The global tech boom has a grim underside: the dangerous, often deadly mining of cobalt in Africa. Cobal, a critical component in lithium-ion batteries is mined predominantly in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), which supplies roughly 70% of the world’s cobalt.

Yet this “blue gold” comes at the expense of hundreds of thousands of impoverished miners, including many children, who work under perilous conditions for a few dollars a day.

This investigative report about Exploitation of African Cobalt Miners uncovers how multinational tech companies (Apple, Tesla, Samsung, etc.) have profited from these conditions, and how activists, NGOs and governments are reacting. It draws on field investigations, legal filings, and expert analysis to document a pattern of exploitation spanning the DRC, Zambia, Madagascar and beyond.

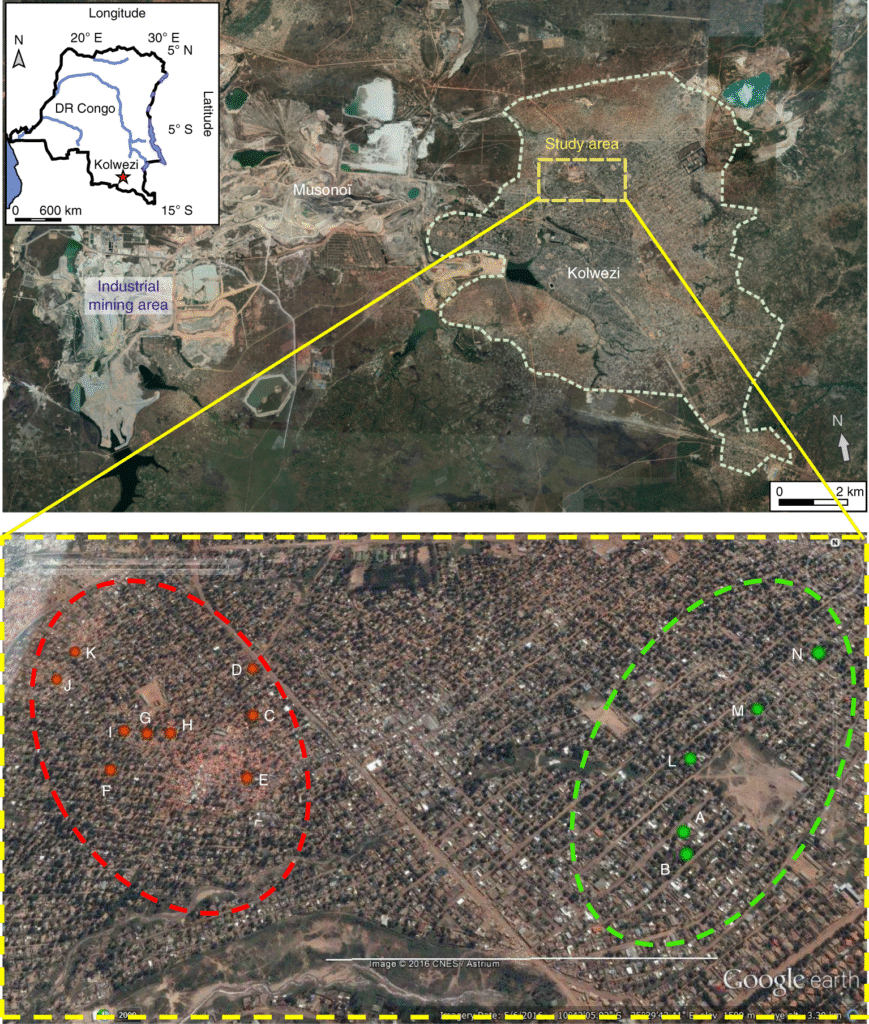

Cobalt mining is concentrated in Congo’s Katanga (Haut-Katanga and Lualaba) provinces, where both industrial and informal mines proliferate. Artisanal miners often working illegally extract roughly 15–30% of the DRC’s cobalt, sometimes under the control of armed groups or corrupt officials.

These informal mines employ 150,000–200,000 people directly, with about a million dependents in mining communities. Children as young as 7 have been documented working 10–12 hours per day in narrow tunnels, carrying heavy loads of rock. Such conditions have led to frequent accidents (an estimated 80 artisanal miners died in southern DRC between Sept 2014 and Dec 2015 alone) and serious health issues from dust and toxins.

