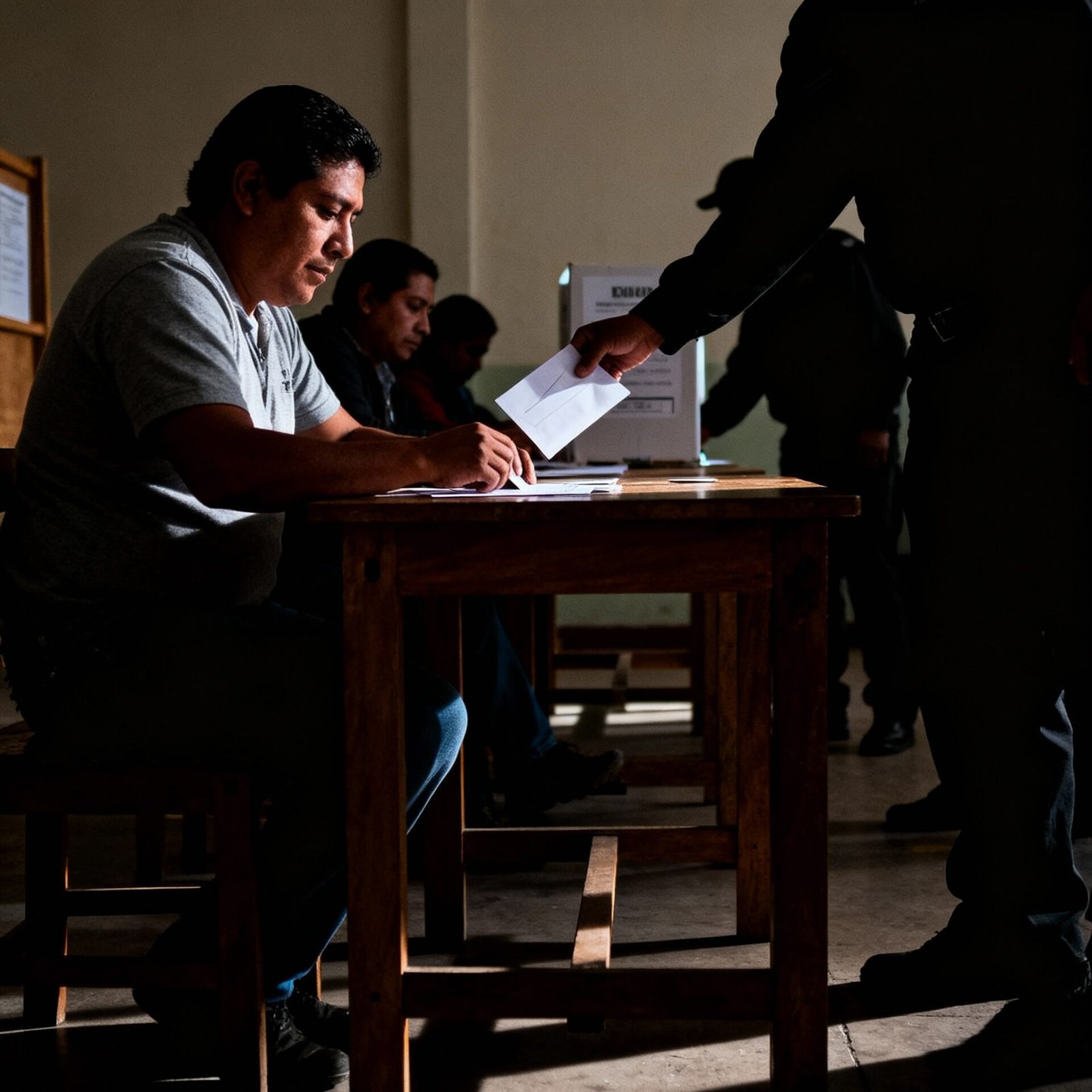

The 2024 local election campaign in Mexico was mired in violence. In late April 2024, two political candidates were murdered within hours of each other during campaign events reminding local voters and the world about drug cartel influence in Mexican Elections.

Noé Ramos Ferretiz, a mayoral hopeful in Edomex, was stabbed to death onstage at a rally. Hours later, Alberto Antonio García, a state-legislature candidate from the ruling party in Oaxaca, was found shot dead after two days in captivity.

