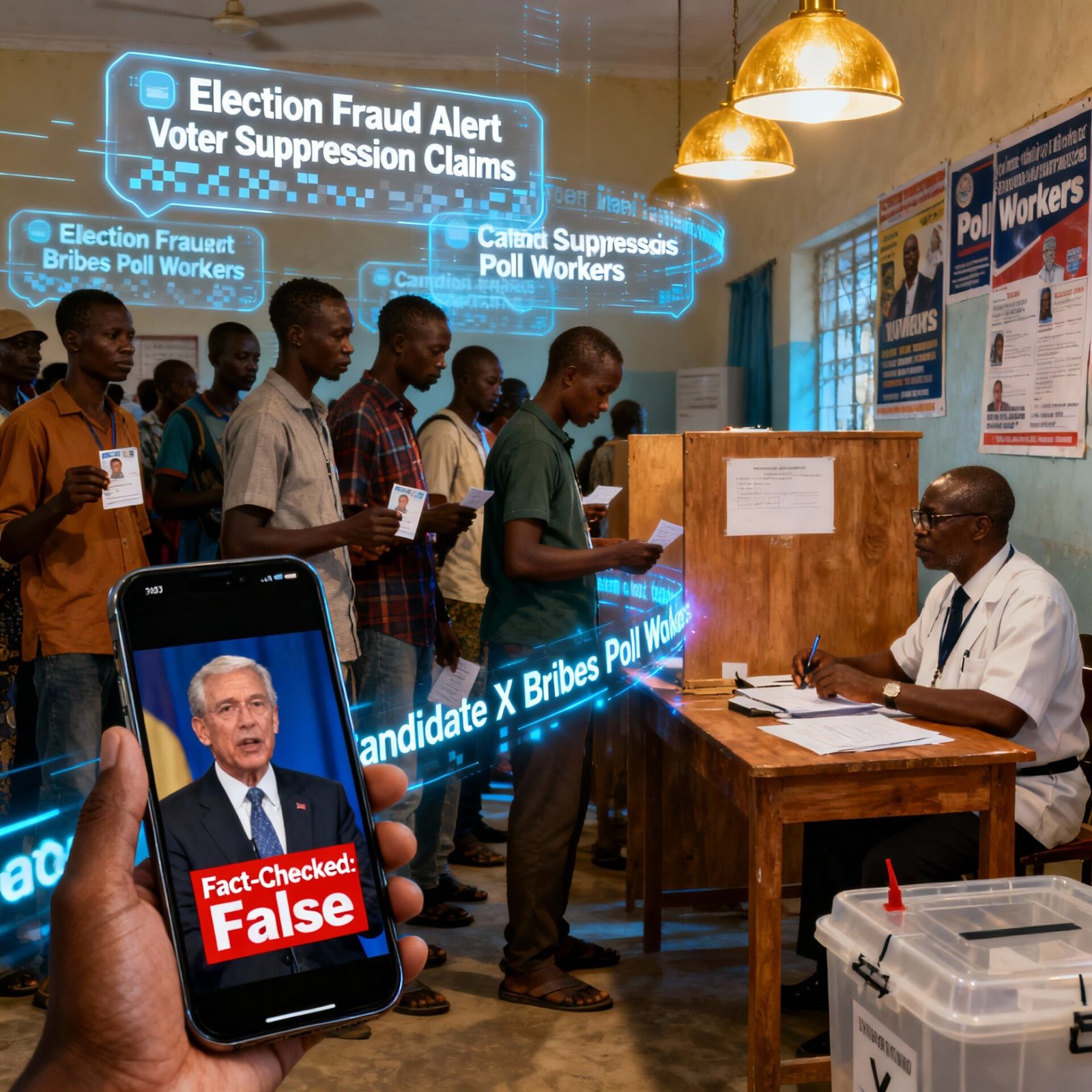

Foreign powers and private interests are intensifying campaigns of digital propaganda to influence African elections. In 2024, a record 80+ national votes involved half the global population. An Ipsos survey found 87% of people in 16 of these countries fear disinformation will skew results, with social media as the main source. The World Economic Forum warns that widespread misinformation “may undermine the legitimacy of newly elected governments,” fueling protests or worse. Foreign disinformation in African elections: An Investigative Report reveals dangerous propagandas by external global powers.

Even longstanding media actors are part of the problem: Iran, Russia, China, the UAE, Saudi Arabia and Qatar have all invested in covert propaganda networks targeting African electorates. In many cases state-run broadcasters, troll farms and local influencers are paid to spread narratives that favor foreign agendas or local strongmen.

According to an analysis by the Atlantic Council, 189 disinformation operations were documented in Africa in 2024 which is nearly four times the number in 2022. Regionally, Africa Center for Strategic Studies (ACSS) data shows deep foreign influence: Kremlin-affiliated networks appeared across much of North, Central, Southern and West Africa, often accompanied by China-linked campaigns in the south and west. Russia, China, the UAE, Saudi Arabia and Qatar together account for roughly 60% of those campaigns, with West Africa especially hard-hit.

