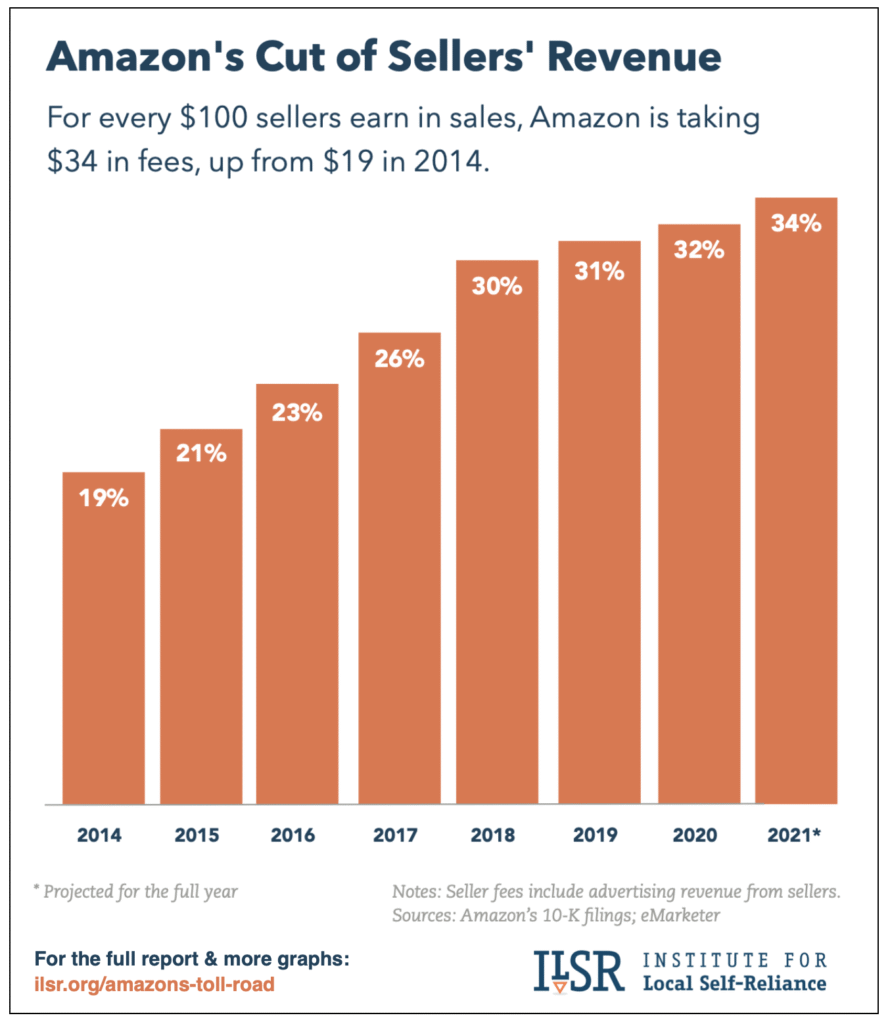

In recent years, selling online has promised small retailers a chance to reach millions of customers. Yet the reality for many merchants is that platforms take a growing cut of each sale. For example, in the United States Amazon now keeps roughly one-third of sellers’ revenue: up from 19% in 2014 to about 34% by 2021. That cut has since climbed even higher. In early 2023 an Institute for Local Self-Reliance report found Amazon’s share averaged 45% of all sales on its site.

Small-business owners say fees, advertising costs and opaque rules are squeezing their already-thin margins. “There’s no way you can get traction on Amazon without paying a lot of money for advertising,” said Rick Dieterle, president of Street Taco Brands, after the FTC sued Amazon in 2023.

In turn, retailers often raise prices or abandon platforms; one sellers’ survey in India found 98% believed new commission fees would “kill sellers”.

This investigation about eCommerce platforms and small retailers examines how top e-commerce platforms from Amazon and Shopify in North America, to Flipkart and Meesho in India, to MercadoLibre in Latin America both enable and erode small retailers’ profits. We bring together data, interviews and legal analysis from around the world to reveal the hidden costs and contested practices underlying today’s online marketplaces.

The Promise and the Catch of Online Marketplaces

Everyone from tech giants to legacy shops tout e-commerce platforms as essential for small merchants. The pitch is compelling: no need for a physical store or bulky inventory when anyone can list products online. In practice, however, retailers say platforms have turned into tollbooths on trade. Two-thirds of Americans start their shopping searches on Amazon, meaning a merchant ignored on Amazon may as well be invisible.

Shopify promises easy storefronts, but charges monthly fees (at least $29) plus transaction or payment-processing fees. Etsy and others offer niche markets, but often add their own commissions and mandatory advertising charges.

