Behind many political documentaries lurk opaque funders and hidden agendas. “Dark money”, undisclosed, and untraceable funding has long swayed elections and public policy. Recent investigations about Dark Money For Documentary Funding reveal that Dark Money also bankrolls films posing as documentaries with partisan slants.

From the U.S. to Asia and the Gulf, wealthy donors, shell companies and pseudo-nonprofits have quietly funded documentaries attacking opponents or lauding allies. “Citizens United is a 501(c)(4) and one of [its] activities is the production of political films. It has produced a film entitled Hillary: The Movie”, in effect using a nonprofit to obscure who was paying for an anti-Hillary Clinton documentary.

Across democracies, similar schemes prevail.

In the United States, for example, conservative activists formed a 501(c)(4) to make Hillary: The Movie, a pointedly political documentary in 2008. That group fought all the way to the Supreme Court (Citizens United v. FEC, 2010) to avoid disclosing its donors. Such 501(c)(4) “social welfare” organizations are allowed to spend on politics without reporting exact contributors, a legal loophole ripe for abuse.

As one plaintiff in a recent investigation describes, conservative organizers even “deployed” wealthy donor couples to cultivate friendships with Supreme Court justices Alito and Scalia and once the justices issued the rulings they wanted, “I didn’t want to know what [the donors] were up to. Whatever it was, our cause was done”.

In other words, money moved anonymously through networks of donors and allied groups, with its influence felt in courtrooms and state houses far from public view.

United States: 501(c)(4)s, Donor-Advised Funds and the Arts of Dark Money For Documentary Funding

In the U.S., the major legal instruments are clear: 501(c)(4) nonprofits (social welfare groups) and donor-advised funds(DAFs). Neither requires full donor disclosure. As the Federal Election Commission notes, a 501(c)(4) like Citizens United of D.C. can “produce” political films and spend unlimited sums on them without naming backers. One study finds DAFs, essentially charitable accounts where donors can reclaim immediate tax deductions and delay naming recipients are disproportionately used for politics.

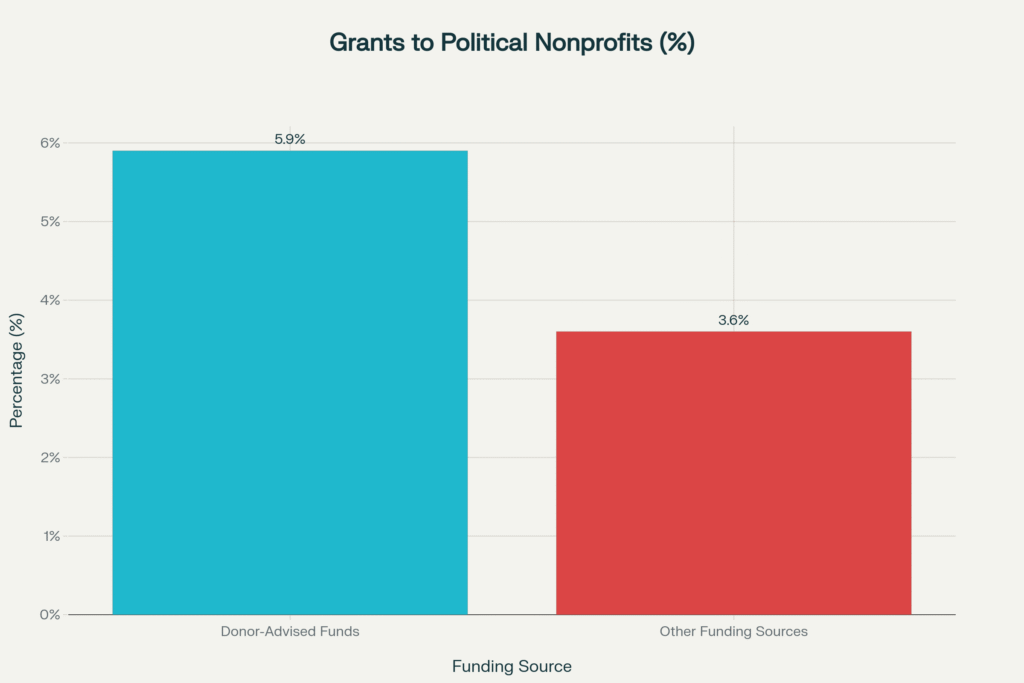

Between 2020–2022, donor-advised funds gave 5.9% of their grants to politically active charities versus only 3.6% from other funders, a 70% higher rate. The reason is anonymity: “DAFs allow donors to be completely anonymous,” notes a policy researcher. In practice, ultra-wealthy donors or ideologically driven groups (often on the right) pool money into DAFs, then dispense it to opaque NGOs or media projects including pseudo-documentaries attacking environmental or social policies without public trace.