Cobalt’s allure is driven by relentless demand for electronic devices and electric vehicles. Global cobalt demand is projected to quadruple by 2030 as renewable-energy and EV markets expand. Yet consumers rarely hear about the origins of the cobalt in their gadgets. As Amnesty International’s Mark Dummett put it, “[t]he glamorous shop displays and marketing of state-of-the-art technologies are a stark contrast to the children carrying bags of rocks, and miners in narrow manmade tunnels risking permanent lung damage”.

According to a 2016 Amnesty/Afrewatch report, major electronics brands including Apple, Samsung and Sony “are failing to do basic checks” to ensure their cobalt is not sourced from child labor. Cobalt mined by young diggers in Congo often ends up at Chinese processors (such as Huayou Cobalt’s subsidiary CDM) and from there in batteries sold to Apple, Microsoft, Samsung, Sony, Daimler, Volkswagen and others. None of those companies has provided sufficient tracing to prove a clean supply chaina.

Harrowing Lives in the Mines

A young miner carries sacks of cobalt ore out of a Congolese pit (Photo: Sebastian Meyer, 2018). Children and “creuseurs” (informal diggers) routinely brave underground tunnels for pitiful pay. One miner’s 2019 account (2nd-hand via a Guardian report) is chilling: “I would spend 24 hours down in the tunnels. I arrived in the morning and would leave the following morning,” said 14-year-old Paul, an orphan who worked for about $1–2 a day.

In an interview, miner Ziki Swazey explained that from age 11 he had never attended school because he spent each day washing cobalt ore in blistering heat, returning home with only a few dollars to care for his sick grandmother.

The work is primitive and dangerous. Laborers often lack even basic gear: no gloves, masks or helmets. Journalists found miners wedging themselves into hand-dug shafts with sandbag supports, hacking ore with rebar scraps, and carrying metal buckets filled with ore on their backs.

A 2019 Guardian investigation recounted the story of Bisette and her nephew Raphael: as a child, Raphael had attended school until the family ran out of money. By age 12 he was working as a surface digger; by 15 he was tunneling under a mine site owned by a foreign company. In 2018 the tunnel collapsed and Raphael was suffocated to death underground. Bisette’s grief is a harsh reminder of the human cost: “I prayed to God: ‘Please, let my son be alive,’” she said, only to learn there were no survivors. She and dozens of other families say they were unaware their children had been working at those industrial sites.

Mining experts emphasize that children and other artisanal workers are technically barred from official industrial mines in Congo. But lax oversight and collusion allow this labor to continue. Many artisanal sites are in remote areas where even the Congolese state has little presence; armed groups sometimes “provide security” or protection to miners for a cut of the yield.

Ongoing corruption skews the entire supply chain: cobalt extracted illegally is frequently “laundered” through official channels. Local officials, police or soldiers have been caught purchasing cobalt from unauthorized pits and sending it through ministry certification. In short, a significant portion of Congo’s cobalt (aside from known industrial mines) may be surreptitiously funneled out to the global market without traceable documentation.

Tech Giants in the Spotlight for Exploitation of African Cobalt Miners

Tech giants find themselves at the center of scrutiny because their products embed this problematic cobalt. Lawsuits and NGO reports accuse companies of turning a blind eye. In December 2019 a U.S. class-action suit (filed by International Rights Advocates) named Apple, Alphabet/Google, Dell, Microsoft and Tesla as defendants, representing families of 14 Congolese children killed or mutilated in cobalt mine accidents.

The complaint argues these firms “aided and abetted” the abusive mining conditions because their devices depend on Congo’s cobalt. Lead counsel Terry Collingsworth, a veteran human-rights lawyer, warned that he had “never seen such extreme abuse of innocent children on a large scale,” and insisted, “This astounding cruelty and greed need to stop”.

Renowned researcher Siddharth Kara (who helped uncover these cases) lamented that tech companies were “enriching themselves at the expense of the most vulnerable children of the Congo”.

In response, the companies have largely denied wrongdoing. Apple and others insist they audit suppliers and only use smelters certified free of conflict, while Tesla points to its supplier codes. However, independent investigations have found gaps: in 2016, when Amnesty International and Afrewatch asked 16 multinationals about their DRC cobalt, one admitted a link, four were unsure, six were “investigating,” and five flatly denied sourcing DRC cobalt despite evidence to the contrary.

No firm provided enough data to confirm exactly where their cobalt originated. As Afrewatch’s Emmanuel Umpula observed, it is “a major paradox of the digital era” that the world’s richest tech firms can sell high-end devices while refusing to fully disclose their raw material origins.

While Apple and Google have garnered headlines, other big names loom large. Samsung, the world’s largest smartphone maker was specifically called out by Amnesty for failing to ensure no child-labor cobalt enters its batteries. Sony and Microsoft were likewise mentioned.

