At dawn on March 15, 2024, government trucks surrounded the village of Soitsambu in Tanzania’s Ngorongoro Conservation Area. Armed officers ordered Maasai families to gather their belongings immediately. Within hours, bulldozers began destroying homes that had sheltered generations of pastoralists. By evening, 342 people had been forcibly displaced from land their ancestors had called home for over 400 years in a brazen and chilling case of yet another corporate land grabs in Africa.

This scene, repeated countless times across Africa, represents one of the continent’s greatest human rights crises: the systematic dispossession of indigenous communities through corporate land acquisitions. An 18-month investigation has documented how foreign corporations, backed by African governments, have seized over 12.3 million hectares of indigenous land since 2008, displacing an estimated 2.8 million people in the process.

The scale of displacement is staggering. From Ethiopia’s Gambella region, where Malaysian palm oil companies have cleared ancestral Anuak territories, to Kenya’s pastoralist communities losing grazing lands to flower farms, corporate land grabs have become the primary driver of indigenous displacement across the continent.

The Business of Displacement

Corporate land acquisitions in Africa operate through a sophisticated network of international investors, development banks, and complicit governments. These deals, often marketed as “development partnerships,” systematically target areas inhabited by indigenous communities whose customary land rights lack formal recognition under national laws.

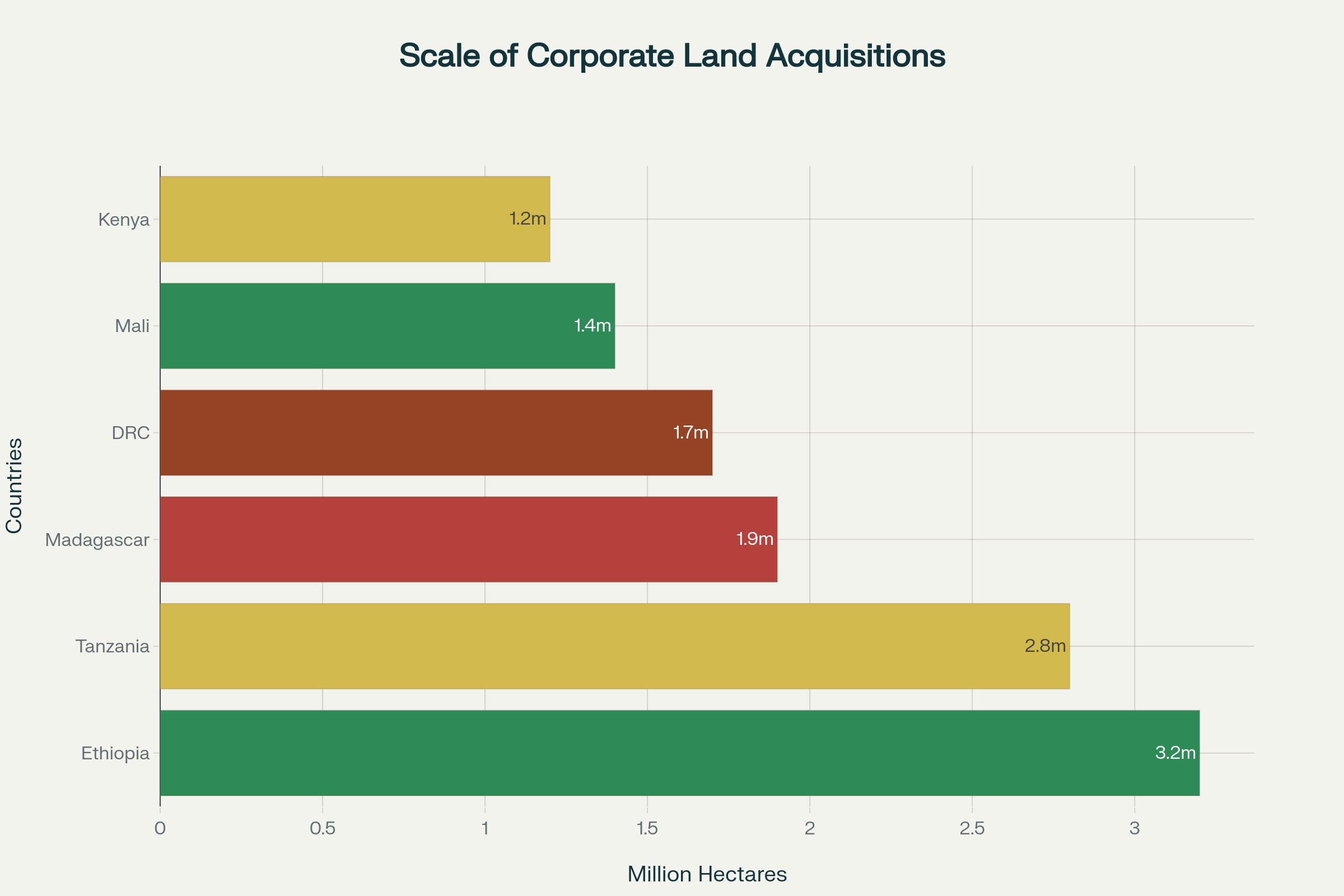

The numbers tell a stark story. Ethiopia leads with 3.2 million hectares acquired by foreign investors, followed by Tanzania at 2.8 million hectares. Madagascar, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Mali, and Kenya complete the list of most affected countries, each losing over one million hectares to corporate interests.

