In India’s energy landscape, coal remains both a lifeline and a curse. The country has the world’s fourth‑largest coal reserves and has historically relied on the black fuel to power its industrialization. From the steel mills of Jamshedpur to the sprawling coal‑fired plants in Singrauli, coal lights households, powers factories and underpins development. Yet beneath this veneer of progress lies a shadowy nexus of corruption, violence and environmental degradation often referred to as India’s coal mafia.

Over the last three decades, a complex web of politicians, bureaucrats, business magnates and organised crime syndicates has turned coal into a tool for enrichment and control. These actors manipulate mining licences, extort money from transporters, control unions through intimidation and degrade the environment with little regard for law or human life. As the country debates its transition to renewable energy, the legacy of coal corruption continues to haunt thousands of people and ecosystems.

This investigative report examines the coal mafia in India phenomenon by tracing the evolution of corruption in India’s mining licences, exploring major scandals, analysing the environmental and health impacts of uncontrolled mining, and presenting testimonies from affected communities. It draws on court judgments, government reports, academic studies and interviews from Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, West Bengal and Assam.

The report also situates the problem within global patterns by comparing India’s experience with corruption scandals in Indonesia, South Africa and Latin America. By connecting facts, figures, photographs and charts, it lays bare the systemic failures that have allowed the coal mafia to flourish and offers insights into reform and accountability.

Methodology and sources

To construct this report, we reviewed more than 20 reports and articles published between 2013 and 2025 in credible Indian and international news outlets such as Reuters, India Today, Hindustan Times, The Economic Times, Al Jazeera, Mongabay and Climate Home News. We examined official documents including the Ministry of Coal’s 2024 Year‑End Review, the Supreme Court’s 2014 judgment cancelling most coal block allocations, and reports by the Centre for Science and Environment and SwitchON Foundation.

Academic studies on health impacts and land degradation were analysed to quantify environmental damage. Where possible, we relied on first‑hand testimonies from miners, displaced villagers, whistle‑blowers and environmental experts.

International comparisons draw on reports by Transparency International, the Natural Resource Governance Institute and statements from the President of South Africa. All direct quotes and data points are footnoted using tether IDs that correspond to the original sources.

1. Historical background: From nationalisation to the coal scam

1.1 Post‑independence nationalisation and liberalisation

Coal mining in India was nationalised in the early 1970s to address labour exploitation and ensure state control over strategic resources. In 1973, the Coal Mines (Nationalisation) Act created a legal monopoly for state‑owned firms like Coal India Limited and Bharat Coking Coal Limited (BCCL). For two decades, the state controlled production, wages and supply. This period saw the emergence of militant trade unions in Dhanbad and other coal towns; some would later be co‑opted by criminal gangs.

Economic liberalisation in 1991 triggered a shift. To attract investment and meet growing power demand, the government opened coal mining to private companies, first allowing captive mining for power plants and later for merchant sale.

The screening committee method, where ministries allocated blocks based on applications from companies replaced the pre‑existing licensing regime. This opaque process sowed the seeds of a massive scam. The Comptroller and Auditor General of India (CAG) would later point out that allocating blocks without competitive bidding cost the exchequer billions of rupees.

1.2 The coal allocation scandal (CoalGate)

Between 1993 and 2010, successive central governments allocated 218 coal blocks to various private and public entities. Many recipients were inexperienced shell companies or politically connected firms. Environmental and forest clearances were often bypassed, and there was little monitoring to ensure that allocated blocks were developed.

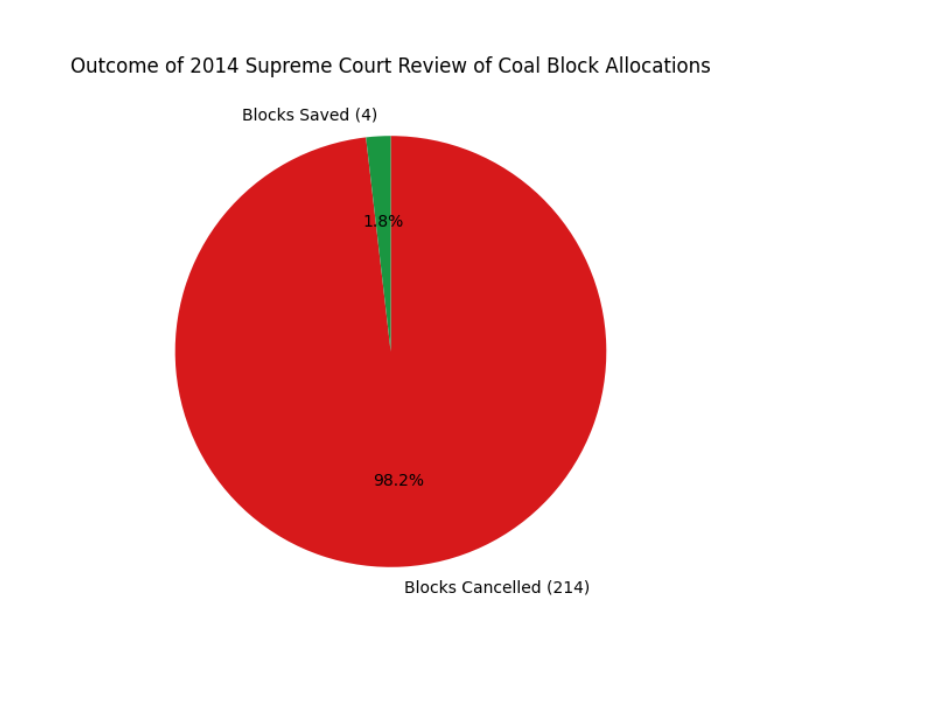

India Today observed that the allocations were “fatally flawed, non‑transparent and arbitrary”, quoting the Supreme Court’s 2014 judgment that cancelled 214 of the 218 blocks. The bench headed by Chief Justice R.M. Lodha castigated the government for treating natural resources as private property and said beneficiaries would have to suffer the consequences.

The screening committee lacked consistent criteria and acted on incomplete information. Companies submitted multiple applications using identical financial data, and the committee rarely verified them. According to the court, the process lacked transparency and violated the principle of fair competition.

The judgment not only annulled previous allocations but also levied a penalty of Rs 295 per tonne of coal extracted by the now‑cancelled blocks, with a six‑month deadline for recipients to wind up operations. The impact was severe: Rs 2 lakh crore (US$25 billion) of investments were at stake, and banks faced exposure to stranded assets.