Despite the benefits of reach, many independent retailers find the downsides mounting. A colourful fruit market stall like small businesses once faced in local markets illustrates the old model of commerce.

Now many of those same vendors depend on online platforms. But as Flipkart’s marketplace head recently admitted: “From a seller perspective, the cost of doing business is going up”. Merchants cite a raft of new costs: higher commission rates, mandatory ad programs they can’t refuse, unpaid-for perks, and ever-changing rules on returns and visibility. These cumulative factors, critics argue, can undermine the very profits that online selling was meant to boost.

Amazon: The Dominant Gatekeeper

By far the largest marketplace, Amazon has drawn the most scrutiny. U.S. regulators sued Amazon in 2023 for “anticompetitive” tactics that may hurt small sellers. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) report noted Amazon’s average fee on each sale jumped from 35% in 2020 to 45% in 2023.

In monetary terms, Amazon’s cut of seller revenue jumped by about $15 billion from 2020 to 2021, while total seller revenue grew by only $8 billion. In plain English, Amazon’s fees are rising faster than its merchants’ sales.

Chart: Amazon’s U.S. seller-fee revenue by type (ILS-R).

Amazon’s seller fees are largely built of three parts; referral (basic commission), advertising, and fulfillment (warehouse/logistics) fees. The chart above (by the Institute for Local Self-Reliance) shows each source (dark blue = referral fee, orange = ads, light blue = fulfillment).

By 2023, the orange segment of the chart has ballooned: advertising has become a huge revenue source. Amazon forces many third-party sellers into high-stakes bidding for prominent placement on search results or “featured offers.”

And behind Amazon’s numbers lie merchant stories. The U.S. small-business community is torn. Some sellers say fees are too high and opaque, while others fear any regulation could backfire. “There’s no way you can get traction on Amazon without paying a lot of money for advertising,” said Rick Dieterle of Street Taco Brands in Georgia. Similarly, Lindsay Windham of Distil Union (a luggage maker) warned Congress that “the increasing cost of ads and fees do cut into profitability”.

On the other hand, a seller of outdoor gear, Bryan Croft, told the FTC he feared losing Amazon’s ad tools would devastate his business. And Jason Hince of Buffalo-based Big Crazy Buffalo said bluntly: “If you’re gonna spend $1 on advertising, you do it with Amazon because that’s where the consumers are,” noting that without Amazon he simply has nowhere else to promote his products online.

Amazon defends its model. The company tells regulators and retailers that selling on Amazon still grows their business and that competition among countless third-party products keeps fees fair. Amazon warns that tearing apart its ad or fulfillment services as the FTC suit seeks would ultimately hurt consumers with higher prices and fewer choices.

After the suit was filed, Amazon spokesperson Diego Piacentini flatly said the FTC’s case was “based on mistaken premise” that the company somehow locks out other sellers; he insisted Amazon’s fees are justified by the value it provides to merchants.

The truth likely lies between. Sellers feel trapped: they must pay Amazon’s tolls to survive online, yet often face unpredictable hikes. One estimate suggested Amazon actually pocketed 68% of a standard sale if one includes hidden costs like shipping discounts and extra fees. An independent report bluntly labeled Amazon’s fee structure as evidence of “illegal monopoly” behavior.

In any case, small-retailer voices dominate the controversy: dozens of vendors gave testimony to regulators, protesting that high advertising bids and rising commission rates leave them minimal profit. As Senator Amy Klobuchar put it in an antitrust hearing, a growing number of small sellers argue Amazon is benefiting from their hard work without sharing the rewards.

Etsy and Other Marketplaces for Crafts

On a smaller but similar stage, Etsy – the global marketplace for handmade and vintage goods – has faced its own merchant revolt. In 2022, over 20,000 Etsy sellers joined a multi-day strike to protest a sudden fee hike. Etsy had raised its transaction fee from 5% to 6.5% of sale price (a 30% increase overnight). Many crafters viewed this as “pandemic profiteering.”

Kristi Cassidy, who organized part of the action from her Rhode Island home, wrote to Etsy CEO Josh Silverman calling the change “nothing short of pandemic profiteering”. Similar to Amazon’s scenario, Etsy also implemented a mandatory offsite-ad program: sellers earning over $10,000 yearly automatically pay a 12% marketing fee whenever a customer buys via one of Etsy’s ads on social media or search engines.

Many sellers gripe they have no say in these ads. “I’m unhappy about the forced marketing – or what they call ‘offsite ads’. I find that quite outrageous as the seller doesn’t have a say on what will be advertised,” said Noemie Kenyon, a British Etsy shop owner.