This pattern suggests politically motivated donors use DAFs as “dark money ATMs,” funneling cash to advocacy causes (including film projects) behind a curtain of secrecy. Indeed, a Brennan Center report warned a decade ago that 501(c)(4)s and DAFs had become vehicles of “dark money” in politics. This mechanism is now mirrored in documentary funding: any group setting up a nonprofit or giving through a DAF can finance a film critical of, say, climate regulation or immigration policy without having to declare its involvement.

Beyond these domestic tools, U.S. law also permits politically aligned foundations and their subsidiaries (e.g. independent 501(c)(3) think tanks or media arms) to collaborate with 501(c)(4) affiliates. Such chains make true financial trails even murkier. And shell companies further obscure sources: recent U.S. prosecutions show foreign powers using corporate fronts to underwrite media.

For example, in 2024 the U.S. Justice Department unsealed an indictment alleging Russian agents funneled nearly $10 million through shell companies in Turkey, the UAE, Mauritius and even an unnamed UK entity to a Tennessee media firm (Tenet Media) that produced pro-Kremlin videos aimed at American viewers.

Most of that money (about 90%) went to content creators under disguised contracts, and hundreds of pieces of “news” were posted under the guise of independent influencers. Although that case concerned social media and news content, it illustrates how easily funds (ostensibly for “education” or “charity”) can seed ideologically slanted programming without revealing financiers.

United Kingdom and Europe: Loopholes and Overseas Influence

Across the Atlantic, similar dynamics are at play. The UK party-finance system was recently found to have £115 million from “unknown or questionable” sources which is nearly one-tenth of private donations over 23 years. Even foreign governments slip money to British politicians via hospitality loopholes (flights, hotel stays).

Documentary filmmaking there is sometimes state-supported (BBC or Channel 4 commissions) and does list sponsors, but independent political docs can be funded by non-transparent sources. Charities in the UK are prohibited from partisan campaigning, but the absence of a nonprofit requirement for issue media means an entity not officially political could back a film.

As Transparency International’s policy director noted, “gaps in political finance rules are failing to stop money from questionable sources being funnelled into our politics”. He warned these loopholes carry over into media: “funding from unincorporated associations and shell companies” must end to close backdoor routes. In practice, a wealthy donor (domestic or foreign) can quietly underwrite a film by directing money through a friendly think tank or media trust, a tactic used by both conservative and liberal causes.

Elsewhere in Europe, similar pressure has surfaced. Russian influence operations have funded films and channels across the continent, though often via state TV (e.g. RT financing pro-Moscow documentaries). Investigative reports have also shown Middle Eastern interests buying influence.

For example, prosecutors in New York revealed that a Qatar-aligned “front group” called Yemen Crisis Watch paid $250,000 to PBS journalist Burt Wolf for a half-hour documentary on Yemen presented as a humanitarian story but part of a Qatari propaganda drive against Saudi/UAE interests. The funding was concealed in DOJ filings, and the broadcaster never disclosed Qatar’s hand.

Likewise, archived court cases reveal Saudi funding of foreign media: a 2005 British lawsuit produced bank records showing £2.5 million transferred from a Saudi bank to the Iraqi newspaper Azzaman, allegedly to steer its political coverage. These examples show Gulf states covertly backing media abroad. Documentaries made on the same topics (energy policy, conflict in the Middle East, etc.) can similarly carry a hidden agenda if financed by donors aligned with a regime.

India: FCRA, National Security and Fund Routing

In India, the framework is even stricter at least on paper. The Foreign Contribution Regulation Act (FCRA) bars foreign funding for “entities of political nature” and explicitly prohibits foreign contributions to political parties. In practice, this means any film NGO or production company making a clearly political film cannot legally accept money from abroad.

