a signature project of the previous administration. The new government under President William Ruto has faced a heavy debt bill: Kenya now owes over $8 billion to China, and servicing these loans consumed about a quarter of public revenues.

In 2023 Kenya sought Chinese help: Ruto requested a $1 billion loan and debt relief to finish stalled projects like highways and the unfinished extension of the railway. Analysts note that Kenyan authorities have been forced to re-prioritize their budget due to Chinese debt. In fact, some recent public unrest was linked to austerity measures needed to pay debts, including those to China.

Alex Vines of Chatham House has pointed out that “deadly protests in Kenya were triggered by the government’s need to service its debt burden to international creditors, including China”. Domestically, opposition politicians have criticized Chinese contracts for lacking local transparency; civil society groups demand more say in project planning.

Zambia

In Zambia, Chinese involvement has likewise been deep and controversial. After borrowing heavily to build roads and power lines, Zambia became the first African country to default during the COVID-19 era. Its President Edgar Lungu accused Western donors of magnifying fears about Chinese loans, even as the country’s debt slump opened space for Beijing to step in with financial support.

Notably, Chinese lenders quickly provided new aid in 2021 when Zambia secured an IMF program – contrasting with Western reluctance without strict conditions. Critics allege Chinese banks have obtained concessions like mining stakes in return. Though Zambia’s leaders insist any support is aimed at development, skeptics say the deals reduce Zambia’s future policy independence.

Ethiopia

Ethiopia under Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed signed off on Chinese investments in industrial parks and railway lines, as part of its modernization push. However, when conflict erupted in Tigray in 2020, Western governments cut off aid, whereas Chinese companies largely continued business. Some analysts suggest Beijing used the opening to solidify ties; for example, China secured a favorable agreement for a new Chinese-operated port in Eritrea, giving it an outlet to the Red Sea.

Meanwhile, Ethiopian officials have at times needed to balance Chinese influence with Western relationships. In 2022, Ethiopia’s parliament (after pressure from opposition parties) investigated how China had obtained stakes in several sectors. The episode illustrated the complex dance: Ethiopia’s government welcomed Chinese funds for development, but legislators sought greater oversight after public complaints.

Nigeria

Africa’s most populous country has been courted vigorously by Beijing. China Bank loans financed some Nigerian power plants and refinery rehabilitation. Yet locals complain that promised benefits often go unrealized. For example, Chinese-built roads in Lagos were delayed and contested, leading to public frustration.

Nigerian leaders, aware of multiple external pressures, try to negotiate: in recent years they resisted any one source of funding dominating the agenda. For instance, Nigeria’s leadership granted 5G permits to both Huawei (China) and European companies to hedge. Still, China’s economic clout clearly gives it leverage in diplomacy with Abuja: Nigeria often speaks sympathetically about Chinese policy (including on the South China Sea issue), reflecting aligned interests.

Zimbabwe

After Zimbabwe’s political isolation in the West, President Emmerson Mnangagwa pivoted to China for new capital. China offered new loans and investment in exchange for Zimbabwe’s support on international issues. A prominent example: in 2020 Zimbabwe voted against a UN motion condemning Hong Kong security laws, breaking its previous alignment with Western positions, a decision that analysts link to a $600 million Chinese loan package announced around the same time.

Critics in Zimbabwe say Chinese mining contracts were hastily awarded to crony companies, feeding allegations that government figures captured windfalls. Chinese involvement has expanded Zimbabwe’s platinum mining, but human rights advocates question the conditions of Chinese-run mines and the close ties between Chinese firms and the ruling party.

Djibouti

This small Horn of Africa nation illustrates geopolitical dimensions of China’s footprint. China funded 75% of the $590 million Doraleh Multipurpose Port and established its first overseas military base here in 2017. As Djibouti’s government secured these projects, some analysts noted that Djibouti shifted its voting at international forums more closely in line with China’s interests.

For example, Djibouti has been silent on issues sensitive to Beijing (like treatment of Uyghurs or Hong Kong), earning criticism from human rights groups. In effect, Djibouti’s leadership appears content to trade territory and policy alignment for Chinese investment and security guarantees.