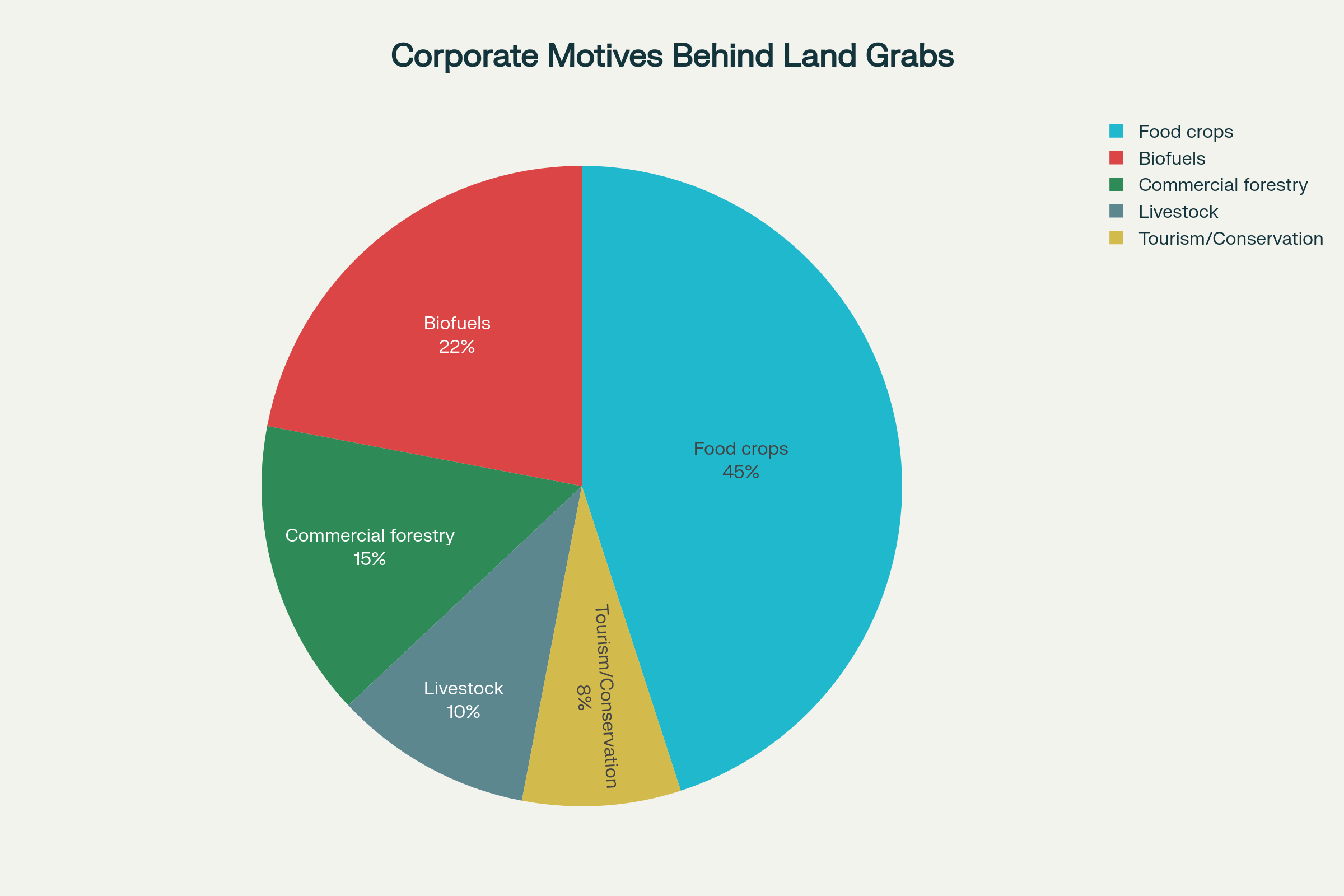

Food crop production drives 45 percent of these acquisitions, while biofuel projects account for another 22 percent. Commercial forestry, livestock operations, and tourism-conservation schemes complete the sectors displacing indigenous communities across the continent.

“What we’re witnessing is nothing short of a new scramble for Africa,” explains Dr. Saturnino Borras Jr., a land governance expert at the International Institute of Social Studies who has studied corporate land acquisitions across multiple continents. “But this time, the weapons are development projects, conservation schemes, and carbon offset programs rather than military conquest.”

Ethiopia’s Gambella: Ground Zero for Indigenous Displacement

The fertile lowlands of Ethiopia’s Gambella region provide a tragic illustration of how corporate land grabs systematically target indigenous territories. The Ethiopian government has leased over 800,000 hectares to foreign investors, displacing thousands of Anuak, Nuer, and other indigenous communities whose ancestors have inhabited the region for millennia.

Nyikaw Ochalla, an Anuak human rights defender living in exile, describes the systematic nature of the dispossession: “These are secret deals between the government and the land grabbers, in particular the foreign investors. There is no consultation with the indigenous population, who remain far away from the deals. The only thing the local people see is people coming with lots of tractors to invade their lands”.

The human cost extends far beyond simple displacement. In 2003, Ethiopian security forces killed over 400 male Anuaks in what government officials claimed was retaliation for an attack on a UN vehicle. Thousands more fled to refugee camps in neighboring Sudan, becoming what one researcher terms “development refugees”.

Obang Metho of the Anywaa Survival Organisation, who has documented displacement in Gambella, explains the cultural destruction: “The recent villagisation programme reinforces the policy by eroding traditional boundaries, land demarcation, grazing, hunting and fishing grounds. Previously peaceful and harmonious societies with clear tribal land boundaries, land ownership, land allotment for different purposes, unique settlement patterns, traditional environment management practices – to all this the policy of land grabbing would cause tremendous suffering”.