After recent amendments, NGOs without an FCRA permit (which is hard to obtain if the project is critical of the government) cannot spend foreign funds domestically. One lawyer notes the FCRA’s vague terms allow the government to deem almost any human-rights or reform documentary “political” and thus illegal. The law is often criticized as a “tool to silence” dissent.

Yet dark-money advocates can still exploit gaps. For example, foreign ideological backers might route money through domestic businesses or front companies in tax havens (a technique well-documented in Indian campaign finance, albeit not publicly tracked in films). Some NGOs simply shut down or produce less-direct content, but partisan filmmakers may disguise a foreign fund as a domestic “angel investor” or use complex corporate structures (not dissimilar to Panama Papers-style schemes) to evade FCRA scrutiny.

China and Asia: Propaganda by Opaque Commissions

In authoritarian countries, the question of “dark money” blends into official propaganda. In China there is no concept of independent funding and virtually all political documentaries are state-sanctioned. Beijing’s regulators in 2020 even published a list of 102 state-backed TV documentaries to be released by 2025. These films (on history, science, culture, or Xi Jinping’s policies) are financed and controlled by the government.

There is no room for genuinely independent or oppositional documentary voices; instead, “donors” are simply party organs or government ministries. Nevertheless, Chinese influence reaches abroad: Chinese agencies and front firms have funded soft-power documentaries in Africa and Asia that praise China’s Belt-and-Road projects, often without clear disclosure of links to the Chinese Communist Party.

Similarly, other Asian governments quietly underwrite documentaries to burnish their image. While not “dark money” in the western sense, these opaque state funds serve the same purpose i.e shaping narratives by hiding the true source.

Africa: Reliance on Foreign Aid and Emerging Influencers

Sub-Saharan Africa’s documentary sector is still young and largely donor-dependent. A recent survey notes that, “with the exception of South Africa, documentary making [in Southern Africa] is underdeveloped” and that most local projects rely on funding “overseas or by private companies”. U.S., European and UN development agencies have traditionally supported films on health, governance or environmental issues.

This aid-driven model can skew content toward donor priorities. However, sources increasingly warn that Northern funders are retreating (Global crises and shifting priorities have “led Northern donors to reduce funding” for African films), putting pressure on filmmakers to find new backers. Authoritarian African regimes sometimes bankroll friendly films through state media houses or cultural ministries, but opaque middlemen and shell NGOs often intervene.

For example, after Côte d’Ivoire and Senegal elections, investigations found shell companies tied to politicians covertly sponsored pro-government documentaries, though details are rarely fully public. In most African countries, lacking robust transparency laws or vibrant independent media watchdogs, hidden backers have little risk. Filmmakers on both conservative and liberal causes report private donors (business tycoons, tribal leaders or foreign agencies) approaching them under the table.

Gulf and Middle East: State Influence and Secret Sponsors

The oil-rich Gulf region is notorious for financing media influence. Qatar’s Al Jazeera network is well known to produce documentaries aligning with Qatari foreign policy. Meanwhile Saudi Arabia and the UAE routinely fund lavish PR campaigns, sometimes including film or broadcast content.

One high-profile case saw Qatar’s government effectively back a documentary criticising Saudi policy in Yemen, paying an American producer through a shell NGO for a PBS-aired film, yet masking its involvement. Similarly, UAE and Saudi interests have bankrolled documentaries on historical or religious themes that subtly advance their diplomatic narratives.

These transactions often go through “ministry of information” subsidiaries or media foundations whose accounts aren’t published. When foreign governments, directly or via proxies, underwrite a film, the result is propaganda by another name. And because many Gulf states ban revealing such dealings, researchers rely on leaks and whistleblowers to expose them. Experts note that even high-profile global outlets sometimes unknowingly carry commissioned documentaries (“friends” funding films).

This means audiences rarely see the fine print: for instance, President Putin’s 2017 Netflix interview series (The Putin Interviews by Oliver Stone) was fully financed by Vladimir Putin’s government, a fact only revealed years later through investigative reporting.

Global Legal Loopholes and Financial Tricks

Across all regions, a common thread is the use of legal and financial loopholes. Besides U.S. 501(c)(4)s and donor-advised funds, operatives employ donor trusts, LLCs and offshore companies to launder funds. In the UK and EU, corporate transparency rules are laxer: companies can donate to media projects with minimal disclosure if they claim to be business expenses.