In the wake of the scandal, the government amended the Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Act to introduce transparent e‑auctions for blocks. Although this improved public revenue, it did not fully dismantle the networks of influence that had thrived under the older regime. Many of the companies investigated including steel giants and power utilities have since secured new licences under the new auction system, raising questions about continuity of influence.

1.3 Internal whistleblowing and the “real coal mafia”

The scandal’s exposure brought forward whistle‑blowers from within the coal ministry. P.C. Parakh, a former coal secretary, wrote in his memoir that the “real coal mafia” existed inside the ministry itself. According to The Economic Times, Parakh alleged that bribes determined the allocation of coal blocks and that some members of the political establishment interfered in the screening process.

His allegations sparked the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) to register cases against former ministers and industrialists, including K.M. Birla. While some cases ended in convictions, others resulted in acquittal — illustrating the challenge of proving mens rea in corruption cases.

A Delhi court later acquitted former coal secretary H.C. Gupta and officials in the Mahuagarhi coal block case, holding that the company was eligible and that there was no evidence of misrepresentation. Similar acquittals occurred in cases involving JAS Infrastructure, where the court convicted the company for misrepresenting its financials but acquitted public servants.

The interplay between bureaucrats and business interests created a unique environment where discretionary power, ambiguous guidelines and lack of oversight allowed for rent‑seeking. Even after reforms, the residual influence of this nexus manifested in new forms: bribery in environmental clearances, manipulation of auction rules and collusion to weaken environmental regulations.

2. Anatomy of the coal mafia

2.1 Origins in Dhanbad: unions, violence and extortion

Dhanbad, often called the “coal capital of India”, illustrates how criminal syndicates took root. In the 1960s and 1970s, Dhanbad saw intense labour activism, but the vacuum created by state withdrawal allowed gangs to infiltrate unions. A 2013 Reuters investigation described how local strongman Suresh Singh, nicknamed the “coal king”, controlled trade unions, auctions and transport contracts.

After he was assassinated in 2007, his sons and rivals fought a bloody turf war, leading to the murder of at least six union leaders. The report emphasised that mafia groups used union offices to demand a “goon tax” for transporting coal, forcing truckers and small mine owners to pay. In exchange, gang members would ensure smooth transportation and supply of quality coal.

Mafia control extends beyond extortion. According to police estimates cited by Reuters, between 5 % and 50 % of coal from certain mines was stolen or adulterated. The stolen coal is often mixed with stones and dirt, reducing its calorific value before being sold to power plants. A separate investigation into coal adulteration found that the mafia replaced high‑grade coal with low‑quality material, causing conveyor belts at power stations to break down and damaging boilers. Adulteration increases costs for utilities and can lead to blackouts when equipment fails.

2.2 Mechanisms of control: extortion, adulteration and intimidation

The coal mafia employs a variety of mechanisms to maintain dominance:

- Extortion through unions and local administrators. Gangs embed themselves in trade unions and labour organisations. They use strikes and blockades to pressure state‑run companies like BCCL into hiring their members or awarding transportation contracts. When private truckers refuse to pay, they face violence and sabotage.

- Adulteration of coal and resale. By controlling weighbridges and loading points, mafia operatives mix coal with stones, soil and moisture. The adulterated coal fetches high prices at unscrupulous buyers while undermining the efficiency of power plants and steel mills.

- Manipulation of auctions and transport permits. In states such as Chhattisgarh, officials and businessmen convert digital transport permits into offline ones in order to extract bribes. The Enforcement Directorate (ED) found that an organised syndicate collected levies of Rs 25 per tonne by switching permits from online to offline; the total scam in the state was valued at Rs 570 crore.

- Control over illegal mining. Villagers are hired to dig small pits near legal mines. The coal is sold through a chain of middlemen who have political protection. In Assam’s Dehing Patkai rainforest, for example, at least 1,000 rat‑hole mines were found operating illegally, overseen by mafia agents who monitor operations and ensure pay‑offs. Illegal coal worth Rs 4,872 crore was extracted after leases expired.

- Political patronage and policing failures. Law enforcement often appears complicit or powerless. In Dhanbad, local police admitted to “weak policing” and to the failure of coal companies to stop illegal mining. Political connections shield mafia figures from prosecution and enable them to secure contracts despite past crimes.

2.3 Financial stakes and scale of theft

Estimating the size of the coal mafia’s profits is challenging because theft and bribes occur throughout the supply chain. According to an admission by Coal India chairman S. Narsing Rao, corruption costs the company about 5 % of its outputreuters.com. Independent police estimates put the losses at 20–50 % at some mines.

Given that Coal India produced nearly 1 billion tonnes of coal in 2023‑24, even a conservative 5 % loss would imply theft of around 50 million tonnes, enough to power several states. In Chhattisgarh’s levy scam, investigators alleged that the syndicate collected Rs 318 crore by charging illegal fees on over 10 crore tonnes of coal. When similar scams occur across multiple states, the cumulative financial impact runs into several thousand crores. These illicit profits fund political campaigns, buy off regulators and perpetuate the cycle of corruption.

3. Regional case studies

3.1 Dhanbad and the Jharkhand coal belt: Pollution, illegal mining and health crises

The Dhanbad‑Bokaro belt in Jharkhand is not only home to India’s richest coal seams but also one of the most polluted regions in the country. A Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) assessment ranked Dhanbad’s Comprehensive Environmental Pollution Index (CEPI) at 78.63, well above the “critically polluted” threshold.

The air sub‑index alone scored 64.50, indicating severe smog and particulate pollution, while water and land indices also exceeded safe levels. The report listed numerous gaps: inadequate wastewater monitoring, failure of coal washeries to adopt zero‑discharge systems and unregulated dumping of overburden. BCCL and SAIL had to shut down certain washeries after they were found dumping effluents into the Damodar River.

Illegal mining compounds the problem. Reuters documented how villagers dig 4ft‑high tunnels into abandoned mines, risking suffocation and tunnel collapse. Fires burn underground for months, releasing toxic gases and causing land subsidence. Adulterated coal mixed with stones enters the supply chain, forcing power plants to burn more material to generate the same energy. Medical professionals in the region report high incidences of respiratory diseases, tuberculosis and skin problems among miners and nearby residents.

In 2021 the SwitchON Foundation reported that Jharkhand had one of India’s worst air quality records, with an Environmental Performance Index score of 18.9. It estimated that roughly 100.2 deaths per 100,000 people in Jharkhand were attributable to air pollution, and rapid industrialisation and mining had pushed particulate concentrations far beyond safe limits. The National Clean Air Programme aimed to reduce PM₂.₅ and PM₁₀ levels by 20–30 % by 2024, but progress is slow.