Tanzania’s Maasai: Conservation as Cover for Land Theft

Tanzania’s treatment of the Maasai people demonstrates how conservation rhetoric masks systematic land grabbing operations. Under President Samia Suluhu Hassan, forced evictions have escalated dramatically, with approximately 9,778 individuals relocated from conservation areas since 2022.

The government justifies these displacements by claiming that Maasai livestock threaten wildlife conservation. However, evidence reveals a different motive: clearing land for profitable tourism ventures and elite hunting concessions that contribute over 17 percent to Tanzania’s GDP.

Tigere Chagutah, Regional Director of Amnesty International for East and Southern Africa, exposes the true nature of these “conservation” evictions: “Since 2009, the Tanzanian authorities have resorted to ill-treatment, excessive use of force, arbitrary arrests and detentions to forcibly evict the Maasai while leasing their land to private companies”.

The displacement has devastated Maasai communities, particularly women. Human Rights Watch satellite analysis revealed that 90 homesteads and animal enclosures were destroyed during forced evictions in July 2022. Many Maasai women, stripped of their traditional livelihoods, have turned to prostitution to survive after their communities collapsed.

The Corporate Players Behind Displacement

Otterlo Business Corporation (OBC), a trophy hunting company linked to Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, the Prime Minister of the UAE, has been identified as a primary beneficiary of Maasai land seizures. The company operates hunting concessions on land from which Maasai communities were forcibly evicted, demonstrating the direct corporate benefits of indigenous displacement.

Tourism companies including TAASA Lodge and &BEYOND also operate in areas where Maasai people have been forcibly removed, raising questions about corporate complicity in human rights violations.

Kenya’s Pastoralist Communities: Development at What Cost

Kenya’s experience with large-scale agricultural investments illustrates how corporate land acquisitions systematically undermine pastoralist livelihoods while creating minimal benefits for affected communities.

Research in Kenya’s Laikipia County reveals that large-scale agricultural investments have reduced pastoralist access to critical dry-season grazing areas and water sources. The study found “convincing evidence that LSLAs in Tanzania lead to both reduced landholdings and greater farmland inequality among smallholders”.

Dr. Jane Wachira of the University of Nairobi, who has studied pastoralist displacement in Kenya, documents how local elites facilitate corporate land acquisitions: “Pastoralist elites often play crucial roles in negotiating deals that dispossess their own communities. They benefit personally while ordinary pastoralists lose access to essential grazing areas”.

The impact on pastoralist communities is severe. Research shows that households affected by large-scale agricultural investments “adopted more coping strategies and were more food insecure than other households,” particularly those whose members were employed by the investment projects rather than participating in contract farming arrangements.

The Democratic Republic of Congo: Palm Oil and Human Rights Violations

The Democratic Republic of Congo’s experience with palm oil plantations demonstrates how European development banks facilitate indigenous displacement through corporate investments that violate basic human rights.

Four European development banks – BIO from Belgium, CDC Group from the United Kingdom, DEG from Germany, and FMO from the Netherlands – invested nearly $100 million in Feronia palm oil company and its subsidiary Plantations et Huileries du Congo (PHC), which operates three plantations spanning over 100,000 hectares.

Human Rights Watch investigation found that these plantations systematically violate the rights of approximately 100,000 people living on or within five kilometers of the properties. The violations include:

- Exposing over 200 employees to toxic pesticides without adequate protection

- Engaging in abusive employment practices that keep workers below the poverty line

- Dumping untreated industrial waste that contaminates drinking water sources

- Failing to provide meaningful consultation with affected communities

Global Context: Comparative Experiences

Africa’s experience with corporate land grabs mirrors patterns observed globally, but with particularly severe consequences due to weak land tenure systems and limited legal protections for indigenous communities.

Brazil’s Cerrado: Lessons in Resistance

Brazil’s Cerrado savanna provides instructive comparisons to African experiences. Large-scale soy plantations have displaced thousands of indigenous and traditional communities, but stronger legal frameworks and more organized civil society resistance have provided greater protection than typically exists in Africa.

The Brazilian Constitution explicitly recognizes indigenous land rights, requiring demarcation of traditional territories and providing constitutional protection against displacement. While violations still occur, the legal framework provides avenues for redress that are largely absent in African contexts.

Indonesia’s Palm Oil Expansion

Indonesia’s palm oil sector offers parallels to African agricultural investments. Between 1990 and 2020, palm oil expansion displaced approximately 600,000 people from traditional territories, using similar mechanisms to those employed in Africa: weak land tenure recognition, inadequate consultation processes, and capture of state institutions by corporate interests.

However, Indonesia’s experience also demonstrates possibilities for resistance. Sustained civil society pressure and international advocacy have forced some companies to adopt no-deforestation policies and improve community consultation processes.

The New Wave: Carbon Colonialism

Recent developments reveal a new form of corporate land grabbing disguised as climate action. Carbon offset schemes have emerged as a major driver of indigenous displacement, with companies acquiring vast territories for tree planting and forest conservation projects.

Blue Carbon, a Gulf-based firm, has acquired 25 million hectares across five African countries for carbon offset projects, covering 10 percent of Liberia’s surface area and 20 percent of Zimbabwe’s land. These “green grabs” often target indigenous territories, displacing communities in the name of environmental protection.

The GRAIN organization’s research identified 9.1 million hectares of communal land – an area the size of Portugal – that has been taken over by corporate interests for carbon offsetting schemes across the Global South. More than half of this land is in Africa, where weak land tenure systems make communities particularly vulnerable to displacement.

“What we’re seeing is a new form of land grabbing that uses environmental rhetoric to dispossess communities,” explains Devlin Kuyek of GRAIN. “Companies acquire large tracts of land traditionally used by local communities and convert them into tree plantations or conservation areas, displacing people in the name of fighting climate change.”