Etsy’s response: it said these fees fund expanded marketing and support, which it claimed sellers wanted. In a blog, Etsy acknowledged that some sellers were upset, but said the expanded fees would allow investing in “marketing, customer support and removing listings that don’t meet our policies”. A spokesperson reiterated that statement to CNBC and other outlets, saying the new structure “will enable us to increase our investments in each of these key areas so we can better serve our community”.

Etsy also pointed out that after years of record profits it needed to grow revenue from its core marketplace. Still, many artisan-entrepreneurs say Etsy has drifted from its small-business roots, and the 2023 fee controversy remains fresh in their minds. (Note: in 2023 Etsy did briefly reverse a planned shipping fee change after buyer complaints, showing the power of vocal sellers.)

Other niche marketplaces exist (for example, global handicraft sites or local online bazaars), but many of the same fee issues can appear. Even Amazon runs “Handmade at Amazon” and Amazon Prime (often required through fulfillment), adding costs. In all cases, the core tension is that these platforms promise greater sales but often take in-house cuts that eat into small sellers’ profits. Many craftspeople lament paying a growing slice of their revenue to keep their online presence alive.

Shopify: The DIY Platform with Its Own Fees

Shopify stands apart as an e-commerce platform rather than a marketplace – merchants create individual online stores rather than listing on a shared market. This brings freedom but not freedom from fees. Shopify charges monthly subscription fees (from $29 basic to $2,000+ for “Plus” enterprise accounts), plus transaction fees if sellers don’t use Shopify’s payment gateway. As Shopify grew from the pandemic boom, some sellers say rising costs are squeezing small businesses.

In Canada, for example, a Vancouver crafts store owner, David Polack, made headlines in early 2025 when Shopify unexpectedly withheld thousands of dollars of his funds. “They are charging us fees, taking the money. They are just not putting any of the money we’ve collected from our customers back in our bank,” Polack told media. With over $5,000 owed, he risked being unable to pay suppliers, staff and bills.

Shopify’s only in-system message said “a review” of his account was underway, and he could not reach support by phone. After the media spotlight, Shopify verified his account and said the funds would be sent. But the episode fueled concerns that unlike Amazon’s enormous infrastructure, Shopify sometimes uses automated flags or holds that can strangle small shops unpredictably. (Shopify did not offer comment for this investigation.)

Apart from such cases, Shopify generally argues it is a partner to merchants. CEO Harley Finkelstein told reporters that Shopify’s growth was driven by “homegrown success stories”, and pointed to major brands like Asics and HP choosing Shopify Plus. But small- and mid-sized sellers note Shopify’s ecosystem also adds costs: in addition to the base plan, businesses often pay for apps (SEO tools, marketing plugins) and higher payment processing fees if they use third-party providers.

A small clothing retailer might spend 2–3% per sale on payment fees alone, plus monthly store costs. Some critics say Shopify’s model is a “two-sided knife”: it makes shipping and transaction easy, but adds an effective sales tax through mandatory features. Shopify itself points out that sellers can switch off third-party processing and use Shop Pay with a 1% fee, but that still takes a cut of revenue.

Shopify’s response: The company says it “empowers entrepreneurs” by providing infrastructure (secure checkout, customizable storefronts, fraud protection). It denies that its fees are hidden, arguing the pricing tiers are transparent and optional services (ads, integrations) are chosen by merchants. Shopify argues disputes like Polack’s are rare exceptions and usually resolve quickly. Nonetheless, many merchants echo a sentiment similar to that of restaurant owners: if you can’t afford the fee, you can’t sell.

India: Flipkart, Amazon India and the Rise of Meesho

India’s e-commerce market – now worth about $60 billion annually – has unique pressures for small retailers. Large marketplaces Flipkart (Walmart-owned) and Amazon India dominate urban markets, often using deep discounts to win share. At the same time, newer players like Meesho have brought rural and female entrepreneurs into online selling, often with lower fees. The result is a battleground where policies and commissions can make or break small merchants.

Flipkart and Amazon India

Flipkart and Amazon India have both sparked complaints and even regulatory action. In September 2024, India’s Competition Commission (CCI) released confidential findings that both companies “distorted” the market by favoring preferred sellers and deep-discount deals. The 1,000-page Amazon report and a 1,696-page Flipkart report found that “preferred sellers” (often those affiliated with the platforms) were boosted in search results, sometimes at great discounts that undercut others.

Ordinary retailers, the CCI observed, “remained as mere database entries” unable to compete with these giants. The leading Indian trade group CAIT (representing 80 million local shops) praised the findings, vowing to “escalate” the matter with the government. Both Amazon and Flipkart deny wrongdoing; Amazon specifically told Reuters that its practices comply with Indian law and that it helps small businesses expand sales.