On the automotive side, Tesla’s reliance on cobalt has been criticized (though the company seeks cobalt-free battery chemistries), and legacy automakers like Volkswagen and Daimler have also been identified as end-users of batteries potentially containing Congolese cobalt.

Chinese firms dominate upstream: Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt (through Congo Dongfang Mining) processes a large share of artisanal ore before sending it to battery-material firms in China and Korea. Thus, the final products of many major tech and auto brands can be (in effect) traced back to Congo’s creuseurs.

Voices of Activists and Workers

A Congolese artisanal miner ties a sack of cobalt, 2018 (Photo: S. Meyer). Activists and mine victims speak out. Auguste Mutombo, a Congolese human-rights worker, helped gather evidence for the lawsuit. After details became public, Mutombo received dozens of death threats and was forced to flee to Zambia with his family for safety.

He warned that protesting these abuses had become dangerous: “I have never seen such aggression and threats in my whole life,” he said. Mutombo’s story illustrates the chilling environment: those who expose mining abuses risk retaliation by local elites or armed actors.

Meanwhile in the DRC, families continue to grieve. Bisette, the guardian of the boy killed in the tunnel collapse, bravely recounted her story to researchers despite fears. Similarly, other child miners have shared their experiences: one 14-year-old orphan named Paul described hauling 50-kg loads through dim tunnels for only about $2 a day.

The United States Department of Labor confirms these accounts: in 2014, UNICEF estimated about 40,000 children were working in DRC mines, many in cobalt pits. The international press has documented children operating in Kolwezi’s and Lubumbashi’s cobalt fields, often comparing it to slavery or modern feudalism.

Labor experts emphasize that these children are victims of systemic poverty and weak governance. The DRC’s own mining laws forbid under-18s from mining, but law enforcement is minimal. Many families simply cannot afford schooling or basic needs.

As one legal expert noted, the coercive powerlessness of miners (child or adult) is treated as an “impediment to immense profits” by those higher up the chain. In practice, companies that purchase cobalt often do so through layers of middlemen, losing sight of the conditions at the mine. Survivors and relatives interviewed by NGOs consistently demand accountability; but for now, most rely on international lawyers and courts.

Supply Chain and Global Impact

dol.govNearly all Congolese cobalt (over 90%) is ultimately exported to China for refining. According to U.S. data, in 2020 the DRC exported about $2.36 billion in cobalt, of which $2.17 billion went to China. Chinese companies whether state-owned or private operate or invest in most of the country’s mines, blurring the line between local and foreign control.

This means consumers in America, Europe and Asia all end up paying for Congolese minerals tainted by child and forced labor. When cobalt from different mines is blended in refineries, “tainted” ore cannot be separated; thus any use of artisanal cobalt taints an entire batch.

Beyond the DRC, other African countries are stepping into the picture. Zambia has copper-cobalt prospects. Firms like Anglo American and the Silicon Valley start-up KoBold Metals (backed by Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos) are exploring Zambian cobalt-copper projects.

To date, Zambia’s mining is industrial-scale and largely formal, so it has not seen the widespread child labor reported in the DRC. However, labor rights activists note that mines in Zambia (including Chinese-operated copper mines) have had issues with worker safety and low wages. It remains critical that any expansion of cobalt production in Zambia or elsewhere avoids the pitfalls seen in the DRC supply chain.

Madagascar also contains major cobalt deposits (notably the Ambatovy nickel-cobalt mine). While Ambatovy is a joint venture of foreign firms (including Sumitomo and Sherritt), news reports have focused on its environmental impact rather than labor exploitation. As of late 2024, there are no prominent reports of child labor in Madagascar’s cobalt projects. Nevertheless, governance experts warn that any new cobalt rush could strain local oversight in economies with poverty-driven mining communities.

Comparatively, similar exploitation issues have arisen in other resource sectors and countries. For instance, the gold mining industry in West Africa (Ghana, Mali) has seen children pan for gold under hazardous conditions, often financed by foreign buyers (see [15†L70-L79] for analogous cases). Mining of cobalt’s cousin mineral coltan in the DRC has been controlled by rebel groups (e.g. M23) and smuggled through Rwanda, funding conflict.

In South America, reports have surfaced of lithium miners (e.g. in Argentina or Chile) facing poor labor conditions though large industrial operations make child labor less visible there. These parallels show a pattern: high global demand for “green tech” minerals can fuel abuses unless transparency and accountability are enforced internationally.