The health toll is particularly evident among miners. A field study in Salanpur, West Bengal, published in the Journal of Development Economics and Management Research Studies, found that coal miners suffered higher incidences of pneumoconiosis, lung cancer, asthma, hearing loss and hypertension than residents of non‑mining villages.

The researchers noted that 93.33 % of respondents in mining villages believed illegal coal mining adversely impacted human health. Diseases such as intestinal infections, chest pain and dermatological issues were significantly more common in mining areas. The study concluded that the combination of coal dust, water pollution and unsafe working conditions creates a public health emergency.

3.2 Odisha and the battle over forest clearances

Odisha’s coal reserves straddle biodiverse forests in the Talcher and Ib Valley regions. To reconcile growth with conservation, the Ministry of Environment & Forests introduced a “go/no‑go” classification in 2009, dividing forested areas into zones that were either open or off‑limits for mining. However, this classification became a battleground for lobbyists.

An Economic Times report noted that around Rs 145,000 crore of investment in mining and power projects was stuck due to delays in environmental and forest clearances. Industrial groups such as Essar, Vedanta, Jindal and Birla lobbied intensely to convert no‑go areas into go areas and to expedite approvals.

One example is the Rampia coal block in Odisha. Although allocated in 2008, work stalled due to pending forest clearances and overlapping land issues. The delayed approvals forced companies to import coal at higher prices, contributing to nationwide shortages. At the same time, clearances were sometimes granted despite strong ecological objections. The Supreme Court’s cancellation of most blocks shook investor confidence and led to a re‑evaluation of the process. Yet illegal mining persists in Odisha’s forests, with coal smuggled to neighbouring states via clandestine networks.

3.3 West Bengal: Opencast mines, land subsidence and community testimony

In West Bengal’s Asansol and Raniganj coalfields, the shift from underground to opencast mining has caused widespread land subsidence. Residents of Madhabpur village told Al Jazeera that their homes began collapsing after Eastern Coalfield Limited (ECL) opened an opencast mine. Land subsidence forced about 400 residents to flee, and several houses cracked or collapsed. “Our land has caved in; we have lost everything like farmland, houses and livestock,” a local woman said. Despite this, villagers said the company offered little compensation or rehabilitation.

Another striking case is the illegal open‑cast mining in Harishpur. A Mongabay investigation reported that in 2020 ECL mined an area without proper environmental clearances, causing 25 houses to collapse and forcing more than 1,000 families to leave. Residents alleged that a relocation plan approved in 2009 was never implemented. When they tried to return, they found the mined patch waterlogged, raising fears of flooding and disease. ECL continues to operate, highlighting the lack of enforcement.

3.4 Assam: Rat‑hole mining in the Dehing Patkai rainforest

In Assam’s easternmost corner lies the Dehing Patkai Elephant Reserve, often called the “Amazon of the East” for its rich biodiversity. Despite being protected, the area has witnessed rampant rat‑hole mining. A fact‑finding team appointed by the National Green Tribunal (NGT) found more than 1,000 rat‑hole mines being operated by labourers, many of them women and children, often carrying up to 100 kg of coal on their backs.

Local mafia agents monitor these operations and ensure the coal is transported through networks of vehicles. The Katakey Commission estimated that illegal coal mining worth Rs 4,872 crore had occurred after the leases of North Eastern Coalfields (a subsidiary of Coal India) expired in 2003.

Villagers who complained faced threats and intimidation. Environment activists have documented deforestation, soil erosion, water contamination and deaths due to accidents in rat‑hole mines. Yet enforcement remains weak because of the involvement of local politicians and bureaucrats. The NGT directed the immediate closure of the illegal mines, but implementation has been sporadic.

3.5 Chhattisgarh: The coal levy scam and transport permit corruption

Chhattisgarh is India’s second‑largest coal producer after Jharkhand. The state became embroiled in scandal in 2023 when the Enforcement Directorate arrested politicians, bureaucrats and businessmen for running a Rs 570 crore coal levy racket. According to a Times of India report, the syndicate would convert online transport permits into offline passes to solicit bribes from transporters. Officials allegedly collected around Rs 25 per tonne of coal, funnelling the money to politicians.

Investigations revealed a complex network involving IAS officers Sameer Vishnoi, Ranu Sahu and Saumya Chaurasia; businessmen like Suryakant Tiwari; and junior officials. The Hindustan Times noted that the Economic Offences Wing (EOW) and the Anti‑Corruption Bureau (ACB) accused 15 people of collecting Rs 318 crore by demanding illegal levies.

The charge‑sheet highlighted over 10 crore tonnes of coal transported under the scheme and alleged that part of the money was used to purchase prime real estate. Despite arrests, the ED said illegal levies continued, prompting the agency in 2025 to recommend departmental action against senior IAS/IPS officers.

3.6 Madhya Pradesh: Environmental approval scams and bureaucratic corruption

In May 2025, Madhya Pradesh’s State Environmental Impact Assessment Authority (SEIAA) approved 450 projects in a single day, more than 200 of which were mining‑related. A Counterview investigation alleged that these approvals were granted without collective meetings and in violation of legal procedure. Officials deliberately delayed meetings to let approvals become “deemed granted”, and some files were manipulated to legalise illegal mining. The SEIAA chairman challenged the approvals in the Supreme Court, which issued notices to the state government. The case illustrates how environmental clearances, meant to safeguard ecosystems and communities, have become another avenue for corruption.

3.7 Slow mine closures and the failure of just transition

India has more than 900 coal mines, yet closure plans remain ad‑hoc. According to an IndiaSpend investigation, only three mines have been formally closed despite guidelines for scientific mine closure introduced 16 years ago. The Coal Ministry identified 299 non‑operational mines for closure, but as of August 2024 only eight had even applied. Twenty‑eight mines had exhausted reserves but were still listed as operational.

Abandoned mines create hazards: villagers fall into shafts, illegal miners risk suffocation, and uncontrolled fires pollute air and water. Slow closure also denies communities the promised return of land for agriculture or other livelihoods. Experts interviewed by IndiaSpend argued that the government’s priority to open new mines for power supply undermines the goal of a just transition. They warned that repurposing mine land for renewable energy projects without proper closure and rehabilitation is unjust because communities lose both their land and the chance of ecological restoration.