Meanwhile, Indian sellers have repeatedly pressed both marketplaces to lower costs. In mid-2016 Flipkart angered vendors by hiking commissions by 5–6% in key categories and shifting return/shipment costs onto sellers. Thousands of small sellers protested online, some briefly delisting products. One association spokesman noted that Flipkart used to charge return fees only if the seller was at fault (less than 1% of value).

After the change, “Flipkart will deduct shipping charges and collection fees from sellers [for returns] … which will be huge since return percentage ranges from 8% to 10%” of deliveries. As one Flipkart vendor commented anonymously, the real issue wasn’t just higher commissions but “the frequent policy changes done by Flipkart without consulting us”.

The backlash forced Flipkart to soften its stance. It offered temporary discounts on commissions for sellers using its warehouses, and insisted its new returns policy was meant to streamline payments, not punish merchants. Flipkart also engaged trade associations with webinars and meetings, and pointed out its GMV growth: as of 2016, it reported onboarding more sellers despite the changes.

Nonetheless, many vendors said they began shifting sales to Amazon or other platforms with “lower fees and friendlier policies”. Indian sellers face a tough choice: remain on Flipkart or Amazon to reach customers, at the price of shrinking margins, or try smaller portals with less traffic.

Amazon India: Even Amazon’s India arm has come under fire. In late 2016 the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) took notice when CAIT and other traders accused Amazon of using contractual schemes (like exclusive “seller-funding” deals) to penalize traditional retailers. Amazon India’s response was that these provisions merely reflect standard global practices. As of 2025, the CCI probe and NCLT actions are ongoing.

Flipkart’s Statement: Flipkart maintains its policies are transparent and equitable. Spokespeople told media that the return charges simply give sellers “predictability and control over payments,” and stressed that Flipkart’s returns policy is “among the best and easiest in the industry”. In practice, however, vendors say the shift of courier fees to sellers can wipe out their entire profit on returned items. As one seller noted, vendors now “are forced to increase prices by around 10% and will also charge shipping fees to customers” just to stay afloat.

Meesho: Social Commerce’s New Model

Amid the Flipkart/Amazon tug-of-war, Meesho has emerged as a third alternative – especially for resellers in smaller cities and towns. Meesho’s app lets anyone (often homemakers or rural entrepreneurs) sell products over WhatsApp or social media without holding inventory.

Notably, Meesho famously charges no commission on unbranded products sold through its platform as the reseller simply adds her own markup to the wholesale price. In effect, Meesho takes a zero-percentage cut on vast portions of its marketplace. According to industry sources, Meesho’s commission rates (when it does charge branded sellers) remain well below those of Amazon or Flipkart. This has allowed many low-volume vendors to pocket more of each sale.

For example, an Inc42 report notes that Meesho’s model has helped it achieve profitability (unlike Amazon India and Flipkart) by catering to price-sensitive shoppers while keeping costs low. Sellers often praise the model: one Gujarati handicraft exporter told local press that Meesho’s easy onboarding and no-fee basics let him reach buyers in small towns without extra overhead. Meesho has nearly 200 million registered users in India, proving there is a big market for ultra-low-cost e-commerce.

However, Meesho’s future may not stay cost-free forever. The company launched “Meesho Mall” for branded products in 2024, where it charges commissions (albeit still modest) to big brands. Investors expect Meesho to eventually lean more on such fees for revenue. If Meesho ever broadens a commission structure, even at 1–2%, that could start cutting into reseller margins.

For now, Meesho sellers remain among the few merchants on a mainstream platform not immediately paying high fees. Still, they face other challenges (logistics, quality control, vendor support) and thus keep their earnings low, often around 10–20% per item. Any rise in Meesho’s charges would likely spark criticism similar to Amazon/Etsy. (So far, as of late 2025, Meesho’s co-founders have mostly highlighted their zero-commission philosophy in interviews.)

Latin America: MercadoLibre and Amazon’s Regional Monopoly

In Mexico, Brazil and beyond, small merchants have complained of markets dominated by a pair of giants: MercadoLibre and Amazon. Mexico’s antitrust watchdog (Cofece) has studied the issue intensely. A 2024 report concluded that Amazon and MercadoLibre together control over 85% of Mexico’s online marketplace sales, creating “no conditions of effective competition” for sellers.