These killings made headlines worldwide and underscored a grim reality: at least 30 candidates have been murdered during the current election cycle, already surpassing the toll of previous elections. Experts warn that this campaign is shaping up to be “the most violent one in recent years”, driven largely by drug cartel interference.

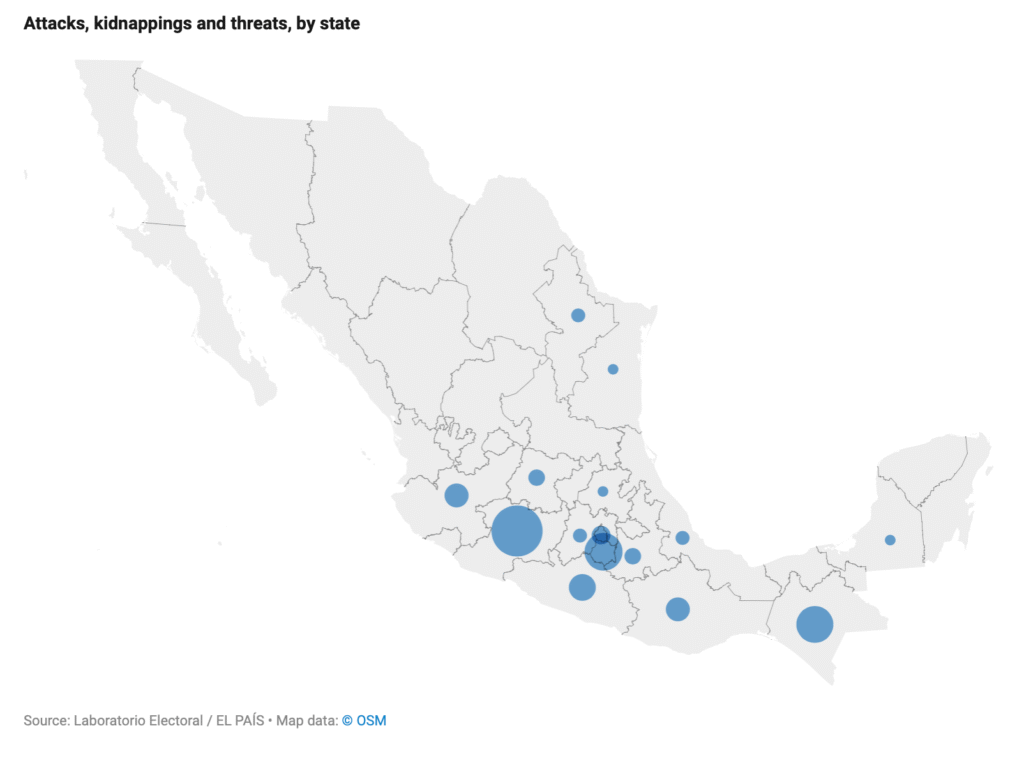

Cartels are not only killing candidates; they are shaping who runs, who wins, and who governs. Analysts from Mexico’s Laboratorio Electoral reported over 170 attacks on political figures so far including 29 assaults, 11 kidnappings and 77 threats. They find that criminal groups have effectively “authorized who can compete and govern, in an effort to pull the strings of local authorities”.

In other words, cartels vet and pressure political parties to select candidates who are acceptable to them. Daniela Arias of Laboratorio Electoral explains that organized crime “seeks to exercise political control in the territories they dominate”, using violence and intimidation as levers. As a result, elections in many regions resemble cartel-led appointments more than free contests.