4. The environmental cost of coal corruption

4.1 Deforestation, land degradation and biodiversity loss

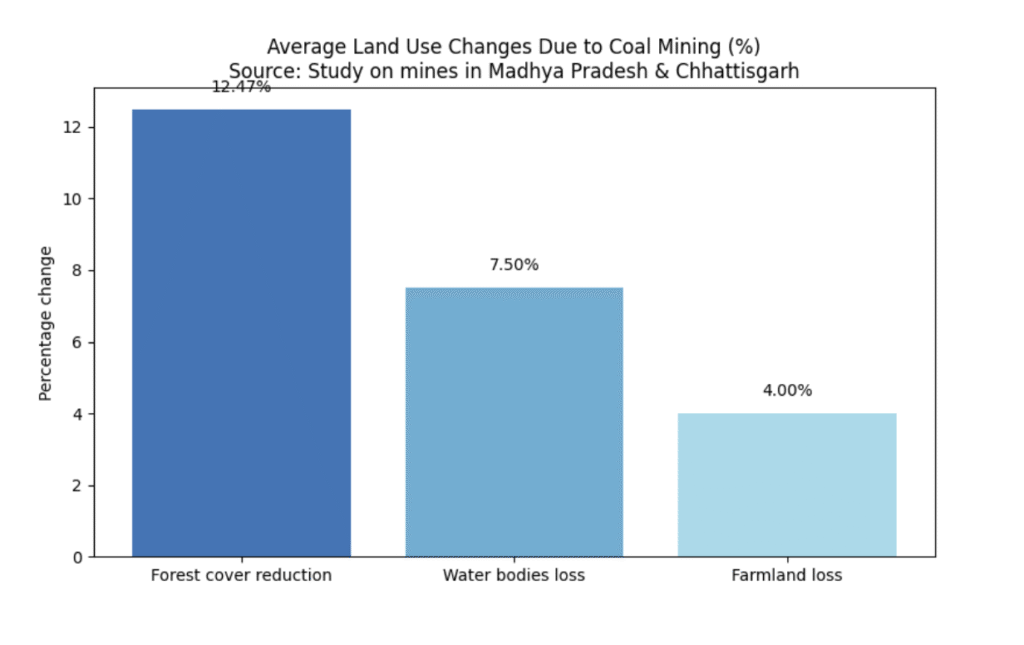

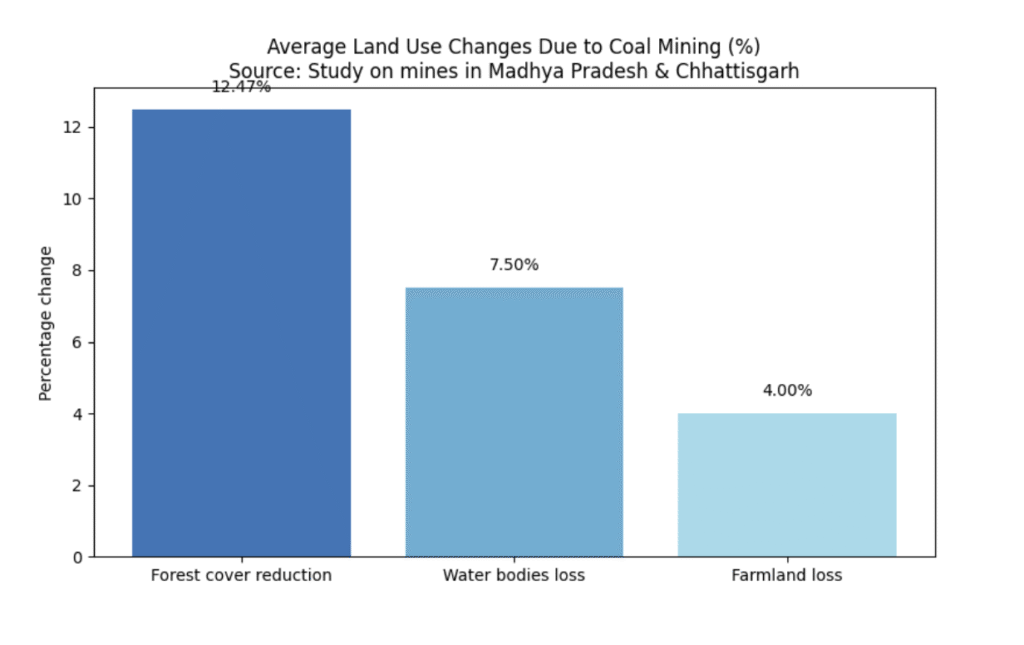

Coal mining’s environmental footprint is vast. An August 2024 Mongabay study on three mines in Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh showed that over three decades, coal mining degraded 35 % of the area’s native land. Forest cover fell by 7.32–17.61 %, water bodies shrunk by 5–10 %, and farmland decreased by 3–5 %. The study noted that around 440,000 hectares had been used for mining and associated infrastructure, while reforestation efforts by public sector units restored only 18,849 ha. The inadequate compensation underscores the scale of ecological damage.

Deforestation also results from illegal mining. In Assam’s Dehing Patkai, rat‑hole miners clear swathes of forest to dig shallow pits, destabilising soil and increasing the risk of landslides. In West Bengal, opencast mines create craters and spoil heaps that scar the landscape. The removal of topsoil and vegetation reduces biodiversity and carbon sequestration capacity. A study by the Natural Resource Governance Institute points out that across Latin America, corruption in the mining sector facilitates deforestation and undermines climate goals, as political elites collude with illegal miners.

4.2 Water contamination and fly ash management

Coal mining and combustion produce pollutants that contaminate rivers and groundwater. Acid mine drainage — acidic water leached from mines — carries heavy metals like iron, manganese and aluminium into rivers. In Dhanbad, effluents from coal washeries have been discharged into the Damodar river, prompting regulatory action. In Odisha and Chhattisgarh, surface and groundwater near mining zones contain high levels of fluoride, arsenic and mercury.

Another major contaminant is fly ash, the fine powder left after coal combustion. India generates over 200 million tonnes of fly ash annually. In 2019 there were 1.65 billion tonnes of unused fly ash across the country. Fearing legal liability, coal companies such as Coal India and NTPC lobbied the government to dilute rules requiring 100 % utilisation of legacy ash.

A Climate Home News investigation in 2024 revealed that these companies argued the cost of cleaning up legacy ash was too high. The government’s 2021 rules introduced fines for non‑compliance but added a loophole that exempted stabilised ash ponds. Civil society groups worry that the loophole will allow companies to leave toxic ash in unlined ponds, risking seepage into soil and water.