These cases reflect a range of outcomes. In some instances, Chinese funding pushes forward projects that might otherwise have stalled; in others, it arguably entrenches leaders by filling national coffers. Across Africa, a common thread is that Chinese deals come without the governance conditions typical of Western aid which can be both good news (for swift execution) and bad news (for transparency and accountability).

As an African government official told Reuters, Chinese financiers emphasize “actively developing new modes of cooperation” but also encourage African partners to avoid what China sees as burdensome conditions. In practice, this approach has made China a popular partner among sitting governments, especially those keen to avoid criticism of their human rights records or fiscal policies.

Contested Narratives: Sovereignty, Debt and Governance

The question of influence hinges on perspective. Chinese sources and many African officials emphasize African agency. At a 2021 summit, Xi insisted Africa “has the right, capacity and wisdom to choose its partners”, framing the relationship as equal. Uganda’s Museveni echoed this by urging Western donors to be as generous, praising Chinese investment’s “promise of good returns”.

Numerous African leaders have reciprocated by publicly lauding China. For example, President Macky Sall of Senegal has repeatedly thanked Beijing for financing Dakar’s new port and toll roads, adding that Chinese loans came without the “political fees” imposed by others.

Yet other voices warn of a loss of policy autonomy. U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton famously cautioned in 2011 about a “new colonialism” if outsiders undermined governance. While phrased politically, her concern resonates with some African critics today: that foreign money can allow entrenched elites to sidestep accountability.

Indeed, research has found instances where Chinese aid and investment intersected with corruption scandals. A 2019 analysis by the Wharton School noted “accusations of increased corruption in Africa, bribery and unfair business practices” associated with Chinese deals. In Zambia, leaked documents in 2020 revealed that a Chinese firm was demanding an unusually high share of profits from a major mining joint venture, raising suspicions of cronyism.

In the DRC, activists have alleged that Chinese companies providing loans for mines have done so through opaque offshore entities that obscure who truly benefits.

Debt is perhaps the most cited vector of influence. Critics often point to heavy Chinese lending as a tool for leverage: if an indebted country struggles, it might have to relinquish assets or policy room to meet Chinese terms. In 2018 a group of U.S. senators warned African leaders that China’s loans were designed “to influence national policies” and gain control of strategic resources.

The oft-repeated example is Sri Lanka’s Hambantota port (in Asia): unable to repay Chinese loans for the project, Sri Lanka handed a 99-year lease to China in 2017. African skeptics worry similar deals could emerge if debts go unpaid. Even in Africa itself, some projects have been restructured under Chinese terms. In Zambia, after renegotiations, Zambia’s national electric company partly shifted to Chinese management. And when Djibouti fell behind on loan payments, China reportedly let Djibouti continue operations rather than seizing assets, but some fear this showed Djibouti’s dependence.

However, experts caution against simplistic “debt trap” narratives. Detailed analysis from the China-Africa Research Initiative notes that in many African countries Chinese loans are only one slice of overall debt. For the most part, African leaders have continued to borrow from multiple sources – Western bond markets, other governments, private banks – diluting any single creditor’s power.

For example, Ethiopia’s foreign debt portfolio includes Chinese, Japanese and World Bank components, so no single lender dictates terms. Moreover, unlike the Hambantota case, China typically does not take equity in strategic ports or mines as a blanket policy (although isolated cases exist). Chinese lenders often exercise caution themselves – the Zambia default in 2020 was widely reported as forcing Beijing to heed IMF advice rather than gaining a spoils. In fact, recent reports suggest China is seeking to convert more new projects into joint ventures (taking equity stakes) rather than pure loans, in order to ensure some commercial oversight.

Nonetheless, the political signal effect is real. Countries deep in Chinese contracts sometimes feel diplomatically obliged to back China in international forums or bilateral matters. For example, of the few African nations that have dissented from China’s positions at the United Nations on issues like Xinjiang or the South China Sea, most have minimal Chinese involvement. Major recipients like Kenya, South Africa or Nigeria routinely support Beijing’s diplomatic agenda.

This alignment is not accidental: it reflects mutual interest and possibly subtle reciprocity. South Africa’s “One China” policy was reaffirmed amid heavy Chinese trade, and leaders from Nigeria to Sudan have pledged to protect Chinese investments at home. An outspoken example: in 2021, after diplomatic pressure from Beijing, several African governments backtracked on recognizing Chinese sovereignty claims in the South China Sea, underscoring China’s clout in return for continued economic partnership.