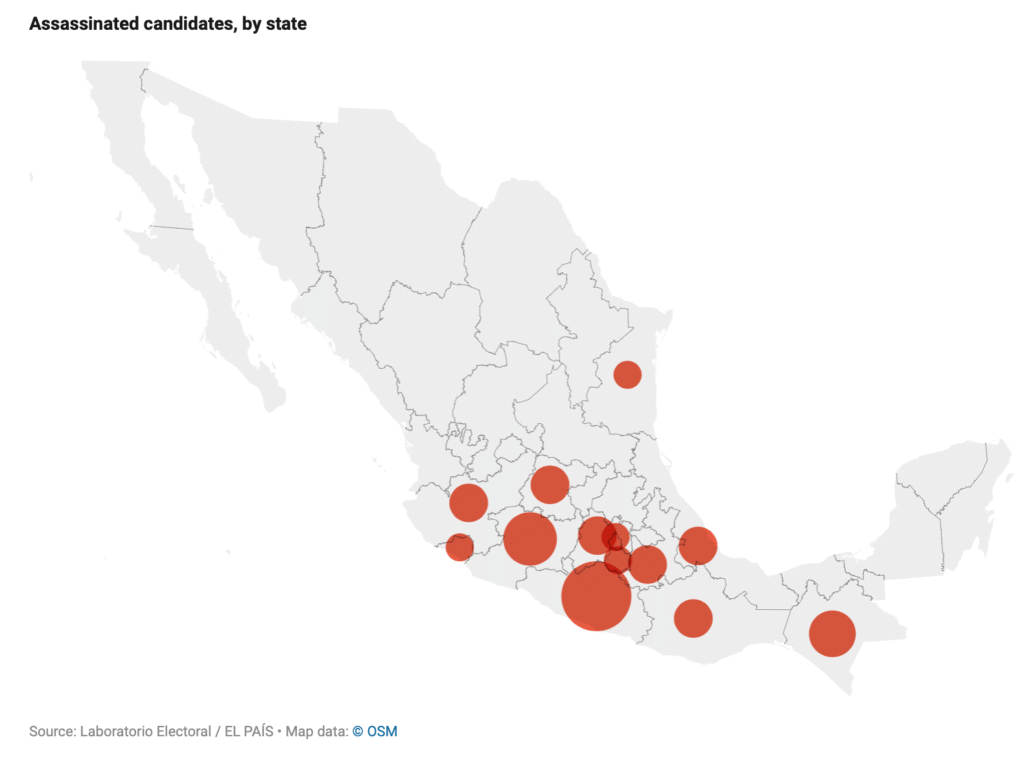

Data from think tanks and NGOs reveal how widespread the violence is. A recent EL PAÍS analysis shows that lethal attacks on candidates have occurred in 13 of Mexico’s 32 states, especially in the south and west. “The red flags are in Michoacán, Guerrero and Chiapas,” says Arturo Espinosa Silis of Laboratorio Electoral. In Guerrero alone, seven candidates have been killed; Michoacán saw four; Chiapas three; and other states including Oaxaca, Guanajuato and Puebla have recorded multiple victims.

The accompanying map illustrates the concentration of assassinated candidates: large red circles cluster in those key states. This pattern matches areas long plagued by cartel turf wars. In Chiapas, for example, local reports confirm a fierce contest between the Sinaloa Cartel and the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG). Gunmen often target anyone seen as standing between the gangs and control of the region.

Map of assassinated candidates by state (red circles) shows extreme violence in Guerrero, Michoacán and Chiapas, among other regions

Beyond killings, cartels deploy threats, kidnappings and other intimidation against candidates and their families. The same EL PAÍS report notes 34 candidates in Michoacán alone dropped out after being menaced by armed gangs. In scores of cases, election hopefuls are told bluntly “you don’t have permission” to run, as Antonio Plaza of the local Michoacán Primero party recounts.

In Ciudad Hidalgo, Michoacán, armed men have even summoned prospective councilors for “orientation” before allowing them to campaign. Another local official says extortion of municipal candidates is routine: if a candidate refuses a cartel’s backing or demands, he can expect bullets. As a result, many races end up uncontested or won by the cartel’s chosen proxy. Analysts emphasize that in such regions “the line that divides the state from organized crime becomes increasingly blurred”.

Communities in these areas describe an atmosphere of terror. Residents of small towns report feeling “abandoned” by the state, where police and officials stay out of gang way. According to Espinosa Silis, there are “areas of the country where there’s a total absence of the state, where neither the security forces nor local governments can act”. In such places, an ordinary campaign event can be deadly. Voters often stay home on election day, not trusting local ballots will be secret or safe. A US-borne “I Voted” sticker symbolizes a normal democracy, but in Mexico’s violence-torn regions even this basic civic act carries risk.