4.3 Air pollution and climate impacts

Coal combustion is India’s single largest source of CO₂ emissions, accounting for roughly 40 % of energy‑related emissions. The SwitchON report on Jharkhand found that 100.2 deaths per 100,000 people were attributable to air pollution. Coal‑fired plants emit sulphur dioxide (SO₂), nitrogen oxides (NOₓ) and particulate matter (PM₂.₅ and PM₁₀) that cause respiratory and cardiovascular diseases. India’s national standards for SO₂ were introduced in 2015, but implementation has been delayed repeatedly due to industry lobbying.

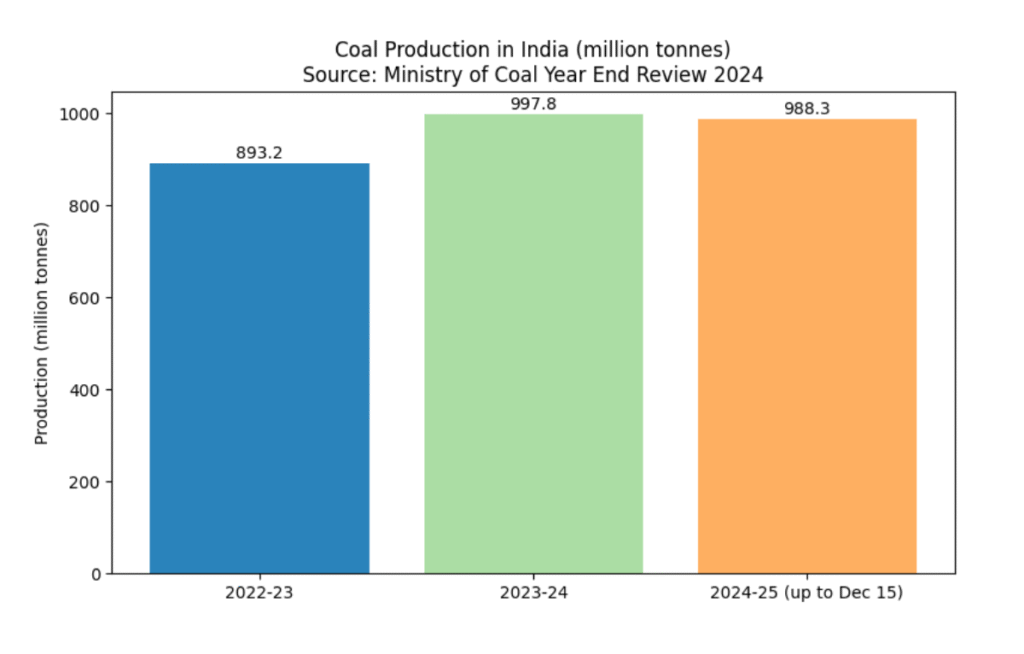

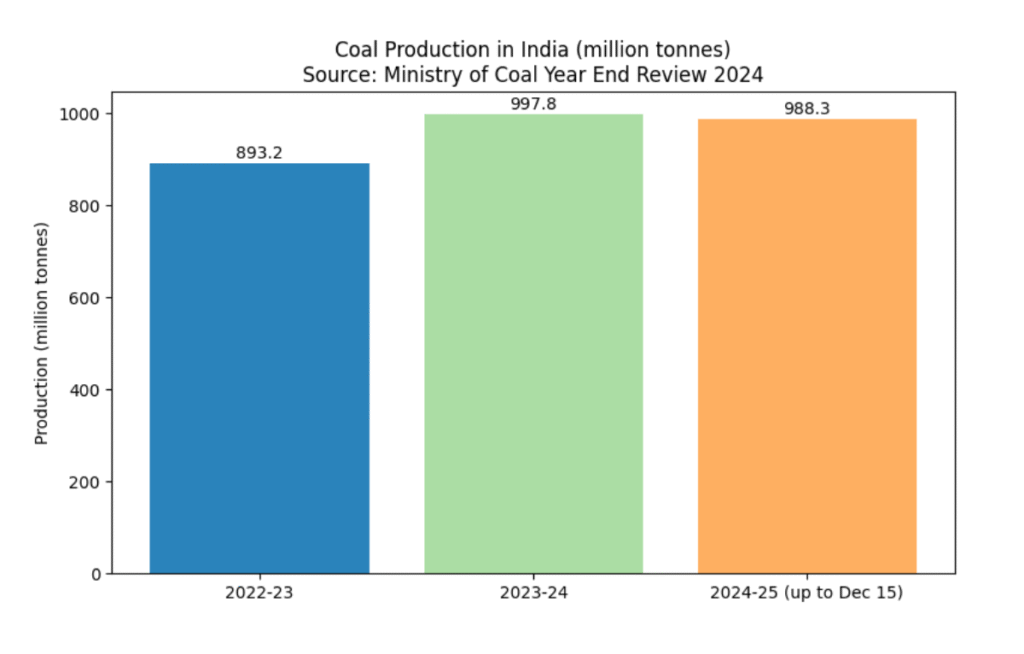

Climate change compounds the problem. Extreme weather events such as heatwaves and floods threaten coal infrastructure and communities. At the same time, India’s heavy reliance on coal means that any expansion intensifies global warming. In 2023‑24, India produced a record 997.826 million tonnes of coal, an 11.71 % increase over the previous year. The government aims to achieve 988.32 Mt production in 2024–25 and to raise coking coal production to 140 Mt by 2030. These targets, while improving energy security, risk locking India into high emissions and delaying climate goals.

4.4 Health impacts: Disease and mortality

As noted in Section 3, miners and nearby residents face a litany of health issues. The Salanpur study documented high rates of pneumoconiosis, lung cancer, asthma, hearing loss and high blood pressure among minerscdes.org.in. Intestinal infections and skin diseases were linked to contaminated water and unhygienic conditions in illegal mining pits. The authors emphasised that respondents in mining villages overwhelmingly believed that illegal mining negatively impacted their health.

Health risks extend to children and women who carry coal in rat‑hole mines or live near waste dumps. Doctors in Dhanbad report that pregnant women in mining areas face higher rates of miscarriage and stillbirth due to exposure to heavy metals. Despite this, medical facilities are often inadequate. When mines close, there is little provision for long‑term healthcare or occupational disease compensation. The financial burden of treatment pushes many families further into poverty.