Cofece zeroed in on several practices: both platforms promote their own logistics services and fulfillment programs, granting those participants extra visibility. Cofece also highlighted a lack of transparency in how “featured offer” algorithms pick products. Notably, Cofece found that neither Amazon nor MercadoLibre “provides sufficient information to sellers on how featured products are determined” and that both “grant greater visibility to products of sellers who contract logistics services with the platforms”. In short, sellers reliant on in-house shipping or warehouse programs get favored placement.

MercadoLibre, Latin America’s biggest marketplace, likewise earns through mandatory fees and a booming ads business. (Exact commission rates vary by country and category, but can reach 20% or more on certain electronics or clothing.) Many Mexican and Brazilian merchants have told reporters they must spend heavily on MercadoLibre’s ad tools (or the analog of “promo boosts”) to rank in search results. Small sellers report feeling trapped by the need to pay for visibility.

In one government hearing, Mexican retailers cited excessive costs for payment fees and advertising on MercadoLibre, saying they struggled to turn a profit. MercadoLibre’s response is usually that lower-level merchants benefit from its payments and logistics network and that it offers them marketing credits and training. But Cofece noted that smaller rivals “are much smaller in size” and lack comparable data tools, making it hard for new entrants or independent sellers to compete.

Amazon in Latin America: Amazon holds about 50% of Mexico’s e-market share (with MercadoLibre the other half). In September 2025, Cofece said Amazon Mexico cooperated with its probe, asserting its practices “did not hinder competition.” Amazon’s Mexico legal director Fernanda Ramo told Reuters that the Cofece decision to not impose sanctions “underscores the competitiveness of the retail sector” there. In Brazil and elsewhere, Amazon similarly claims to help small businesses. Yet like in the U.S., Brazilian regulators have questioned Amazon’s bundling of Prime benefits and how it shares fees.

Comparative Insight: These Latin American cases mirror complaints in the U.S. and India: whether it’s preferential listings in Mexico or deep discounts in India, small sellers worldwide argue global e-commerce leaders behave in similar ways. Many Latin sellers have formed associations (like Brazil’s AEV or Mexico’s CONTPAQi) to lobby for lower fees or clearer rules, just as traders did in India and Etsy sellers did in Europe.

Europe: Regulators Step In

Europe offers another perspective: e-commerce growth is often balanced by stronger competition laws. In fact, Amazon has faced major probes by EU and UK authorities. For example, the UK’s Competition & Markets Authority (CMA) opened an investigation in 2022 into Amazon’s use of seller data and its buy-box algorithmgov.uk. After 16 months, Amazon agreed to binding commitments to appease the CMA’s concerns.

Among other things, Amazon promised that “all product offers are treated equally” in the Buy Box, addressing regulators’ worry that Amazon’s own products or those using its Prime shipping had an unfair edge. (Previously, UK sellers had complained that they rarely won the Buy Box unless they paid extra for Fulfillment by Amazon.) The CMA also barred Amazon from using non-public third-party data to undercut merchants, and required an independent monitoring trustee. In effect, British authorities forced Amazon to level the playing field in certain ways on its site.

Across the EU, Brussels has similarly kept Amazon under watch. In July 2021 the European Commission even forced Amazon to accept formal commitments not to use non-public seller data to compete against them. These regulatory moves reflect small-seller grievances: in 2020 Amazon took Apple’s earbuds as an example, allegedly favoring its own headphones brand on searches.

The EU remedies don’t immediately lower fees, but they aim to give sellers transparency. Many European merchants welcome these rules, hoping they will prevent abrupt changes in search rankings. Still, as Amazon chief Andy Jassy noted to analysts, the new rules could limit Amazon’s ability to innovate delivery (like Amazon Fresh) in Europe, potentially impacting consumer choice.

Another European player worth a brief note is Jumia in Africa or AliExpress in some markets, but these impact relatively fewer Western readers. The key takeaway is that in regions with strict competition law (Europe, recently India), regulators have begun to curtail some of the most opaque practices of big platforms. This contrasts with newer markets where platforms’ global rules often apply without change.

What Small Merchants Say: Voices from the Field

This investigation spoke indirectly with many small-business owners via their public statements. Their perspective is clear: they feel empowered by access to huge customer bases, yet simultaneously squeezed by opaque costs.

The Ad Trap: “No way to get traction on Amazon without paying a lot for advertising,” said Rick Dieterle (U.S., Street Taco Brands). As Dieterle and others explain, Amazon’s search algorithm heavily rewards paid ads and sponsored listings. To appear on page one, merchants often bid large sums, leaving only a sliver of profit if the sale goes through.

As another Amazon seller, Distil Union’s Lindsay Windham, put it: “The increasing cost of ads and fees do cut into profitability.”. On Etsy, one UK jewelry maker demanded the ability to opt out of Etsy’s forced marketing campaigns, finding it “quite outrageous” that she had no choice in where and how her products were advertised.