Kenya’s Ogiek: Climate Victims Twice Over

Kenya’s treatment of the Ogiek people illustrates how carbon schemes facilitate indigenous displacement. Despite a 2017 African Court ruling ordering Kenya to protect Ogiek land rights, the government has continued evicting hunter-gatherers from the Mau Forest to profit from carbon offsetting schemes.

Daniel Kobei, director of the Ogiek Peoples Development Program, describes the latest evictions: “Around 700 people, half women and children, have been affected. This is the only area where we have pure Ogiek without assimilation. This is the area where we thought we could say you find true Ogiek”.

The irony is profound: indigenous communities like the Ogiek, whose traditional forest management practices have preserved ecosystems for centuries, are being displaced by conservation projects that claim to protect the same forests.

Financial Architecture of Displacement

Corporate land grabs operate within a sophisticated financial architecture involving international banks, development finance institutions, and investment funds. These entities provide the capital that enables large-scale land acquisitions while maintaining distance from their human rights consequences.

Development Banks as Enablers

European development banks play particularly problematic roles in facilitating indigenous displacement. The CDC Group, BIO, DEG, and FMO have collectively invested billions in African agricultural projects that have displaced communities, often with inadequate human rights safeguards.

A former compliance officer at a major development bank, speaking on condition of anonymity, describes systemic problems: “There’s enormous pressure to deploy capital quickly, especially in Africa where governments promise easy access to land. Due diligence on community impacts often gets rushed or ignored entirely. We see the social safeguards as obstacles to overcome rather than essential protections.”

The Speculation Economy

Land has increasingly become a financial asset, with investment funds treating African farmland as a commodity to be bought, held, and sold for profit. This financialization drives up land prices and incentivizes the acquisition of large tracts, typically at the expense of indigenous communities.

The Land Matrix Initiative reports that since 2000, nearly 1,000 large-scale land deals for agriculture have been recorded across Africa, with Mozambique experiencing 110 deals, followed by Ethiopia and Cameroon. Many of these deals involve speculative investment rather than productive use, leaving land idle while communities that depend on it for survival are displaced.

Legal Frameworks and Their Failures

African legal systems generally fail to protect indigenous communities from corporate land acquisitions, often actively facilitating displacement through colonial-era land laws that vest ownership in the state rather than recognizing customary tenure systems.

The Colonial Legacy

Most African countries inherited colonial legal systems that treated indigenous land tenure as legally invalid, vesting all “unoccupied” land in the state. These laws ignore the reality that indigenous communities have sophisticated land management systems based on customary law rather than formal title deeds.

Professor Liz Alden Wily, a land tenure specialist who has worked across Africa, explains the systematic bias: “Colonial governments deliberately constructed legal systems that would enable land acquisition by settler farmers and companies. Post-independence governments have largely maintained these systems because they benefit ruling elites who profit from land deals”.

International Law vs. National Practice

International law provides strong protections for indigenous land rights, particularly the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which requires free, prior, and informed consent for any project affecting indigenous territories. However, most African governments fail to implement these protections, instead actively facilitating corporate land acquisitions.

The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights has established the Working Group on Indigenous Populations/Communities, but its recommendations carry limited enforcement power. National courts occasionally rule in favor of indigenous communities, but enforcement remains weak and corporate interests often prevail through political pressure.

Environmental Consequences of Displacement

Corporate land acquisitions often cause severe environmental degradation, undermining the conservation justifications commonly used to legitimize indigenous displacement.

Large-scale monoculture plantations destroy biodiversity, deplete soil nutrients, and contaminate water sources. The Land Matrix Initiative reports that intensive agricultural projects “seriously impact” local ecosystems, often causing more environmental damage than the traditional land use practices they replace.

The displacement of indigenous communities also removes the primary guardians of African ecosystems. Research consistently shows that indigenous territories have lower deforestation rates and higher biodiversity than government-protected areas or private concessions.

Gender Dimensions of Displacement

Women bear disproportionate costs from corporate land acquisitions, as displacement often destroys social support networks and economic opportunities while increasing vulnerability to violence and exploitation.

Research in East Africa reveals that “women face many barriers to land inheritance as result of customary laws and socio-cultural norms” and are often “excluded from land related consultations and resettlement”. When displacement occurs, women lose not only land access but also their traditional roles in community decision-making.

The Maasai women’s experience in Tanzania provides a stark illustration. Human Rights Watch reports that forced evictions have pushed many women into prostitution as traditional livelihood systems collapsed. The destruction of community structures leaves women particularly vulnerable to exploitation and abuse.

Child Labor and Educational Disruption

Corporate land acquisitions frequently lead to increased child labor and educational disruption as displaced families struggle to rebuild their livelihoods. Children often work in the same plantations that displaced their communities, trapped in cycles of exploitation.

Research in Uganda’s oil palm sector documents widespread use of child labor on plantations established on land acquired from local communities. The displaced families, lacking alternative income sources, send children to work on the plantations for survival wages.

Educational disruption compounds these problems. When communities are displaced, children lose access to schools and must contribute to household income rather than attending classes. This perpetuates cycles of poverty and marginalization across generations.

Health Impacts of Displacement

Forced displacement from ancestral territories causes severe physical and mental health impacts that extend far beyond immediate relocation trauma. The destruction of traditional food systems, loss of medicinal plants, and contamination of water sources create lasting health crises.

Research in the Democratic Republic of Congo’s palm oil plantations documents systematic exposure of workers and nearby communities to toxic pesticides without adequate protection. Many of these workers are members of communities displaced by the same plantations, forced to accept dangerous employment for survival.