Chart of attacks, kidnappings and threats (blue circles) highlights Michoacán, Chiapas and other states as hotbeds of cartel intimidation, with dozens of candidates forced out of races

The problem extends well beyond 2024. At the midterm elections of 2021, Mexico endured one of its bloodiest campaigns on record. As Reuters documented, Sonoran candidate Abel Murrieta’s assassination was the “83rd politician killed in Mexico since September” 2020. By comparison, that year’s total nearly tripled the 2015 midterms.

According to consultancy Etellekt, political assassinations in 2021 were up more than a third from 2015. Murders and threats in 2021 were concentrated in a similar swath of states: Veracruz, Puebla, Oaxaca, Guerrero, the State of Mexico and Michoacán saw the majority of violence. Even earlier, during the 2018 election, 152 politicians were killed in ten months, an average of one per week. Each cycle, cartels appear to ratchet up their interference.

How Cartels Shape Candidates

Experts describe multiple tactics by which cartels bend elections to their will. As the Wilson Center’s María Calderón explains, gangs use “less visible techniques such as corruption” to manipulate outcomes. They often strike deals with parties: promising to steer votes or deliver campaign funds in exchange for policies or impunity. If a candidate breaks a cartel’s informal “pact” after winning office, he may face retaliation. In many towns, cartels effectively “invest” in candidates.

Wilson Center and Crisis Group analysts note that cartels demand that campaign contributions “bestow advantages or… demarcate lines of territorial control”. In practice, this means gangs bankroll loyalists and make sure challengers are too afraid to run. Those who refuse a cartel’s backing risk being branded troublemakers.

Installing or co-opting local officials has become a standard strategy. Researchers report that cartels often “install or co-opt candidates at the municipal level” to secure direct control over police and public resources. For example, towns in Michoacán have long seen cartel-linked mayors quietly consolidate power (sometimes while claiming to fight crime).

When municipal leaders align with a gang, that group gains access to intelligence on police actions, and can even use local police as cartel militias. Conversely, an anti-cartel candidate is likely to be at a deadly disadvantage. Calderón notes that when politicians “double-sell the plaza” by making deals with two rival cartels, instability and violence almost always follow.

Threats against voters and election workers are also widespread. Criminal gangs have been known to station armed lookouts at polling places or forcibly remove ballot boxes if results look unfavorable. In 2010, Amnesty International warned that the Philippines was facing a similar crisis: private militias backed candidates so ruthlessly that one election “was fought with bullets as well as ballots”.

In fact, the 2009 Maguindanao massacre in the Philippines, 63 people killed in a convoy of political supporters is often cited as a wake-up call about cartel-style intimidation. Mexico’s experience mirrors these dangers: local officials and observers say many votes in troubled areas today come at the barrel of a gun.

Analysts also point to more subtle electoral manipulation. In some “paradise municipalities” (as one report calls them), cartels exert almost complete sway behind the scenes. They may pressure parties not to register certain candidates, or to adopt muted campaigns that avoid the cartel’s turf. Some communities, like Cherán in Michoacán, have even thrown out the party system entirely to escape gang control, barring cartels from elections and banning political parties.

But such cases are rare exceptions. In most states, mainstream parties and even populist movements have found it difficult to respond. Mexico’s presidential administration has tended to downplay cartel influence on elections, stressing that “the state is omnipresent” even when carnage occurs. When President López Obrador finally acknowledged the death of Celaya mayoral candidate Gisela Gaytán (an AMLO ally killed in April 2024), he framed it as an attack on democracy. Yet at the same time he cautioned against politicizing security, leaving many victims feeling ignored.

Major Cartels and Municipal Hotspots

While the exact alliances vary, certain cartel groups and regions recur across reports. In the north, the Sinaloa Cartel (originally based in the state of Sinaloa) still wields power in border areas. Its factions, and those of its old ally La Familia (Michoacán), have battled Jalisco-based CJNG in states like Guanajuato, Michoacán and Guerrero. In central Mexico, CJNG’s rise under Nemesio “El Mencho” Oseguera has been a major shift: once a Jalisco local gang, it now claims territory from Colima and Jalisco to Guerrero and the State of Mexico. Chiapas has become a new battleground between Sinaloa and CJNG.

In east and northeast states, dissident Zetas factions (often called Gulf Cartel splinters) remain entrenched in Tamaulipas and Veracruz, contesting control of oil-rich regions. Each area sees different mafia “kingpins” in the wings during campaigns: for example, extortion rings based in Chihuahua City or Tijuana have been accused of backing certain Puebla candidates in exchange for immunity. Local press often identifies exactly which group is behind a given incident, but their names are too numerous to list here. What matters is that across Mexico, from Yucatán to Baja California, campaigns are being staged on cartel battlegrounds.