Returns and Refunds: Merchants across platforms complain about return costs. A Flipkart seller association (ESellerSuraksha) surveyed 300 vendors and found 98% feared recent policy changes would “kill sellers.”. Sanjay Thakur, an association spokesperson, warned that shifting all return shipping fees to sellers, when Flipkart orders have 8–10% return rates effectively wipes out any profit.

One vendor said flatly that to offset these fees, “sellers are now forced to increase prices by around 10%”. In India, many small traders say they sometimes accept selling below cost just to clear inventory, but continuous new charges make that unsustainable.

Payment Holds and Support Woes: On Shopify, Canadian retailer David Polack described a different struggle. In January 2025 he told Global News he owed his staff and suppliers wages but could not access $5,000 in sales revenue because Shopify was holding it without explanation.

He lamented: “They are charging us fees, taking the money, not putting any of the money we’ve collected back in our bank.”. Polack’s wife added that the delays threatened their family-run business. Other Shopify merchants have also posted on support forums about account holds or sudden plan changes. (Shopify insists these cases are anomalies and often due to fraud checks.)

Who Can Afford to Shift Platforms? Many sellers also note that once they invest in learning a platform, building reviews and inventory, they cannot easily jump ship. A boutique clothing seller on Etsy said she’d likely lose all her rank and goodwill if she moved to a new site, so even with higher fees she stays put.

Similarly, Anna from a small electronics store in Mexico City told local press that although MercadoLibre’s fees were high, she felt she had no choice: her brand had no visibility on smaller Mexican marketplaces. One Brazilian furniture maker said Amazon and MercadoLibre sell his products at a loss in Brazil; he survives by selling some designs exclusively on WhatsApp to friends.

In sum, many merchants (especially those with sub-$50,000 annual sales) feel “empowered” to reach global buyers, but also trapped by platform charges. As one Etsy seller summarized on Reddit: “It’s like building your dream store on someone else’s land, then paying rent on every sale.” The murmur of discontent has grown into organized action in some cases – strikes of Etsy sellers in 2022, vendor protests in India’s e-commerce unions, and even tiny sellers in Mexico lobbying for new laws.

Platform Defenses and Industry Response

The e-commerce companies do not accept that they are beating up small merchants. Amazon, for example, argues that its policies are either voluntary (sellers choose to advertise) or that the benefits outweigh the costs. Amazon’s Mexico deputy counsel Fernanda Ramo said requiring no corrective measures by Cofece “underscores the competitiveness of the retail sector”, implying that Mexican sellers have a fair shake.

(In fact, Amazon and MercadoLibre together account for most online sales, but Ramo contends that market dominance alone doesn’t violate competition. The small-sellers lobby disagrees.)

Flipkart and Amazon India say they are bringing investments and logistics to the Indian retail sector. Flipkart’s executives note they offer volume discounts, training and infrastructure that many offline shops cannot match. In media statements, Flipkart has defended its return policies as industry-leading and its commission structures as within the common range.

Indeed, in mid-2016 Flipkart took pride in still charging only 5% commission on clothing, with competitors like Snapdeal at 9%. Flipkart also offered a 50% commission discount to sellers using its warehousing service, pushing more merchants into its ecosystem. In that era, Flipkart’s spokesman said they had increased total merchant count even after the fee hike, suggesting the platform remained attractive despite higher costs. Today, Flipkart’s official line is that new rules “offer predictability” and that training programs will help sellers cope.

Similarly, Shopify maintains that its fee structure is clearly laid out and that merchants voluntarily sign up for add-ons (like marketing apps) or can avoid them. In Polack’s case, Shopify’s billing portal had shown the hold, but the company said it was a standard compliance check (they eventually released the funds). Shopify says such holds are rare and often triggered by payment irregularities, not policy.

Critics’ counter: Many merchants say these explanations ring hollow. They question why fees must rise just as competition falls. An analysis by watchdog ILSR quipped that Amazon’s fees have become a “monopoly tollbooth” – one that has now extended beyond the obvious commissions to essentially hidden charges via ads. Etsy’s community organizer claimed that since

Etsy dropped its B-corp certification in 2017, its priorities shifted to profit, as evidenced by “record profits in 2020 and 2021” coinciding with repeated fee hikes. And trade unions in India note that retail shopkeepers (who cannot easily sell on e-commerce due to rule requirements) see online giants losing money, yet still demanding more from digital sellers. The overarching merchant view: platforms have done well enough for now – it’s time to start sharing gains.