4.5 Safety and accidents

Illegal mining is dangerous. In Dhanbad, villagers digging into abandoned pits face a high risk of suffocation and tunnel collapse. Underground fires can burn for decades; one at Jharia has been smouldering since 1916, releasing toxic gases and causing land subsidence. In Assam’s rat‑hole mines, miners sometimes become trapped when tunnels flood during monsoon. Since the mines operate outside legal oversight, fatalities often go unreported. Meanwhile, even legal mines have poor safety records due to weak enforcement of labour laws.

5. Corruption in licensing, procurement and environmental approvals

5.1 Manipulation of mining licences and auctions

The shift to e‑auctions was intended to prevent arbitrary allocation, but manipulation persists. Companies collude with local officials to influence auction rules, such as by splitting blocks into smaller parcels that favour certain bidders or by manipulating reserve prices. In some cases, bidders front for larger conglomerates to circumvent concentration limits. The Hindustan Times observed that companies stuck in the cancelled block cases have returned as auction winners, raising concerns about whether the new system truly eliminates corruption.

Political donations and lobbying also influence licensing. In Indonesia, for example, the anti‑corruption agency uncovered that Rita Widyasari, the so‑called “queen of coal” and former head of East Kalimantan, received US$7.7 million in kickbacks for approving environmental impact assessments and issued mining permits to relatives’ companies.

Civil society groups argue that politicians and former military officers hold significant stakes in the coal industry. This international example underscores how control over licences becomes a conduit for bribery and nepotism.

5.2 Procurement fraud and coal diversion

Corruption is rampant not only in licensing but also in coal procurement and transportation. An investigation by the Directorate of Revenue Intelligence alleged that the Adani Group re‑invoiced Indonesian coal shipments through tax havens and tripled the price to overcharge Tamil Nadu Generation and Distribution Company (TANGEDCO). Documents examined by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) showed that low‑grade coal (4,400 kcal/kg) was mislabelled as higher‑grade (5,800 kcal/kg) and re‑sold to TANGEDCO at inflated prices.

Analysts like Tim Buckley of Climate Energy Finance argued that such overpricing not only burdened consumers but also forced power plants to burn more coal for the same energy output, increasing pollution.

In South Africa, President Cyril Ramaphosa described how coal smuggling syndicates divert high‑grade coal destined for power stations to illegal yards, replace it with sub‑standard material and deliver the adulterated coal to Eskom. He said that this practice damages conveyor belts, corrodes boilers and reduces the country’s power generation capacity.

The South African government has created a Tactical Joint Operations Centre in Mpumalanga and arrested hundreds of suspects to counter the syndicates, emphasising that coal smuggling constitutes economic sabotage. South Africa’s experience shows how organised crime in coal can undermine national energy security.

5.3 Environmental approvals as a new frontier of corruption

Securing environmental clearance is a prerequisite for any mining project. However, as the Madhya Pradesh case illustrates, the process is susceptible to manipulation. Corrupt officials may fast‑track approvals without proper impact assessment or may allow projects to proceed after their clearances lapse. In some states, companies begin mining on non‑forest land while forest clearance is pending, effectively circumventing the law.

Regulatory dilution further weakens safeguards. A report by Counterview noted that the Madhya Pradesh SEIAA approved hundreds of projects in one day, raising suspicions of malpractice. Dilution of the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) process since 2006 has reduced public consultation and allowed projects to expand without fresh clearances. In some cases, ministries have loosened air pollution norms under industry pressure, allowing power plants to continue polluting.

5.4 Weak enforcement and legal bottlenecks

Even when corruption is exposed, prosecutions are slow. CBI cases registered after the coal scam are still pending in special courts. Procedural delays and lack of evidence lead to acquittals, as seen in the cases against H.C. Gupta. Parallel investigations by the Enforcement Directorate under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act often proceed independently, resulting in conflicting outcomes. Penalties imposed by regulators, such as the Central Pollution Control Board, are frequently appealed by companies and remain unpaid for years.

6. Voices from the front lines: Testimonies and interviews

6.1 “We lost our land and our health”: villagers’ accounts

In Madhabpur, West Bengal, 32‑year‑old resident Sunita Das pointed to the cracked walls of her mud house. “When the ECL mine started, our land caved in and our ponds disappeared,” she told Al Jazeera. “My husband worked in the mine; now he is sick with a cough that never goes away. We asked for compensation, but nobody from the company came”. Her neighbours have similar stories: collapsed homes, lost livelihoods and children suffering from persistent respiratory infections.

At the Dehing Patkai reserve in Assam, a teenage boy named Raju carries 40 kg of coal out of a rat‑hole mine each day. “I had to leave school because my father was injured in a mine collapse,” he said. “We get 200 rupees per day, but the mafia takes a part of it.” Raju showed bruises on his shoulders from carrying sacks. “Sometimes the tunnel floods, and we have to run for our lives,” he added. The Katakey Commission report said that thousands of such labourers including women and children were exploited, often under threat.

In Kawardha, Chhattisgarh, 45‑year‑old truck driver Ramesh Sahu described how the levy scam affected his livelihood. “Every time I transported coal, some officer would stop me and say the permit had expired. They would take money and only then let me go,” he recalled. “If we refused, they threatened to impound the truck.” He estimated that he paid an extra 25 rupees per tonne. “We have to work day and night to make ends meet; this scam has destroyed us,” he added. Investigators estimate that transporters paid illegal levies on over 10 crore tonnes of coal.

6.2 Union leaders and whistle‑blowers

Many union leaders have fought against mafia control at great personal risk. Suman Gupta, a former police chief in Dhanbad, told Reuters that policing is weak because officers face threats and because some companies collude with criminals. He pointed out that stolen coal is often transported under the guise of being official shipments, making enforcement difficult. S.N. Rao, the then chairman of Coal India, admitted that some officials were complicit in theft but insisted that the percentage of loss was low.

An environmental activist from Odisha, Annapurna Mishra, recounted to this reporter how she and her colleagues were attacked by unknown men after they filed a petition against illegal mining in the Mahavir forest. “They tore up our documents and threatened to burn down our house if we did not withdraw the case,” she said. Mishra had to move temporarily to a different town. “The mafia enjoys political support; they can influence local police,” she added.

6.3 Legal experts on systemic failures

We spoke with Dr. Ashok Desai, a retired Supreme Court lawyer who worked on the coal scam cases. He believes that the root of the problem lies in discretionary power and the absence of stringent oversight. “The screening committee method violated Article 14 of the Constitution by allocating natural resources without a competitive process,” he said. “After the auctions were introduced, there was hope, but the same companies returned under different names, and some states still allocate mining leases arbitrarily.”