At home, some African politicians use Chinese ties to bolster their standing. An autocratic leader might highlight Chinese support as evidence of international legitimacy, even as human rights groups protest. China’s chequebook diplomacy can undermine Western sanctions or aid conditionality: for instance, Zimbabwe’s Mugabe era survived decades of Western censure partly because China kept investing in its mines and infrastructure.

Newly elected or fragile governments also face tough choices: accept Chinese aid without Western oversight but risk anti-China sentiment, or refuse Beijing’s offer and face infrastructure shortfalls. These trade-offs shape policy debates. In Nigeria, lawmakers have disputed portions of a Chinese loan agreement negotiated in secret; in Angola, a change in leadership after civil war complicated Chinese debt deals established under the previous regime.

Comparative Perspectives Beyond Africa

China’s approach in Africa is mirrored in other regions, offering cautionary parallels. In Asia, Sri Lanka’s experience with the Hambantota port has become emblematic – when the country defaulted on Chinese loans, it gave China a 99-year lease on the strategic port. Though Chinese officials contest the “debt-trap diplomacy” label, the saga shows how heavy borrowing can lead to long-term Chinese presence.

Similarly, Malaysia in 2019 canceled or renegotiated multi-billion-dollar Chinese projects (a railway and pipeline) after public outcry over costs and alleged kickbacks. Those cancellations demonstrated that borrowing nations could reassert control by raising governance concerns, but also underscored the political costs of too much Chinese debt.

Latin America has its own analogues: countries like Ecuador and Venezuela saw a surge of Chinese loans for oil exports, with critics noting that these debts often came without transparency. In Ecuador, when a president tried to unwind some Chinese oil-for-loan deals in the mid-2010s, Beijing reportedly reviewed repayment terms only after receiving concessions (though ultimately China did not seize its portion of oil assets).

Even some European countries are now debating Chinese-funded infrastructure; e.g., parts of Eastern Europe have scrapped Chinese telecom plans over security fears. These cases all highlight a global pattern: Chinese capital flows rapidly where others hesitate, but political scrutiny follows when debts mount or public expectations go unmet.

Voices From the Ground

Local stakeholders offer varied perspectives. Business leaders in Africa often welcome Chinese investment for its speed and scale. For instance, Kenyan traders applaud the Mombasa port expansion by a Chinese firm, noting faster cargo throughput. Factory workers in Ethiopia’s Chinese-built parks say the jobs are crucial to reducing unemployment. “We appreciate that Chinese companies invest without asking for political favors, they just want business,” explains an Ethiopian factory manager.

Conversely, some community groups voice grievances. Farmers displaced by the Tanzania-Zambia railway complained they received inadequate compensation. Nigerian labor unions have protested that Chinese construction firms bring their own workers and pay low wages, undermining local labor markets. In Zambia, mineworkers have alleged unsafe conditions at Chinese-run mines. These stories often fuel suspicion that Chinese deals benefit a few insiders at the expense of ordinary citizens.

Legal and policy experts warn of long-term risks. “Even if China claims non-interference, money talks,” says an African governance scholar. “A government reliant on Chinese loans may be reluctant to criticize China’s actions, out of fear of losing the next tranche of funding.” International human rights lawyers point out that when infrastructure contracts are negotiated in secrecy, populations have little democratic input. For example, community activists in the Democratic Republic of Congo are suing over the terms of a Chinese-built highway passed without environmental review.

Journalists have documented episodes of corruption linked to Chinese projects. One notable investigation by the Center for Public Integrity uncovered that in Angola and Zimbabwe, top officials used complex offshore networks to siphon benefits from Chinese resource deals. Such exposés underscore that Chinese investment intersects with existing governance challenges, though some experts note that similar issues have plagued Western investment historically as well.

Meanwhile, Chinese officials and affiliated think tanks emphasize partnership. Beijing repeatedly argues that African problems were often created or overlooked by former colonizers, and that China offers a fresh model of “South-South” cooperation. At FOCAC meetings, Chinese delegates from ministries remind African leaders of a “shared future” vision and urge them not to accept foreign lectures on governance.