Disinformation campaigns exploit Africa’s social media boom. Over 300 million Africans came online in the last seven years, and more than 400 million now use social platforms daily. In Kenya, Nigeria and other countries, many rely on a single shared device or local radio shows to consume this content – effectively making WhatsApp and Facebook a “radio” for the masses.

The result is a perfect storm: a digitally connected electorate hungry for news, facing an onslaught of fake endorsements and conspiracy memes. For example, ACSS notes that an Israeli-linked firm known as “Team Jorge” has pushed false narratives in over 20 African elections since 2015, using paid influencers to amplify divisive messages.

Content ranges from doctored videos to rumors of ballot-box theft circulated just before polls. In one Kenyan case, analysts found 130 TikTok videos of hate speech and lies posted over six months, racking up 4 million views. These platforms often lack enough moderators fluent in African languages, so false posts go unchecked (Mark Zuckerberg recently cut ties with African fact-checkers on Facebook). In sum, most African voters will make electoral decisions based on social media content – which increasingly comes freighted with foreign spin.

Foreign actors and their agendas

Investigations point to a wide cast of state and non-state players. Russia has perfected a “franchise” model: it quietly funds local operators to post Kremlin talking points and praise authoritarian allies on Facebook, X, WhatsApp and Telegram. Meta has dismantled several dozen networks pushing Russian ultranationalist content in at least eight African countries.

Likewise, China’s ruling party uses its vast media arm (CGTN, Xinhua, etc.) to seed narratives favorable to Beijing’s interests from praising Chinese-funded infrastructure deals to downplaying human rights abuses. The Gulf states and Turkey have also invested in influence operations: for example, the UAE targeted African journalists to slant coverage of Qatar’s 2022 World Cup.

Iran has reportedly spread propaganda in North and West Africa. On the Western side, past scandals expose even democratic governments meddling: the French military ran an online “troll farm” against rival Russian networks in the Central African Republic, and Britain’s Cambridge Analytica infamously interfered in Kenya and Nigeria’s votes.

These campaigns have clear goals – to reshape government policies and secure economic or strategic gains. By mixing half-truths with amplified critiques of Western governments, foreign influencers sow doubt about democracy itself. They lobby for mining and port deals, military bases, or support for coups. In Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso, Facebook-based disinformation helped drum up backing for recent military takeovers.

In Sudan, the Rapid Support Forces used social media to promote a false image of popular support after overthrowing their own government. Meanwhile, ACSS analysts warn, “foreign state actors are heavily invested in influencing the African political space”, treating disinformation as a cheap yet potent tool of geopolitical competition.

How disinformation spreads online

Digital sleuths describe these campaigns as highly orchestrated. Local influencers are paid to impersonate real voters. Fake news sites mimic respected outlets. For instance, Ghanaian fact-checker Gifty Tracy Aminu reports that ahead of elections, propagandists create phony media pages (matching the logos and colors of legitimate broadcasters) to publish bogus election-day videos and claims.

Before Ghana’s December vote, she saw syndicates repost old footage of unrest and falsely claim polling stations were attacked just hours before polls opened. Advanced tactics are now common: the 2023 Nigerian presidential race was flooded with AI-generated clips and celebrity endorsements to mislead voters, and deepfaked speeches from foreign leaders have circulated in South Africa’s 2024 campaigns. AI tools can cheaply produce convincing disinformation, making the threat even harder to track.

The results are dangerous

Disinformation erodes trust and can inflame violence. In Kenya, a protracted political crisis (2007–08) left over 1,300 dead; experts worry that current online lies could ignite similar clashes. A Reuters survey found 75% of Kenyans struggle to distinguish real news from fakes, and 60% had seen political falsehoods in just one week.

Amnesty International Kenya’s executive director Irungu Houghton warns: “Online disinformation, where truth is deliberately distorted to drive particular agendas during elections, is extremely dangerous, and it’s very difficult to stop once it’s out there.”. Kenyan officials note that most hate speech online is “organised,” with dozens of accounts used to spread lies. The National Cohesion and Integration Commission has opened cases against individuals for incitement on social media.

In other countries, similar patterns emerge: violent rumors circulated over WhatsApp in Kenya and Nigeria, while after Burkina Faso’s 2022 coup, fake videos of foreign commentators endorsing the regime went viral in local feeds. Each campaign targets citizens directly, often at night or during commutes on village phones, to muddy election results and polarize communities.

Comparative insights worldwide

Africa’s experience mirrors a global disinformation trend. Western democracies have long confronted similar tactics. U.S. intelligence established that Russian troll farms interfered in the 2016 and 2020 U.S. elections via social media manipulation, and European countries have reported Kremlin disinfo in referenda and votes. By the same token, private “influence firms” have operated internationally for example, Cambridge Analytica (UK) ran covert campaigns across Africa, Latin America and even U.S. elections.

China’s influence operations extend beyond Africa into Southeast Asia and Oceania. In Brazil’s 2018 vote, WhatsApp groups were used to spread fake news to tens of millions of citizens. Like in Africa, these cases show a basic pattern: hostile or profit-seeking actors exploit digital media in any democracy, native or abroad, to shape the outcome. What differs is language and context.