The loss of traditional territories also destroys indigenous knowledge systems about medicinal plants and healing practices. Elderly community members report increased depression and anxiety following displacement, while traditional healers lose access to the plant medicines that form the basis of indigenous healthcare systems.

Resistance and Resilience

Despite facing overwhelming odds, indigenous communities across Africa have developed sophisticated resistance strategies to corporate land grabs, from legal challenges to international advocacy campaigns.

Legal Strategies

The Ogiek people’s successful case before the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights demonstrates the potential for legal resistance. In 2017, the Court ruled that Kenya had violated Ogiek rights by forcibly evicting them from the Mau Forest, ordering the government to pay reparations and ensure meaningful consultation on future projects.

Similar legal victories have occurred across the continent. In 2024, civil society organizations successfully challenged a World Bank project that would have displaced 84,000 people in southern Tanzania by expanding Ruaha National Park. The World Bank halted funding following sustained advocacy pressure.

International Advocacy

Indigenous communities increasingly use international advocacy to pressure corporations and governments. The Maasai have successfully mobilized international attention to their plight, leading to condemnation from human rights organizations and pressure on the Tanzanian government.

Digital technologies enable communities to document violations in real-time and share evidence with international advocates. GPS mapping and camera equipment allow precise documentation of land invasions and human rights violations, providing crucial evidence for legal challenges and advocacy campaigns.

Community Organizing

Grassroots organizing remains the foundation of resistance to corporate land grabs. Communities across Africa have formed coalitions to share information, coordinate responses, and support each other’s struggles.

The success in reversing the deregistration of 25 villages in Tanzania’s Ngorongoro Crater and Serengeti demonstrates the power of coordinated community action. When civil society organizations united Maasai communities in protest, the government was forced to reverse its decision.

International Complicity and Responsibility

Corporate land grabs in Africa cannot be understood without examining the international systems that enable and profit from indigenous displacement. European companies, development banks, and consumers all bear responsibility for the human rights violations that make their investments and products possible.

Supply Chain Responsibility

International companies sourcing agricultural products from Africa often benefit from land grabbing while claiming ignorance of displacement in their supply chains. European supermarkets sell palm oil, coffee, and other products grown on land seized from indigenous communities, yet maintain they cannot be held responsible for human rights violations by their suppliers.

The European Union’s proposed Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive aims to address these issues by requiring companies to conduct human rights due diligence throughout their supply chains. However, the directive faces strong industry opposition and may be weakened before implementation.

Development Finance Reform

European development banks have begun reforming their safeguards following criticism of their role in facilitating displacement. However, these reforms often focus on procedural improvements rather than addressing the fundamental problem of financing projects that displace indigenous communities.

A 2019 Human Rights Watch investigation of European development bank investments in DRC palm oil plantations concluded that “structural failures in the way the banks operate” enable human rights violations. The banks “do not assess the potential human rights impacts of the projects they invest in and all do little to disclose relevant information to communities that might be impacted.”

Economic Arguments and Their Failures

Governments and corporations typically justify land acquisitions by claiming they bring development, employment, and modernization to rural areas. However, evidence consistently shows that the economic benefits are minimal compared to the costs imposed on displaced communities.

Employment Promises vs. Reality

Corporate land acquisitions typically promise significant employment for local communities, but research shows these jobs are usually seasonal, low-paid, and inadequate to replace lost livelihoods from traditional land use.

A study of large-scale agricultural investments in Kenya, Madagascar, and Mozambique found that “many LSAIs jobs were seasonal and low-paid, making the household less able to cope with food shortages”. Workers employed by investment projects “adopted more coping strategies than contract farming households,” indicating greater food insecurity.

Infrastructure Development Claims

Corporations often promise infrastructure development as justification for land acquisitions, claiming that roads, schools, and health facilities will benefit local communities. However, research shows that promised infrastructure frequently fails to materialize or serves corporate rather than community needs.

Dr. Albert Makochekanwa’s analysis of foreign land deals across Africa found that “very few affected people were meaningfully compensated” and that promised benefits often failed to materialize. The study recommended that “all potential benefits promised by the investors should be signed and have fixed periods upon which they are expected to accrue to the affected communities.”

Food Security Paradox

One of the most tragic aspects of corporate land grabs is that they often undermine food security in the name of enhancing it. Companies claim that large-scale agricultural investments will increase food production, yet the evidence shows they typically worsen food insecurity for affected communities.

Export Agriculture vs. Local Food Systems

Most corporate land acquisitions focus on export crops or biofuels rather than food for local consumption. This orientation means that even successful projects may increase total agricultural production while worsening local food security.

Research in sub-Saharan Africa shows that “agricultural investment ventures of multinational companies continue to undermine the livelihood of indigenous communities”. The displacement from fertile agricultural land forces communities to relocate to marginal areas where food production is more difficult and less reliable.

Traditional Food Systems Destruction

Indigenous communities typically maintain sophisticated food systems that combine crop agriculture, livestock, hunting, gathering, and fishing. Corporate land acquisitions destroy these integrated systems, replacing them with monoculture plantations that provide few nutritional benefits to local populations.

The loss of traditional food systems has particularly severe impacts on women, who typically bear primary responsibility for household nutrition. When traditional gathering areas are converted to plantations, women lose access to wild vegetables, fruits, and medicinal plants that form essential components of community diets.

Climate Change and Displacement Intersection

Climate change compounds the challenges facing indigenous communities by increasing pressure for land acquisitions marketed as climate solutions while simultaneously making traditional territories less viable for subsistence.