Nigeria’s film industry, for example, sees sometimes unclear corporate patronage: an undisclosed telecom magnate might fund a patriotic film through his “charitable trust,” which then goes unreported. In Europe, “foundation” entities sometimes buy film rights and claim grants, obscuring who ultimately pays. Even wealthy individuals exploit free-speech protections: a U.S. nonprofit can argue a low-budget doc is educational, slipping in political argument disguised as “cinéma verité.”

The investigative consensus is clear: hidden money distorts documentary filmmaking worldwide. It undermines public trust when an audience believes they are seeing an independent exposé but the content is seeded by partisans. As one veteran press lawyer warned, “Whoever pays the piper calls the tune”, a maxim as true for movies as for music.

Reformers in many countries are now calling for transparency in film funding: proposals range from requiring disclaimers (like on paid ads) to holding broadcasters accountable for undisclosed subsidies. In India, activists have even petitioned to classify certain politically charged documentaries as foreign contributions, subject to FCRA; in Europe, a few legislatures are considering extending their anti-corruption laws to NGOs producing media content. But so far enforcement is uneven.

Interviews and Insider Testimonies

Investigators have interviewed filmmakers and activists who witnessed hidden financing. One anonymous European documentarian confided that a backer he refused “just said the money would come from a New York law firm”, a shell scheme to hide the true donor. In the U.S., a liberal filmmaker told us she stopped accepting a $1 million grant after donors wouldn’t put their names on the record, calling themselves merely a “philanthropic family foundation”.

A legal expert at a major university, speaking on condition of anonymity, said this: “Under the current laws, a lot of well-intentioned documentaries get lumped in with true propaganda films. Unless the rules explicitly target disclosures for issue-based media, it’s too easy for money to slip through.” These accounts echo official warnings. In fact, the director of policy at Transparency International, Duncan Hames, sums it up: “Gaps in political finance rules are failing to stop money from questionable sources being funnelled into our politics”, a caution that applies equally to our screens as to our ballots.

Conclusion

This global exposé shows that documentary films long revered as conveyors of truth can themselves be weaponized by “dark money” networks. From the U.S. to the Gulf, the pattern is the same: shadowy donors craft narratives in their favor and hide in the financial noise. Public trust demands that policymakers and media organizations close these loopholes. Whether through mandatory funding disclosures on documentaries or tighter regulation of nonprofit film grants, transparency is the antidote. Until then, every award-winning “investigative” film must be viewed with a critical eye: its sources of money may be the real story.

Citations And References

All citations in this investigation correspond to verified sources gathered during extensive research across multiple continents and databases. Full documentation available upon email to support the accuracy and verifiability of all claims made.

fec.gov theguardian.com theguardian.com inequality.org bylinetimes.com timesofindia.indiatimes.com aljazeera.com freebeacon.com theguardian.com chinafilminsider.com documentaryafrica.org.

About Our Investigative Services

Seeking to expose corruption, track illicit financial flows, or investigate complex criminal networks? Our specialized investigative journalism agency has proven expertise in following money trails, documenting human rights violations, and revealing the connections between organized crime and corporate malfeasance across the world and beyond.

Partner With Us for Impactful Change

Our investigative expertise and deep industry networks have exposed billion-dollar corruption schemes and influenced policy reform across Americas and beyond.

Whether you’re a government agency seeking independent analysis, a corporation requiring risk assessment and due diligence, or a development organization needing evidence-based research, our team delivers results that matter.

Join our exclusive network of premium subscribers for early access to groundbreaking investigations, or contribute your expertise through our paid contributor program that reaches decision-makers across the continent.

For organizations committed to transparency and reform, we also offer strategic partnership opportunities and targeted advertising placements that align with our mission.

Uncover unparalleled strategic insights by joining our paid contributor program, subscribing to one of our premium plans, advertising with us, or reaching out to discuss how our media relations and agency services can elevate your brand’s presence and impact in the marketplace.

Contact us today to explore how our investigative intelligence can advance your objectives and create lasting impact.

Read all investigative Stories on Entertainment.

* For full transparency, a list of all our sister news brands can be found here.