Legal and Policy Responses

Pressure is mounting on governments and regulators. In the U.S., lawmakers and the Department of Labor have formally recognized DRC cobalt as “produced by child labor” since 2009, but enforcement is limited. The U.S. is now considering legislation to restrict imports of goods tainted by such labor. In early 2024, Congress held hearings on how China’s dominance in Congo’s mining creates a forced-labor risk.

Internationally, the DRC government itself is taking action. In late 2024, Congo filed criminal complaints in Europe against Apple’s French and Belgian subsidiaries, accusing the tech giant of benefiting from “conflict minerals” (notably tin, tantalum and tungsten) from the region.

The complaints allege Apple used deceptive practices to hide the origin of minerals tied to Congo’s civil wars. Congo’s lawyers contend this is not just about 3T metals but part of a broader pattern of resource pillaging. Apple has denied wrongdoing, citing its auditing of smelters and a voluntary embargo on DRC minerals early in 2024.

At the same time, policy frameworks are emerging. In April 2024 the U.N. announced a panel of nearly 100 countries to draft voluntary guidelines for responsible mining of “critical minerals” (like cobalt) to curb human rights abuses.

These guidelines, while non-binding, signal growing international awareness. Industry initiatives from battery alliances to traceability certification are expanding, but NGOs caution that they often rely on companies policing themselves. As Umpula of Afrewatch warned, until supply chains are genuinely transparent, “the abuses in mines remain out of sight and out of mind“.

Regional efforts are underway too. In 2019 the DRC government created a national authority to oversee “strategic” minerals and even enforced a state monopoly (Gécamines) on some cobalt, aiming to formalize the sectori. However, enforcement remains weak.

On the continental scale, African Union negotiations are underway for a binding treaty on transnational corporations’ human rights impacts, which could eventually cover mining conglomerates. Civil society groups in Africa are also pressuring governments to renegotiate mining contracts and increase royalties, so local communities see more benefit.

Towards Accountability

In sum, this exposé reveals a stark injustice: the cobalt powering our phones and cars is dug from African ground by the world’s poorest, at tremendous human cos. Tech giants have profited immensely while contributing very little to improving working conditions. The evidence from victim testimonies to supply-chain analyses shows repeated patterns of neglect. Investigative journalist Siddharth Kara, who spent years on the ground, concluded that just publishing academic reports was insufficient; something must be done to “hold someone accountable” for the suffering.

The companies named have considerable means to act. According to plaintiffs’ lawyers, even a tiny fraction of tech profits could vastly improve miner safety or education in local communities. Some firms quietly fund NGOs and certification schemes, but critics say this is nowhere near what’s needed. Consumers, meanwhile, should realize the human rights implications of “green tech” consumption.

Until effective measures are in place from stricter import rules, to binding company liability, to genuine investments in alternative livelihoods, the cobalt sector’s abuses will likely continue.

This investigation calls for urgent reform: transparency in sourcing, unambiguous enforcement of child-labor bans, and legal accountability for corporations that benefit from exploitative mining. Only then can the tide turn on this unforgivable exploitation.

Citations And References

All citations in this investigation correspond to verified sources gathered during extensive research across multiple continents and databases. Full documentation available upon email to support the accuracy and verifiability of all claims made.

issafrica.org amnesty.org theguardian.com internationalrightsadvocates.org dol.gov.

About Our Investigative Services

Seeking to expose corruption, track illicit financial flows, or investigate complex criminal networks? Our specialized investigative journalism agency has proven expertise in following money trails, documenting human rights violations, and revealing the connections between organized crime and corporate malfeasance across the world and beyond.

Partner With Us for Impactful Change

Our investigative expertise and deep industry networks have exposed billion-dollar corruption schemes and influenced policy reform across Americas and beyond.

Whether you’re a government agency seeking independent analysis, a corporation requiring risk assessment and due diligence, or a development organization needing evidence-based research, our team delivers results that matter.

Join our exclusive network of premium subscribers for early access to groundbreaking investigations, or contribute your expertise through our paid contributor program that reaches decision-makers across the continent.

For organizations committed to transparency and reform, we also offer strategic partnership opportunities and targeted advertising placements that align with our mission.

Uncover unparalleled strategic insights by joining our paid contributor program, subscribing to one of our premium plans, advertising with us, or reaching out to discuss how our media relations and agency services can elevate your brand’s presence and impact in the marketplace.

Contact us today to explore how our investigative intelligence can advance your objectives and create lasting impact.

Read all investigative Stories on Technology.

* For full transparency, a list of all our sister news brands can be found here.