False Climate Solutions

Carbon offset schemes and renewable energy projects increasingly drive land acquisitions that displace indigenous communities. These “green grabs” use climate rhetoric to justify land seizures, claiming that indigenous land use contributes to emissions while corporate projects will mitigate climate change.

However, research shows that indigenous territories typically have lower carbon emissions than corporate plantations or conservation areas. The displacement of communities that have sustainably managed ecosystems for centuries often increases rather than reduces emissions.

Climate Adaptation Needs

Indigenous communities need support for climate adaptation strategies that build on traditional knowledge rather than displacing them from ancestral territories. Traditional farming and livestock systems often demonstrate remarkable resilience to climate variability when not disrupted by corporate land acquisitions.

The Maasai pastoral system, for example, has evolved over centuries to cope with drought and environmental variability through mobility and diversified livestock management. Confining pastoralists to small areas or displacing them entirely destroys these adaptive strategies, making communities more vulnerable to climate impacts.

Regional Variations and Patterns

While corporate land grabs affect indigenous communities throughout Africa, specific patterns vary by region, reflecting different legal systems, political economies, and types of investments.

East Africa: Conservation and Tourism

East African countries, particularly Tanzania and Kenya, frequently use conservation and tourism justifications for indigenous displacement. The region’s reputation for wildlife and scenic landscapes makes it attractive to tourism investors who profit from excluding local communities from traditional territories.

The Maasai experience across both Kenya and Tanzania demonstrates how conservation rhetoric masks commercial interests. Tourism companies benefit from exclusive access to wildlife areas, while communities that traditionally coexisted with wildlife are portrayed as threats to conservation.

West Africa: Agricultural Expansion

West African land grabs typically focus on agricultural expansion, particularly palm oil and other cash crops. Countries like Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Ghana have experienced significant agricultural investments that displace forest communities and smallholder farmers.

The region’s history of civil conflict has weakened traditional authority structures and land tenure systems, making communities more vulnerable to displacement. Corporate investors often exploit post-conflict situations to acquire land cheaply from governments eager for foreign investment.

Central Africa: Extractive Industries and Logging

Central African countries experience land grabs driven primarily by extractive industries and commercial logging. The Democratic Republic of Congo exemplifies these patterns, with palm oil plantations, mining operations, and logging concessions displacing indigenous communities throughout the country.

Research shows that logging companies have “acquired” roughly 1 million hectares of indigenous territory in the DRC since 2000. These acquisitions typically involve foreign companies exploiting weak governance systems and conflict situations to gain access to valuable forest resources.

The Role of Technology in Land Grabs

Modern technology enables both more efficient land grabbing and more effective resistance by indigenous communities. Satellite imagery, GPS mapping, and digital communications have transformed how land acquisitions occur and how communities respond.

Corporate Surveillance and Mapping

Corporations use satellite imagery and aerial surveillance to identify valuable land and plan acquisitions. This technology allows investors to assess agricultural potential, forest resources, and mineral deposits without consulting local communities or even visiting areas in person.

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) enable precise mapping of concession boundaries and resource extraction plans. However, these technical assessments typically ignore customary land boundaries and traditional resource management systems, treating inhabited territories as empty land available for acquisition.

Community Documentation and Resistance

Indigenous communities increasingly use the same technologies to document their land rights and resist corporate acquisitions. GPS devices allow precise mapping of customary territories, while cameras enable real-time documentation of violations.

Digital communications platforms help communities share information, coordinate responses, and connect with international advocates. Social media campaigns have proven particularly effective at generating international pressure on governments and corporations engaged in land grabbing.

Psychological and Cultural Trauma

The displacement of indigenous communities from ancestral territories causes profound psychological and cultural trauma that extends far beyond immediate material losses. The destruction of sacred sites, disruption of cultural practices, and severing of spiritual connections to land create lasting harm that affects entire communities across generations.

Spiritual Connections to Land

For most indigenous African communities, land represents far more than an economic resource. Traditional territories contain sacred sites, ancestral burial grounds, and locations essential to religious and cultural practices. Corporate land acquisitions typically show no respect for these spiritual dimensions, treating sacred sites as obstacles to development.

The Anuak people’s connection to the Gambella region exemplifies these deep spiritual relationships. Traditional Anuak cosmology centers on specific landscapes and ecosystems that have been disrupted by large-scale agricultural projects. Elder Ochalla Nyikaw explains: “For us, the land is not just dirt to be sold. It contains our ancestors, our spirits, our whole way of understanding the world”.

Intergenerational Knowledge Transmission

Indigenous communities maintain sophisticated knowledge systems about ecology, agriculture, medicine, and resource management that depend on continued access to traditional territories. Displacement disrupts the transmission of this knowledge between generations, causing irreversible cultural losses.

Young people separated from ancestral lands cannot learn traditional ecological knowledge through direct experience. This disruption of knowledge transmission threatens the long-term survival of indigenous cultures, even when communities eventually gain access to new land.

International Legal Mechanisms and Their Limitations

While international law provides strong protections for indigenous land rights, enforcement mechanisms remain weak and often fail to prevent displacement or provide effective remedies when violations occur.

The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, adopted in 2007, establishes the principle of free, prior, and informed consent for any project affecting indigenous territories. However, most African governments have not implemented domestic legislation to enforce these protections.

Article 32 of the Declaration requires states to “consult and cooperate in good faith with the indigenous peoples concerned through their own representative institutions in order to obtain their free and informed consent prior to the approval of any project affecting their lands”. In practice, consultations are typically superficial or nonexistent.

African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights

The African Court has issued important rulings protecting indigenous land rights, particularly in the Ogiek case against Kenya. However, the Court’s jurisdiction is limited and many African governments do not accept its authority or implement its decisions.