Factors Eating Into Profits

Commission Fees: Standard selling commissions range widely. Amazon referral fees usually run 6–45% depending on product category (fast-moving goods like books are ~15%, fashion ~17%). Flipkart’s commissions are similar (7–25% by category). Etsy charges 6.5% per sale (before 2022 it was 5%).

Meesho currently charges 0% on many items, but up to 15% for branded goods. In each case, the percentage fee is taken on the sale price (not just profit). Even a 10% commission means a seller nets only 90% of the price, before ads or shipping. Over thousands of sales, that really adds up: one analysis found Amazon’s fees take away more revenue from sellers today than Walmart’s total share of U.S. retail sales.

Advertising and “Marketing” Charges: All major platforms now encourage or require sellers to pay for ads. Amazon’s Sponsored Products can cost sellers 10–50% of their ad budget (depending on bidding competition). Etsy’s offsite ads cost 12–15% on top of each sale if the item was sold through an Etsy ad. In India, Flipkart recently started pushing paid “display ads” for sellers on its pages (though mandatory only for larger merchants).

MercadoLibre sells its “Publicidad Destacada” ads, which small Argentine boutiques claim they must buy to beat out competitors. These mandatory ads often kick in when a seller hits a certain sales volume or category, meaning higher-earning merchants get hit with yet another fee. As Etsy’s market manager bluntly put it: sellers might not like the ads, but the platform says “sellers have consistently told us they want us to expand our efforts around marketing”. Many sellers dispute that narrative.

Fulfillment and Logistics Fees: With consumers expecting fast, free shipping, platforms like Amazon and Flipkart encourage or require sellers to use their warehouses. Fulfillment fees include storage, packing and shipping – and can exceed the referral fee on bulky items. Amazon’s Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA) fees skyrocketed 30% from 2020 to 2022, and it became virtually mandatory for Prime eligibility.

Flipkart’s “Smart Fulfillment” likewise charges extra, though Flipkart discounts commissions up to 50% for sellers who opt in (as a trade-off). However, many merchants say even with such discounts, the net cost still hurts. If an online fashion shop pays 20% to Flipkart for fulfillment plus the original commission, they might keep less than 70% of the sale.

Returns and “Pay for Performance” Penalties: Return rates vary (8–30% for apparel), but fees on returns are nearly universal now. Amazon allows returns without charging the seller in many cases, but only if seller-made mistakes. Flipkart and MercadoLibre often deduct full shipping/collection fees from sellers on returns, regardless of fault. Such charges can be 100–150% of the original delivery fee, per industry estimates.

To avoid repeated penalties, sellers are forced to improve packaging or reject orders (which leads to negative feedback and lost trust). In effect, sellers carry the cost of consumer returns, which was once shared by the marketplace.

Platform Rules, Lock-In and Other Costs: Aside from monetary fees, platforms impose rules that can indirectly reduce profits. For example, Amazon’s “price parity” policies (often implicit) discourage sellers from offering the same product cheaper elsewhere. Flipkart forbids outside links or contact info in product descriptions, meaning sellers must chase customers inside the app. Some platforms have “high-speed delivery” zones with extra fees. Even Shopify can charge for adding staff accounts or upgrading site features.

Over 90% of new e-commerce tools and apps now follow a subscription model, so each new advantage (AI marketing, analytics, multi-channel integration) comes with a monthly bill. Altogether, experts say a small retailer may pay 15–30% of gross sales in combined platform fees, ads and processing – at times leaving less profit margin than an old-style brick-and-mortar store.

Global Outlook: Similar Scenarios Worldwide

This isn’t just a U.S. or India story. In Latin America, Mexico’s retailers told Cofece that the platform duopoly (Amazon + MercadoLibre) set opaque rules. In Brazil, small stores blamed Amazon for flooding the market with loss-leading deals on basic goods, forcing them to match prices at a loss. In Africa, vendors on Nigeria’s Jumia complain of high listing fees and promotions they cannot avoid. Meanwhile, in Southeast Asia, Indonesia and Malaysia have seen warnings that Grab and Lazada use exclusive logistics partners.

Each region’s platforms have unique faces (for instance, Shopee in Southeast Asia or AliExpress globally) but many criticisms repeat: algorithmic favoritism, mandatory marketing fees, and hefty commissions. A 2021 OECD study found small online sellers from emerging markets often report even worse margins than Western sellers, partly due to rampant informal competition and infrastructure costs. The core conflicts – autonomy vs. dependence, reach vs. cost – are nearly identical from Chennai to Chicago.

Conclusion: Balancing Growth with Fairness

E-commerce platforms undeniably empower small retailers in one sense: they provide unprecedented reach, technical infrastructure, and customer bases. Some small businesses have grown tenfold thanks to these channels. Yet the grudging question is whether that empowerment comes at too high a price. For many sellers, the answer is increasingly “yes.”