In sub-Saharan Africa, low internet penetration (60% of people) and fewer fact-checkers make populations especially vulnerable. But the playbook of fake pages, bots, viral memes is the same. Researchers warn that emerging AI tools will deepen this global problem: social media giants are racing to add context labels and funding local fact-checks, but these measures alone cannot match the pace of new propaganda.

Voices from the field

Across Africa, journalists, civil society and ordinary voters report the same frustration. “The mainstream media is also involved in disinformation to serve their own interest, as most are aligned with a certain ideology,” says Ghanaian fact-checker Aminu, noting how state-linked stations sometimes produce misleading pieces. In Nigeria, an election observer noted that many older citizens were confused by WhatsApp forwards, believing sensational videos of rigged elections.

In Senegal, a digital rights activist cautioned that foreign narratives blaming the West for Africa’s problems “play well with youth who feel left out,” even as he teaches media literacy in schools. South African pollsters express concern that tribalist rumors amplified online could again be the tipping point in an already contested vote.

In sum, those most impacted are everyday Africans like farmers, students and the urban youth who rely on mobile newsfeeds and radios. They find it hard to get clear signals amidst the noise: surveys show that over 80% across multiple countries have seen political rumors on social media. Several interviewed legal experts warn that many national laws have not kept up; unless parliaments impose transparency rules on political ads and foreign funding, these shadow campaigns will continue unchecked.

Efforts to combat the tide of Foreign disinformation in African elections

The scale of disinformation has prompted responses. Grassroots fact-checkers like Ghana’s PesaCheck, Nigeria’s Dubawa and South Africa’s Africa Check now validate thousands of viral posts each year. Journalists are collaborating with international tech coalitions to train in election reporting. Governments and regional bodies are drafting media integrity laws and threat-monitoring teams. International partners like the African Union and ECOWAS held workshops on electoral cyberthreats.

Meta has begun labeling content and partnering with local fact-checkers in Nigeria and Kenya (though it recently cut ties with some checkers, drawing criticism). Civil society groups run voter awareness campaigns on WhatsApp to identify common hoaxes. But experts say these steps lag behind the problem’s speed. As Reuters Foundation reports on Kenya, “platforms are awash with slick graphics, pictures and videos promoting false and misleading information” with little pushback.

Content can linger online for hours or days before takedowns, and when it appears in non-English languages, moderators often fail to catch it. In this information war, legal and technical fixes will take time. Meanwhile, analysts stress that building public resilience through education and trusted media is vital. Indeed, surveys by Afrobarometer confirm that most Africans still prefer democracy and reject dictatorship, suggesting a foundation of goodwill if truth can be preserved.

Conclusion

The evidence is clear: foreign disinformation campaigns pose a serious threat to free and fair elections across Africa. States and societies cannot ignore the mounting danger. Politicians and civic leaders must publicly denounce these outside influences and enact laws requiring transparency of online political ads and foreign funding. Social media companies must dramatically improve moderation in African languages and reroute resources to local fact-checking. Voter education initiatives are urgent: citizens need tools to spot doctored videos and false posts. As the ACSS study asserts, protecting the integrity of elections “is paramount” for the continent’s stability.

To strengthen defenses, we call on top decision-makers and campaign organizers to partner with our agency. We specialize in researching and countering digital influence operations. Engage us for bespoke consulting, detailed media monitoring, or join our paid subscription service for regular intelligence briefs. You can also support independent journalism: advertise with our network of investigative reporters or apply to become a contributor. Together, we can build a bulwark against propaganda and safeguard African democracy.

Citations And References

All citations in this investigation correspond to verified sources gathered during extensive research across multiple continents and databases. Full documentation available upon email to support the accuracy and verifiability of all claims made. wits.ac.za civictech.africa reuters.com democracyinafrica.org.

About Our Investigative Services

Seeking to expose corruption, track illicit financial flows, or investigate complex criminal networks? Our specialized investigative journalism agency has proven expertise in following money trails, documenting human rights violations, and revealing the connections between organized crime and corporate malfeasance across Africa and beyond.

Partner With Us for Impactful Change

Ready to drive transparency and accountability in your sector?

Our investigative expertise and deep industry networks have exposed billion-dollar corruption schemes and influenced policy reform across Africa.

Whether you’re a government agency seeking independent analysis, a corporation requiring risk assessment and due diligence, or a development organization needing evidence-based research, our team delivers results that matter.

Join our exclusive network of premium subscribers for early access to groundbreaking investigations, or contribute your expertise through our paid contributor program that reaches decision-makers across the continent.

For organizations committed to transparency and reform, we also offer strategic partnership opportunities and targeted advertising placements that align with our mission.

Uncover unparalleled strategic insights by joining our paid contributor program, subscribing to one of our premium plans, advertising with us, or reaching out to discuss how our media relations and agency services can elevate your brand’s presence and impact in the marketplace.

Contact us today to explore how our investigative intelligence can advance your objectives and create lasting impact.