The victims of this violence are almost always municipal-level figures. Mayors, councilors and state legislators run the highest risk. According to ACLED, 80% of the violent incidents targeting political figures in 2024 involved local or regional office candidates. Cartels have little interest in the federal elections themselves; they focus on the towns where they already run illicit businesses. In practice, this means small or mid-size cities become the front lines.

ACLED data show that in states like Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo in Brazil, as well as Mexican states like Michoacán and Guerrero, local officials are being killed or threatened at unprecedented rates. In Brazil, a 2023 ACLED report noted 123 local officials were slain in five years, often by gangs and even rogue police militias.

The parallel is stark: Brazilian militias and Mexican cartels both see municipal governments as assets to capture or eliminate. In Mexico, cartels also engage in direct voter fraud: community members report that armed patrols sometimes escort groups of voters to choose cartel-approved candidates, or that ballots simply disappear during counting. All these forms of interference skew elections away from genuine representation.

Voices on the Ground

Interviews with those in affected communities bring the statistics to life. A former mayor from Tamaulipas, speaking anonymously to Crisis Group analysts, described elections under cartel rule as orchestrated shows: “We know who will win before anyone votes” if a cartel has already decided the outcome. Civic activists report that in some rural towns, election night is diverted to the local headquarters of the cartels. In Michoacán’s Tierra Caliente region, one village councilor told journalists that half the town’s men now carry guns instead of going to vote, as clashes between CJNG and rival groups spiral.

Municipal election judges (consejeros electorales) have faced extortion themselves: in 2023, Mexico’s electoral institute documented numerous cases of polling officials being paid off or threatened to change tallies. By contrast, national figures seem distant. Local leaders lament that state authorities rarely intervene until after violence happens. In interviews, federal prosecutors often echo a refrain: “Don’t get in between two dogs fighting,” implying they have limited resources to protect candidates.

Legal experts warn that such impunity is baked into the system. A former homicide investigator notes that even when attackers are caught, courts often fail to connect them to any higher-order conspiracy. Without witnesses willing to testify against cartel bosses, few masterminds face justice. This fosters a climate where citizens’ only recourse is self-defense or flight. The International Crisis Group warns that in some areas, citizens have already created vigilante groups or “community councils” to regain control of elections. But these ad hoc solutions often last only until the next election cycle.

Comparisons Abroad

Mexico’s crisis has echoes in other countries that allowed organized crime into politics. In Sicily’s 2022 local election, Reuters reported that former governor Salvatore “Toto” Cuffaro who was jailed for aiding the Mafia actively campaigned for a Palermo mayoral candidate. His involvement outraged anti-mafia prosecutors and citizens, who viewed it as a sign that Cosa Nostra still pulls strings in local elections.

In fact, political support for convicted gangsters has become a campaign strategy in parts of Italy: one anti-mafia judge lamented that letting rehabilitated mob figures freely influence politics is “like erasing history”. This mirrors Mexico, where even powerful leaders face criticism for seeming to tolerate narco-politicians.

Brazil provides another comparison: local gang militias have long vied for municipal influence. In Rio, the 2018 assassination of city councillor Marielle Franco highlighted how police-backed gangs were dictating politics. ACLED analysts note that between 2018 and 2022, Brazilian gang violence generated at least 273 violent events targeting public officials, with militias colluding with certain candidates. Like Mexico, Brazilian gangs use a mix of intimidation, cash and co-optation to sway city councils and mayorships.

Even Asia has seen parallels. During the Philippines’ 2010 elections, Amnesty International warned of “record levels” of political killings by private armies loyal to local power-brokers. The Maguindanao massacre (2009), where 63 people in a candidate’s convoy were slaughtered, had already shown how warlords impose candidates by force. Amnesty noted with alarm that many Filipino voters literally live under “private armies” for electoral purposes. Today, analysts of Mexico’s elections point to the same concept: in cartel-dominated towns, voting often occurs under armed escort, making ballots a façade.

A Crisis of Democracy.