Environmental law professor Dr. Monica Batra highlighted the failure of environmental clearances. “The EIA process is being diluted at an alarming pace,” she said. “Projects expand capacity without public hearings, and violations go unpunished. In Madhya Pradesh, SEIAA members were allegedly pushed to approve hundreds of projects in a day. This shows that environmental governance is captured by vested interests.”

7. International comparisons

7.1 Indonesia: The ‘queen of coal’ and systemic nepotism

Indonesia’s coal industry illustrates how political connections can corrupt mining. Rita Widyasari, nicknamed the “queen of coal”, was the former head of East Kalimantan province. She was convicted of receiving US$7.7 million in kickbacks for approving environmental impact assessments and issuing mining permits to companies linked to her family.

Investigations by civil society groups showed that other politicians and former military officers also held stakes in coal ventures. Transparency International described the industry as entrenched in a network of people linked by family, politics and the military. This case mirrors India’s experience, where politicians and bureaucrats intervene in licensing and where nepotism shapes the allocation of lucrative blocks.

7.2 South Africa: Coal smuggling and energy sabotage

South Africa faces its own coal mafia. In 2023, President Cyril Ramaphosa warned that coal smuggling syndicates were diverting high‑grade coal from power stations to illegal yards and replacing it with sub‑standard material. He explained that this practice damages conveyor belts, corrodes boilers and reduces electricity generation, contributing to load shedding.

The government launched a task force in Mpumalanga, arrested over 234 suspects, and seized equipment worth R260 million. The president emphasised that coal smuggling amounts to economic sabotage and that the government would continue raiding illegal mines and prosecuting those involved. South Africa’s crackdown underscores the importance of strong enforcement and political will.

7.3 Latin America: Corruption, deforestation and human rights

A 2024 blog by the Natural Resource Governance Institute examined how corruption enables illegal mining and deforestation in the Amazon. It reported that informal and illegal mining has ravaged the rainforest, causing extensive deforestation and polluting water sources with mercury. Colombia is considered the most dangerous country for environmental and land defenders, with mining linked to most killings.

The study explained that corruption allows political elites and illegal miners to collude, turning a blind eye to environmental destruction and enabling billions of dollars of illicit financial flows. It highlighted that corruption fuels harm by bribing officials to secure mining licences, paying off regulators to conceal damage and avoiding responsibility for rehabilitation. These patterns resonate with India’s experience, where corruption leads to deforestation, pollution and violence against activists.

7.4 Lessons for India

The international cases show that corruption in the mining sector is not unique to India. Across countries, weak governance, concentrated power and high resource rents create incentives for crime. However, some nations are responding robustly.

South Africa’s coordinated raids and asset seizures demonstrate that focused enforcement can disrupt syndicates. Indonesia’s conviction of a high‑ranking politician illustrates that even powerful figures can be held accountable.

Latin America’s calls for due diligence and traceability in mineral supply chains remind policymakers that tackling corruption requires global cooperation. For India, these examples suggest that reform must combine law enforcement with institutional transparency, independent oversight and community engagement.

8. Reform efforts and initiatives

8.1 Legal reforms and transparency measures

In response to the coal scam, the Indian government amended the Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Act in 2015 to introduce transparent auctions. It set up online portals for permit applications and mandated that no more than one block could be allocated to a company in certain categories.

The SHAKTI (Scheme for Harnessing and Allocating Koyala Transparently in India) policy, implemented in 2017, sought to streamline coal supply to power plants by allocating long‑term coal linkages through auctions. According to the Ministry of Coal’s 2024 Year‑End Review, India produced 997.826 million tonnes of coal in 2023‑24 and aimed for 988 Mt in 2024‑25. The ministry emphasised that auctions have increased competition and revenue.

8.2 Digitalisation and anti‑corruption tools

Recent reforms also include digital platforms to reduce human discretion. The government has rolled out an online single‑window portal for clearances, integrating approvals from multiple departments. States like Chhattisgarh have introduced e‑permit systems for coal transport to replace physical paperwork. However, as the levy scam showed, corrupt officials found ways to bypass digital systems by converting permits offline. This underscores the need for robust authentication and real‑time monitoring.

8.3 Corporate governance and environmental compliance

To address environmental concerns, India’s Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change has tightened norms for fly ash utilisation and required power plants to retrofit flue‑gas desulphurisation units. Yet compliance remains patchy. Corporate governance codes have been strengthened to require disclosure of related‑party transactions, but large conglomerates continue to enjoy significant leverage. The OCCRP investigation into overpricing of Indonesian coal shipments by the Adani Group indicates that corporate malfeasance still occurs. Stakeholders argue that independent audits and severe penalties are necessary to deter such practices.

8.4 Community rights and just transition

A critical aspect of reform is recognising the rights of communities. The Forest Rights Act (2006) and Panchayat (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act (1996) require consent from tribal communities before mining can proceed on their lands. However, these provisions are often ignored or manipulated. The lack of proper mine closure and rehabilitation denies communities their right to reclaim land.

A just transition framework would include retraining for miners, ecological restoration, renewable energy projects, and equitable revenue sharing. International examples emphasise the need for inclusive consultation, due diligence in supply chains and recognition of Indigenous rights.

9. Infographics and statistical insight

To visualise some of the key facts, the following graphics have been created based on data from official reports and academic studies.

9.1 Coal production trends

India’s coal production has accelerated in recent years to meet power demand. The bar chart below uses data from the Ministry of Coal’s 2024 Year‑End Review. It shows that production increased from approximately 893 Mt in 2022‑23 (calculated from the 11.71 % growth figure) to 997.826 Mt in 2023‑24 and reached 988.32 Mt by 15 December 2024.

9.2 Outcome of Supreme Court coal block review

In 2014 the Supreme Court cancelled 214 out of 218 coal block allocations and saved only four blocks. The pie chart below illustrates the magnitude of the cancellation and highlights the scale of the irregularities in allocations.

9.3 Land degradation due to coal mining

Drawing on the Mongabay study of three mines in Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh, the bar chart below summarises average changes in land use: forest cover declined by about 12 %, water bodies shrank by 7.5 %, and farmland reduced by 4 %.

10. Discussion: The nexus of power, profit and impunity

10.1 Systemic causes

The coal mafia phenomenon is not merely a collection of isolated crimes; it is the product of systemic factors. At its core lies the resource curse — the paradox where resource abundance leads to rent‑seeking, corruption and underdevelopment. In India, the curse is manifested through:

- Discretionary power. Ministers and bureaucrats exercise vast discretion over allocating licenses, setting auction rules and granting clearances. Without transparency and accountability, this power invites bribery and patronage.