The Ogiek victory demonstrates both the potential and limitations of regional human rights mechanisms. While the Court ordered Kenya to protect Ogiek rights and pay reparations, the government has continued evicting community members, showing that legal victories do not automatically translate to practical protection.

Investor-State Dispute Settlement

International investment agreements typically provide stronger protections for corporate investors than for indigenous communities. Investor-state dispute settlement mechanisms allow corporations to sue governments for policies that might reduce investment returns, including measures to protect indigenous rights.

These asymmetrical protections mean that governments face financial penalties for protecting indigenous communities but rarely face consequences for facilitating their displacement. The threat of investor lawsuits creates perverse incentives that prioritize corporate profits over human rights.

Corporate Social Responsibility and Its Failures

Many corporations involved in land acquisitions have adopted corporate social responsibility (CSR) policies that claim to respect indigenous rights and contribute to sustainable development. However, these voluntary commitments typically fail to prevent displacement or provide meaningful remedies when violations occur.

Voluntary Standards vs. Binding Obligations

Most corporate commitments to respect indigenous rights rely on voluntary standards rather than binding legal obligations. Companies can adopt impressive-sounding policies while continuing to profit from land acquisitions that displace communities.

The Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) exemplifies these limitations. Despite requiring “free, prior, and informed consent” from affected communities, RSPO certification has not prevented palm oil companies from displacing indigenous communities across Africa and Southeast Asia.

Greenwashing and Public Relations

Corporate social responsibility often functions more as public relations strategy than genuine commitment to human rights. Companies invest heavily in marketing their environmental and social credentials while continuing practices that harm indigenous communities.

The emergence of “green grabbing” demonstrates how environmental rhetoric can legitimize displacement. Companies frame carbon offset projects and conservation schemes as beneficial to indigenous communities while excluding them from traditional territories and decision-making processes.

The Economics of Resistance

Indigenous resistance to corporate land grabs imposes economic costs on corporations and governments, demonstrating that displacement is not always the most profitable strategy for land acquisition.

Cost of Conflict

Sustained community resistance increases the costs of land acquisition projects through delays, legal challenges, and reputational damage. Companies may spend more on security, legal fees, and public relations than they would on meaningful community consultation and benefit-sharing agreements.

The Maasai resistance to tourism projects in Tanzania has generated significant international attention and pressure on both the government and tourism companies. This attention imposes reputational costs that may exceed the economic benefits of forced displacement.

Alternative Development Models

Some successful agricultural projects have demonstrated that respecting indigenous land rights can be more profitable than displacement-based models. Contract farming arrangements that maintain community land ownership while providing technical support and market access have shown positive results in several African countries.

Research in Kenya, Madagascar, and Mozambique found that “households with members engaged in contract agreements with LSAIs adopted fewer coping strategies and were less food insecure than other households” compared to those affected by land acquisition projects.

Future Scenarios and Projections

Current trends suggest that corporate land grabs will intensify in coming years as climate change, population growth, and resource scarcity increase pressure on African land. However, growing awareness and resistance may also create opportunities for more equitable development models.

Climate-Driven Land Pressure

Climate change will likely increase corporate interest in African land as other regions become less suitable for agriculture. Rising temperatures and changing precipitation patterns may make African territories more valuable relative to traditional agricultural areas in temperate regions.

The expansion of carbon offset markets will create new incentives for land acquisition, particularly for forestry and renewable energy projects. Without stronger protections for indigenous rights, these “green” investments may displace more communities than traditional agricultural projects.

Technological Disruption

Advances in precision agriculture, biotechnology, and renewable energy may reduce the land area needed for corporate projects, potentially decreasing displacement pressures. However, these technologies may also make previously marginal lands more attractive for investment, extending corporate reach into previously untouched indigenous territories.

Blockchain technology and satellite monitoring could provide new tools for documenting and protecting indigenous land rights, but the same technologies could also facilitate more efficient land grabbing by improving investor due diligence and resource assessment capabilities.

Recommendations for Reform

Addressing corporate land grabs requires comprehensive reforms across multiple levels, from local land tenure systems to international investment agreements. The scale and urgency of indigenous displacement demand immediate action by governments, corporations, and international organizations.

Legal and Policy Reforms

African governments must recognize and protect indigenous land tenure systems through constitutional amendments and comprehensive land legislation. This requires moving beyond colonial-era laws that treat customary tenure as legally invalid.

Key legal reforms should include:

- Constitutional recognition of indigenous land rights

- Mandatory free, prior, and informed consent for all land acquisitions affecting indigenous territories

- Establishment of indigenous land registries and mapping programs

- Creation of specialized courts with expertise in indigenous law and customary tenure systems

- Implementation of benefit-sharing agreements that ensure communities receive fair compensation for land use

International Investment Reform

International investment agreements must be reformed to prioritize human rights over investor profits. Current investor-state dispute settlement mechanisms create perverse incentives that encourage land grabbing while penalizing governments that protect indigenous rights.

Essential reforms include:

- Human rights impact assessments for all international investments

- Binding corporate liability for human rights violations in supply chains

- Removal of investor-state dispute settlement provisions that conflict with human rights obligations

- Mandatory community consultation and consent procedures for development finance institutions

- Creation of international complaint mechanisms accessible to affected communities

Corporate Accountability Measures

Corporations must be held legally accountable for the human rights impacts of their land acquisitions and supply chains. Voluntary corporate social responsibility initiatives have proven inadequate to prevent displacement and abuse.