The influence of organized crime on elections strikes at the heart of governance. When cartels decide who governs, public trust in democracy erodes. As Crisis Group observes, this fusion of crime and politics can even prompt citizens to reject formal elections altogether.

Early evidence suggests significant voter apathy: polling in violence-prone municipalities shows turnout falling by several percentage points compared to safer areas. Some activists warn of a feedback loop: violence discourages civic participation, which in turn makes it easier for cartels to dominate politics. If not checked, this cycle could expand beyond Mexico’s borders; scholars note that other Latin American regions with weak institutions, like parts of Central America, risk similar narco-politicization.

For U.S. readers and global policy analysts, Mexico’s crisis offers a cautionary tale. Despite massive attention to Mexico’s drug battles on highways, the quiet infiltration in the ballot box has received less notice. Yet it is precisely this hidden influence that may determine whether Mexico can secure its democracy. The 2024 elections will continue to unfold against this shadow.

Some proposals have emerged: from beefed-up federal protection for candidates, to international election observers, to declassifying intelligence on cartel funding. But local activists say only bold measures – like prosecuting illegal campaign contributions and dissolving compromised local governments – could begin to break the hold of the narcos.

Experts’ Outlook.

Analysts stress that no single solution exists. María Calderón of the Wilson Center argues for a “whole-of-society” approach: combining stronger policing with transparent political reforms. Laboratorio Electoral calls for better data-sharing among agencies, so that threats and attacks on candidates become a public crisis rather than isolated crimes.

International organizations, including the OAS and the UN, have quietly urged Mexico to ensure safe elections; Mexico’s government has promised investigations but concrete action has been slow. In the meantime, local voices linger: as one councilor put it, “We are fighting to assert democracy, it hurts a lot that this happens in our country,” paraphrasing President López Obrador’s own words. The real test will come on election day and in its aftermath ,whether Mexicans can stand up to the cartels’ challenge at the ballot box.

Citations and references

All citations in this investigation correspond to verified sources gathered during extensive research across multiple continents and databases. Full documentation available upon email to support the accuracy and verifiability of all claims made.

- El País (Apr. 27, 2024), “Mexico is heading towards its most violent election ever, with 30 candidates murdered, 77 threatened and 11 kidnapped”

- EL PAÍS (Apr. 14, 2024), “Chiapas, captive territory”

- Reuters (May 25, 2022), “Politicians’ mafia past stirs anger ahead of Sicily election”

- Reuters (May 23, 2021), “Bloody Mexican election campaign exposes chronic security woes”

- Crisis Group (June 23, 2023), “Mexico’s Forgotten Mayors: The Role of Local Government in Fighting Crime”

- Wilson Center (Mar. 13, 2024), “Political Violence in Mexico’s 2024 Elections: Organized Crime Involvement”

- Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED, July 2024), “Five key takeaways from the 2024 elections in Mexico”

- ACLED (2023), “Special Issue on the Targeting of Local Officials: Brazil”

- Amnesty International (May 6, 2010), “Philippines: Election marred by political killings”

- Reuters (June 14, 2010), “Mexico drug gangs threaten, kill election hopefuls”

About Our Investigative Services

Seeking to expose corruption, track illicit financial flows, or investigate complex criminal networks? Our specialized investigative journalism agency has proven expertise in following money trails, documenting human rights violations, and revealing the connections between organized crime and corporate malfeasance across Africa and beyond.

Partner With Us for Impactful Change

Ready to drive transparency and accountability in your sector?

Our investigative expertise and deep industry networks have exposed billion-dollar corruption schemes and influenced policy reform across Americas.

Whether you’re a government agency seeking independent analysis, a corporation requiring risk assessment and due diligence, or a development organization needing evidence-based research, our team delivers results that matter.

Join our exclusive network of premium subscribers for early access to groundbreaking investigations, or contribute your expertise through our paid contributor program that reaches decision-makers across the continent.

For organizations committed to transparency and reform, we also offer strategic partnership opportunities and targeted advertising placements that align with our mission.

Uncover unparalleled strategic insights by joining our paid contributor program, subscribing to one of our premium plans, advertising with us, or reaching out to discuss how our media relations and agency services can elevate your brand’s presence and impact in the marketplace.

Contact us today to explore how our investigative intelligence can advance your objectives and create lasting impact.