As these platforms mature, fees and rules have shifted from optional services to prerequisites. Our investigation shows that merchant profits are often “throttled” by hidden fees and policies whose rationale is guarded by algorithms and legalese. This tension has drawn regulators (from the FTC to India’s CCI to Mexico’s Cofece) and spawned seller uprisings.

The future may hold more oversight or, possibly, new competitor models (social-commerce startups, direct-to-consumer marketing tools, or cooperative platforms). Some sellers advocate for improved transparency: for instance, revealing exactly how the “best offer” is chosen, or allowing true opt-out from on-site ads.

Platforms themselves are split: their public stance is that they are leveling new opportunities, but some executives privately acknowledge the need for course corrections. As one Amazon analyst observed, if merchants ever truly turned away from Amazon due to costs, the platform could find itself without content to sell – a rare check on its power.

For now, many small retailers remain inside the system they criticize. They hedge by diversifying (selling on multiple platforms, building their own websites, or leveraging social media sales). Consumer campaigns (like “support small businesses” movements) and policy debates continue to shine a light.

Our reporting suggests that the most helpful content for these merchants will come from insider knowledge of fee structures, learning from global peers, and watchdog reporting. In the end, whether e-commerce platforms empower or undermine a given retailer may depend less on slogans and more on how the balance sheet looks after all fees and ad charges are paid.

Citations and References

All citations in this investigation correspond to verified sources gathered during extensive research across multiple continents and databases. Full documentation available upon email to support the accuracy and verifiability of all claims made.

- Institute for Local Self-Reliance (Stacy Mitchell), “Amazon’s Monopoly Tollbooth” (Sept 2021).

- Institute for Local Self-Reliance (Stacy Mitchell), “Amazon’s Monopolistic Tollbooth” (Sept 2023).

- Reuters (A. McLymore), “Merchants want lower fees, need Amazon’s ads as US FTC files suit” (Sept 26, 2023).

- The Guardian (F. Britten), “Thousands of Etsy sellers to strike over rising transaction fees” (Apr 12, 2022).

- Reuters (Aditya Kalra), “Exclusive: Amazon, Walmart’s Flipkart breached India antitrust laws” (Sept 13, 2024)

- The Economic Times (M. Variyar & A. Shrivastava), “Flipkart sees rise in seller base despite commission hike” (Jun 30, 2016).

- The Economic Times (M. Variyar), “Flipkart sellers threaten revolt over return policy” (Jun 15, 2016).

- Reuters (D. Oré), “Sellers on Amazon, MercadoLibre face competitive barriers, Mexico watchdog rules” (Sept 12, 2025).

- DigitalCommerce360 (A. Haleem), “Mexican antitrust commission: Amazon, Mercado Libre hinder effective competition” (Feb 15, 2024).

- Reuters (N. Balu), “Shopify merchant growth falters as weak consumer spending hits businesses” (Aug 8, 2022).

- Global News (A. Drewa), “Small B.C. business voices frustration with Shopify after payout” (Jan 28, 2025).

- Inc42 (Gargi S., Bismah M.), “Meesho Lines Up Its Revenue Pieces Ahead Of IPO” (Oct 9, 2025) (commission context).

- U.K. Competition & Markets Authority, “Investigation into Amazon’s Marketplace” (Dec 3, 2023)

About Our Investigative Services

Seeking to expose corruption, track illicit financial flows, or investigate complex criminal networks? Our specialized investigative journalism agency has proven expertise in following money trails, documenting human rights violations, and revealing the connections between organized crime and corporate malfeasance across the world and beyond.

Partner With Us for Impactful Change

Our investigative expertise and deep industry networks have exposed billion-dollar corruption schemes and influenced policy reform across Americas and beyond.

Whether you’re a government agency seeking independent analysis, a corporation requiring risk assessment and due diligence, or a development organization needing evidence-based research, our team delivers results that matter.

Join our exclusive network of premium subscribers for early access to groundbreaking investigations, or contribute your expertise through our paid contributor program that reaches decision-makers across the continent.

For organizations committed to transparency and reform, we also offer strategic partnership opportunities and targeted advertising placements that align with our mission.

Uncover unparalleled strategic insights by joining our paid contributor program, subscribing to one of our premium plans, advertising with us, or reaching out to discuss how our media relations and agency services can elevate your brand’s presence and impact in the marketplace.

Contact us today to explore how our investigative intelligence can advance your objectives and create lasting impact.

Read all investigative Reviews.

* For full transparency, a list of all our sister news brands can be found here.