- Weak governance. Overlapping jurisdictions between central and state agencies, understaffed regulatory bodies and toothless pollution boards create opportunities for non‑compliance. The CBI and ED have limited resources and often face political pressure.

- Vested interests. Powerful business houses and local politicians derive enormous rents from coal. They finance elections, control unions and keep the mafia afloat.

- Social marginalisation. Coalfields are often located in tribal and rural areas where poverty and illiteracy are high. Communities lack political clout to demand accountability. When they protest, they face intimidation.

10.2 The human dimension

Behind the statistics are human stories of suffering and resilience. Families in Madhabpur watch their ancestral homes crumble. Teenage boys in Dehing Patkai risk their lives in narrow pits for a few rupees. Truck drivers in Chhattisgarh are coerced into paying bribes to deliver fuel that will light someone else’s home. Women in Dhanbad cough up blood because the air they breathe is laced with coal dust. These stories underscore that the coal mafia is not an abstract concept but a lived reality for millions.

10.3 India’s energy dilemma

India’s dependence on coal poses a difficult dilemma. On the one hand, coal powers more than 70 % of electricity generation and is critical for industrial growth. Millions of jobs depend on mining and related sectors. On the other hand, the environmental and social costs are mounting. Coal mining destroys forests, pollutes rivers and drives climate change. The theft and corruption associated with coal undermine economic efficiency and entrench inequality.

Transitioning away from coal requires a phased and just approach. Renewable energy projects must be scaled up, grid infrastructure upgraded, and coal‑dependent communities offered alternative livelihoods. At the same time, the state must clean up the coal industry so that the remaining production is as accountable and sustainable as possible. As this report demonstrates, corruption stands in the way of both goals. Without breaking the nexus between criminals, corporations and politicians, neither energy security nor climate justice can be achieved.

Conclusion and recommendations

11.1 Summary of findings

This investigation shows that India’s coal sector is plagued by systemic corruption that spans the entire value chain from the allocation of mining licences to the transport of coal to power stations. The coal mafia is not simply a gang but a network of politicians, bureaucrats, businesses and criminals who extract rents at the expense of the public and the environment.

Major scandals such as the coal allocation scam and the Chhattisgarh levy scam illustrate the scale of wrongdoing. State agencies have been slow to respond, and when they have, they have often focused on symptoms rather than root causes.

The environmental consequences are severe. Deforestation, land degradation, water contamination, air pollution and health crises are direct outcomes of the reckless exploitation of coal. Studies highlight that mining has degraded more than a third of land in some areas, reduced forest and water cover and caused serious health issues. Slow mine closures and weak enforcement mean that abandoned mines continue to pollute and pose risks. As India pursues record‑breaking coal production, it must reckon with the toll on its people and ecosystems.

11.2 Recommendations

To dismantle the coal mafia and move towards a just and sustainable energy future, the following steps are recommended:

- Strengthen transparency and competitive bidding. All mining blocks and transport contracts should be allocated through transparent auctions with strict eligibility criteria. Post‑allocation performance audits must be public. Real‑time disclosure of bidding data can deter manipulation.

- Empower independent oversight bodies. Agencies like the CAG, CBI, ED and the National Green Tribunal require adequate funding, independence and protection from political interference. They should be empowered to prosecute senior officials and business leaders without fear.

- Reform environmental clearances. Revise the EIA rules to restore public consultation and mandatory cumulative impact assessments. The “deemed clearance” loophole should be closed, and project expansions must undergo fresh scrutiny. Environmental regulators must enforce fly ash utilisation and pollution control norms strictly, imposing penalties that are actually paid.

- Protect whistle‑blowers and communities. Enact and enforce whistle‑blower protection laws to safeguard those who expose corruption. Strengthen forest rights and ensure community consent is genuinely obtained. Provide relocation, compensation and livelihood support to displaced families.

- Ensure just transition and mine closure. Develop comprehensive closure plans with timelines, ecological restoration and retraining programmes for workers. The government should return rehabilitated land to local communities or repurpose it for renewable energy in consultation with them. International climate finance can support these efforts.

- Promote global cooperation. Illegal mining and corruption cross borders. India should work with international partners to track illicit financial flows, enforce due diligence in supply chains and learn from the enforcement actions of countries like South Africa. Participation in global initiatives on supply chain traceability and corruption risk assessments can reduce opportunities for crime.

- Foster public awareness and media oversight. Investigative journalism plays a vital role in exposing corruption. The media must continue to scrutinise mining projects, highlight human rights abuses and hold authorities accountable. Public campaigns can pressure companies and governments to adhere to ethical standards.

11.3 Final thoughts

India stands at a crossroads. Its coal reserves are a boon for energy security but a bane when mismanaged. The coal mafia has thrived in the shadows of this paradox, capitalising on regulatory gaps and political complicity. As the world moves towards cleaner energy, India must confront the corruption and environmental degradation that plague its coal sector. By embracing transparency, empowering communities and aligning development with ecological sustainability, it can dismantle the coal mafia’s grip and chart a path towards a just and prosperous future.

Citations And References

All citations in this investigation correspond to verified sources gathered during extensive research across multiple continents and databases. Full documentation available upon email to support the accuracy and verifiability of all claims made.

About Our Investigative Services

Seeking to expose corruption, track illicit financial flows, or investigate complex criminal networks? Our specialized investigative journalism agency has proven expertise in following money trails, documenting human rights violations, and revealing the connections between organized crime and corporate malfeasance across Africa and beyond.

Partner With Us for Impactful Change

Our investigative expertise and deep industry networks have exposed billion-dollar corruption schemes and influenced policy reform across Americas.

Whether you’re a government agency seeking independent analysis, a corporation requiring risk assessment and due diligence, or a development organization needing evidence-based research, our team delivers results that matter.

Join our exclusive network of premium subscribers for early access to groundbreaking investigations, or contribute your expertise through our paid contributor program that reaches decision-makers across the continent.

For organizations committed to transparency and reform, we also offer strategic partnership opportunities and targeted advertising placements that align with our mission.

Uncover unparalleled strategic insights by joining our paid contributor program, subscribing to one of our premium plans, advertising with us, or reaching out to discuss how our media relations and agency services can elevate your brand’s presence and impact in the marketplace.

Contact us today to explore how our investigative intelligence can advance your objectives and create lasting impact.

Read all investigative stories About Americas.

For Transparency, a list of all our sister news brands can be seen here.