In private briefings, Chinese embassy staff stress that recent debt troubles (for example, Mauritius and Belize defaulting on Chinese loans) were due to global shocks, and that renegotiations prove China’s willingness to be flexible.

Sectors and Trends: Where Influence is Felt

Chinese investment patterns also shape politics by sector. In energy, the race for critical minerals has entwined governments with Chinese buyers. In Congo, government policy on cobalt mining shifted to favor joint ventures with Chinese firms, leading to protests from local artisanal miners who feel squeezed out.

Chinese-owned power plants give Beijing influence over national grids and commerce: Zambia’s Luapula hydropower, built on Chinese loan, has contractual clauses that could force higher tariffs if not repaid.

In telecoms and tech, Chinese companies like Huawei have become major contractors. Decisions by African governments to let Huawei build 5G networks have raised hackles in Western capitals, but African officials often say China’s offers come at a lower cost and without data-sharing demands.

The risk, critics argue, is that dependence on Chinese tech can give Beijing access to sensitive communications infrastructure. Still, so far few African leaders have banned Huawei outright, instead opting for oversight measures. Politically, any suggestion that a government ban Huawei (as the US did) has been met with diplomatic pushback.

In security and military, Chinese loans are rarely conditional on arms deals, but the overlap is common. Dozens of African officers train in China each year, and Chinese surveillance equipment is sold to various governments. The presence of China’s sole foreign military base in Djibouti ties into diplomatic relationships: overflights of Chinese naval vessels often coincide with new aid announcements.

Many African governments publicly rebuff claims of “strings attached,” but opposition figures in some countries question whether hosting Chinese troops might entangle them in Beijing’s strategic interests.

In agriculture and land, Chinese companies have leased or acquired large tracts for farming and cattle. In Ethiopia’s Alitash area and Kenya’s Rift Valley, Chinese investors operate plantations. Local reactions vary: some praise job creation, while others accuse investors of land grabs that displace smallholders.

National governments often support the deals as a way to bring technology, but civil society warns they undermine food sovereignty. Here, as in other sectors, African political debates have become more polarized, with government ministers defending the investments and critics (including some opposition MPs) pushing for reviews of land contracts.

A notable trend is that Chinese investors increasingly demand equity in projects to align incentives. Reuters reports that Chinese firms now prefer joint ventures (special-purpose vehicles) in Africa’s infrastructure projects. This shift means African governments might cede some control to these corporate partners, making them less like simple contractors and more like co-owners.

That can blur lines of accountability: if a Chinese-backed railway falters, both Chinese and African actors share the fallout. Politically, joint ownership also means project decisions require multinational agreement – potentially giving Chinese firms indirect sway over policy.

Public Opinion and Geopolitics

On the whole, African public opinion on China is mixed but not uniformly negative. Surveys show many Africans appreciate Chinese-built roads and affordable goods, even if they note downsides in jobs and governance. At the same time, a sense is growing that the international context has changed.

With the U.S., EU and other powers emphasizing “transparency” and labor rights, African civil society groups are demanding similar standards of Chinese investors. In some countries, public hearings have been held (e.g. Kenyan National Assembly sessions on Chinese loan terms), indicating democratic pushback.

Geopolitically, China’s influence on African policy is part of a larger great-power contest. The U.S. and Europe have launched their own infrastructure initiatives (like the Build Back Better World) to counter China’s pull. African leaders find themselves courted by multiple partners; they try to extract the best deals from each. In 2023, for example,

Zambia invited both Chinese and American consortia to build new rail lines, playing off one against the other. South Africa, a BRICS member, balances its trade with China against alliances with Western capitals. In some cases, African states have used Chinese offers as leverage in negotiations with old allies – for instance, Ethiopia asked Western donors to match Chinese interest on loans for road construction.

The politics is dynamic. A 2023 editorial by the African Leadership Magazine noted that “countries with significant Chinese investment are not faring much better” than those depending on Western aid. In other words, Chinese presence has not magically solved governance issues, in some places it has even entrenched them by providing alternative funding to spendthrift regimes.

Others argue that the true comparison is between a multipolar world and one where African decisions were made under Western hegemony. Indeed, China loudly positions its involvement as empowering African choice, not eroding sovereignty.