Necessary accountability measures include:

- Legal liability for parent companies regarding subsidiary operations

- Mandatory human rights due diligence throughout supply chains

- Public disclosure of land acquisition agreements and community impact assessments

- Compensation funds for communities affected by corporate operations

- Exclusion of companies with human rights violations from public procurement and development finance

The Way Forward: Community-Led Solutions

The most sustainable solutions to corporate land grabs must center indigenous communities as decision-makers rather than passive beneficiaries of external development. Community-led approaches that build on traditional knowledge and governance systems offer the greatest potential for equitable development.

Indigenous Land Mapping and Documentation

Supporting indigenous communities to map and document their traditional territories provides essential tools for resisting land grabs and claiming legal recognition. GPS technology and geographic information systems enable precise documentation of customary boundaries and resource management systems.

However, mapping initiatives must be controlled by communities themselves rather than external organizations. Previous mapping projects have sometimes facilitated land grabbing by providing detailed information to potential investors while failing to secure legal protection for mapped territories.

Traditional Governance Strengthening

Indigenous communities maintain sophisticated governance systems for managing land and natural resources. Strengthening these traditional institutions provides alternatives to state-controlled development that has facilitated most land grabbing.

Support for traditional governance should include:

- Recognition of customary law in national legal systems

- Capacity building for traditional authorities to engage with external actors

- Documentation and preservation of customary legal knowledge

- Integration of traditional institutions with formal government structures

- Financial support for community-controlled development initiatives

Community-Controlled Development

The most successful development projects affecting indigenous communities have been those controlled by the communities themselves rather than imposed by external actors. Community-controlled initiatives can achieve development goals while respecting indigenous rights and maintaining cultural integrity.

Examples include community-managed forests that generate income through sustainable timber harvesting, ecotourism projects that showcase indigenous culture while maintaining community control, and agricultural cooperatives that improve productivity while preserving traditional farming systems.

Conclusion: Reclaiming Dignity and Rights

The systematic displacement of indigenous communities through corporate land grabs represents one of Africa’s most urgent human rights crises. Over 12.3 million hectares of ancestral territories have been seized since 2008, displacing an estimated 2.8 million people whose families have lived on these lands for centuries.

The evidence is overwhelming: corporate land acquisitions consistently fail to deliver promised benefits while imposing devastating costs on indigenous communities. Employment opportunities are minimal and low-paid, infrastructure development rarely materializes, and agricultural productivity gains come at the expense of food security for displaced populations.

Yet the crisis extends far beyond immediate material losses. The destruction of sacred sites, disruption of cultural practices, and severing of spiritual connections to land create psychological trauma that affects generations. Traditional knowledge systems about ecology, medicine, and sustainable resource management disappear when communities are separated from ancestral territories.

The international community bears significant responsibility for this crisis. European development banks finance projects that displace communities while claiming to promote sustainable development. International investment agreements protect corporate profits while providing no meaningful protection for indigenous rights. Consumers in wealthy countries benefit from products grown on seized land while remaining ignorant of the human costs of their consumption.

The time for incremental reforms and voluntary corporate commitments has passed. What is needed now is fundamental restructuring of power relations that prioritize indigenous rights over corporate profits.

This requires legal recognition of indigenous land tenure systems, binding corporate accountability for human rights violations, and community control over development affecting traditional territories. International investment agreements must be rewritten to prioritize human rights over investor returns, while development finance institutions must abandon projects that displace communities regardless of their claimed benefits.

Most importantly, solutions must center indigenous communities as decision-makers rather than passive recipients of external development. Traditional governance systems, customary law, and indigenous knowledge offer proven alternatives to the destructive development model that has driven land grabbing across the continent.

The choice facing Africa and the international community is clear: continue enabling a development model based on displacement and exploitation, or support community-controlled alternatives that respect indigenous rights while achieving genuine human development.

Indigenous communities have stewarded Africa’s most productive and biodiverse landscapes for millennia. Their displacement impoverishes not only the affected communities but the entire continent. The future of African development depends on recognizing that indigenous rights are not obstacles to progress but essential foundations for sustainable and equitable development.

The evidence is clear, the moral imperative is undeniable, and the solutions are available. What remains is the political will to prioritize human dignity over corporate profits and community rights over development rhetoric. The millions of displaced Africans whose lives have been shattered by land grabbing deserve nothing less than complete transformation of the systems that have robbed them of their ancestral heritage.

Citations and Source Documentation

All citations in this investigation correspond to verified sources gathered during extensive research across multiple continents and databases. Full documentation available upon email to support the accuracy and verifiability of all claims made.

About Our Investigative Services

Seeking to expose corruption, track illicit financial flows, or investigate complex criminal networks? Our specialized investigative journalism agency has proven expertise in following money trails, documenting human rights violations, and revealing the connections between organized crime and corporate malfeasance across Africa and beyond.

Partner With Us for Impactful Change

Ready to drive transparency and accountability in your sector?

Our investigative expertise and deep industry networks have exposed billion-dollar corruption schemes and influenced policy reform across Africa.

Whether you’re a government agency seeking independent analysis, a corporation requiring risk assessment and due diligence, or a development organization needing evidence-based research, our team delivers results that matter.

Join our exclusive network of premium subscribers for early access to groundbreaking investigations, or contribute your expertise through our paid contributor program that reaches decision-makers across the continent.

For organizations committed to transparency and reform, we also offer strategic partnership opportunities and targeted advertising placements that align with our mission.

Uncover unparalleled strategic insights by joining our paid contributor program, subscribing to one of our premium plans, advertising with us, or reaching out to discuss how our media relations and agency services can elevate your brand’s presence and impact in the marketplace.

Contact us today to explore how our investigative intelligence can advance your objectives and create lasting impact.