Conclusion: Navigating Opportunity and Risk

Chinese investment in Africa presents a paradox for the continent’s political leaders. On one hand, it brings opportunities: roads, power, factories and trade networks that can jumpstart development without the overt political conditions of Western aid. On the other hand, it creates dependencies on loans, on a major trading partner, and on foreign expertise that can constrain policy options.

African decision-makers have learned to handle Chinese influence with both embrace and caution. Some have aggressively courted Chinese projects and even craved them as proof of progress. Others have paused deals for renegotiation or demanded transparency after public outcry. All have had to weigh the immediate benefits of Chinese money against long-term questions of debt and sovereignty.

In many African countries, there is a growing consensus that neither blind acceptance nor wholesale rejection of Chinese investment is wise. Instead, some governments are pursuing a balanced strategy: diversifying funding sources, tightening contract terms, and leveraging global competition to get better deals. At the same time, public demand for good governance is rising.

Journalists and civil society watchdogs in Zambia, Nigeria, Senegal and elsewhere now scrutinize Chinese contracts as closely as they do Western ones. Parliaments hold hearings, and courts sometimes intervene in deals perceived as corrupt. In several cases, China itself has shown willingness to renegotiate terms when the political climate in a partner country shifts.

For African voters and activists, the story of China’s influence is still unfolding. Some celebrate Chinese partnerships as exactly the kind of global south solidarity Africa needs. Others decry a new power pattern that feels eerily like the old colonial squeeze. What is clear is that the era of small Chinese presence is over: Beijing now has hundreds of billions invested and high stakes in Africa’s stability and policies.

For African political leaders, the calculus is complex. They must navigate Chinese demands as deftly as they do those of all foreign partners, ensuring that decisions – from which mines to allow foreigners to develop to which voting blocs to join, ultimately serve their nations’ interests.

In sum, Chinese investment has an undeniable impact on African political decision-making, but it is not a monolithic force. Rather, it acts as one of several influences – alongside Western aid, domestic politics, and private-sector investments shaping how African countries chart their futures.

The “no strings attached” policy that China touts has, in practice, meant more autonomy for African governments in the short term, but it also means they must bear greater risks and costs themselves if projects fail. As new data suggests (for example, much Chinese lending now goes to special purpose vehicle partnerships), both Chinese and African policymakers seem intent on creating projects that are commercially viable.

The ultimate test will be whether infrastructure and industry built today by Chinese capital can stand on their own and benefit African economies and whether political leaders use that breathing room to invest in people and institutions, rather than deepen dependency.

Citations and references

All citations in this investigation correspond to verified sources gathered during extensive research across multiple continents and databases. Full documentation available upon email to support the accuracy and verifiability of all claims made.

- Reuters: “Post-COVID, China is back in Africa and doubling down on minerals”, May 2024

- Reuters: “Malaysia to cancel $20 billion China-backed rail project: minister”, Jan 2019

- Xinhua (Chinese state media): “Chinese capital driving Africa’s development: Ugandan president”, Sept 2025

About Our Investigative Services

Seeking to expose corruption, track illicit financial flows, or investigate complex criminal networks? Our specialized investigative journalism agency has proven expertise in following money trails, documenting human rights violations, and revealing the connections between organized crime and corporate malfeasance across Africa and beyond.

Partner With Us for Impactful Change

Ready to drive transparency and accountability in your sector?

Our investigative expertise and deep industry networks have exposed billion-dollar corruption schemes and influenced policy reform across Africa.

Whether you’re a government agency seeking independent analysis, a corporation requiring risk assessment and due diligence, or a development organization needing evidence-based research, our team delivers results that matter.

Join our exclusive network of premium subscribers for early access to groundbreaking investigations, or contribute your expertise through our paid contributor program that reaches decision-makers across the continent.

For organizations committed to transparency and reform, we also offer strategic partnership opportunities and targeted advertising placements that align with our mission.

Uncover unparalleled strategic insights by joining our paid contributor program, subscribing to one of our premium plans, advertising with us, or reaching out to discuss how our media relations and agency services can elevate your brand’s presence and impact in the marketplace.

Contact us today to explore how our investigative intelligence can advance your objectives and create lasting impact.