Chile’s economy is built on copper. The Andean nation has become one of the world’s leading suppliers of copper, lithium and other minerals, and the profits have created some of the wealthiest families in Latin America. This investigative report explores how that wealth has been deployed to influence politics via mining magnates in chilean campaign financing.

Over more than a decade, Chilean mining magnates and related conglomerates have funnelled millions of pesos into election campaigns. They have used both legal and illicit methods: legal “reserved contributions” that hide the donor’s identity, opaque networks of subsidiaries that circumvent donation caps, and fake invoices that channel corporate money to politicians.

The result is a democratic system where industrial fortunes exert silent pressure on policy and where corruption scandals have rocked public trust.

In the following investigative report, we document the scope and mechanisms of this financing, scrutinise the personalities involved, examine legal reforms and their limits, and compare Chile’s experience with other countries where the mineral wealth has seeped into politics.

Methodology used to investigate Mining Magnates In Chilean Campaign Financing

This report synthesises public records, court documents, academic studies, and investigative journalism from trusted Chilean outlets such as CIPER Chile, La Tercera and El Mostrador. It draws on the testimony of individuals involved in the scandals, statements from business leaders, and the recommendations of the 2015 Engel Commission.

To provide comparative context, the report includes evidence from other countries: court proceedings related to the Brazilian conglomerate Odebrecht’s financing of Peruvian campaigns; reports on the role of Australian mining magnates Gina Rinehart and Clive Palmer in political funding; and U.S. Federal Election Commission filings showing oil and gas executives’ donations to Donald Trump’s presidential campaigns. All facts and figures are tied to verifiable sources, with citations presented at the end.

The Historical Context: Mining, Wealth and Politics in Chile

Chile’s modern history cannot be understood without its mineral wealth. The nationalisation of copper in 1971 and its subsequent partial reprivatisation under military rule created a class of entrepreneurs who benefitted from privatised state enterprises.

These families built conglomerates with interests spanning banking, forestry, retail and mining. By the early 2000s, the Luksic, Angelini, Matte and Ponce Lerou families were among the richest in the hemisphere. Their influence extended beyond boardrooms into the halls of Congress, as corporate donations became a central feature of political campaigns.

Legal Foundations of Campaign Financing

Chile’s first modern campaign finance law (Law 19.884 of 2003) allowed private funding through direct donations, tax-deductible contributions and anonymous “reserved contributions.” The system mixed private and public funding but lacked robust enforcement and transparency. Companies could deduct donations from taxes, and the lack of disclosure meant that citizens seldom knew who was funding their representatives. Only after successive scandals would significant reforms be introduced.

The Penta and SQM Scandals: Catalysts for Reform

Penta: An Insurance Empire’s Political Machine

Grupo Penta, a financial holding company led by Carlos Alberto Délano and Carlos Eugenio Lavín, became notorious in 2014 when prosecutors uncovered a scheme of issuing fake invoices to funnel corporate money to politicians. The Penta case implicated high-profile business figures and politicians, particularly from the right-wing Independent Democratic Union (UDI).

Reuters reported that prosecutors accused Penta’s owners of creating false invoices to make illegal campaign contributions. The scandal reached as far as a junior mining minister in the administration of then‑President Sebastián Piñera. The case exposed how corporate donations had become entangled with tax fraud and bribery.

SQM: A Mining Giant’s Network

Sociedad Química y Minera de Chile (SQM), controlled by Julio Ponce Lerou, Augusto Pinochet’s former son-in-law was at the centre of the most far-reaching campaign finance scandal. Prosecutors found that SQM issued fake invoices to pay politicians across the political spectrum.

The network involved politicians from right-wing parties RN and UDI as well as members of the centre-left Nueva Mayoría coalition. In 2017 the company agreed to a $15 million fine with the U.S. Department of Justice for violating the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. The “Penta-SQM” affair triggered a national debate about the corrosive effects of corporate money in politics and prompted the creation of the Engel Commission.

Testimony from the Inner Workings

Investigations revealed that SQM used a web of 24 companies to issue more than 2.2 billion pesos in fake invoices. Some of these companies were linked to ex‑President Piñera’s family through his family office Bancorp and his media company Vox Populi. Another group of companies belonged to Ponce Lerou’s trusted advisor Roberto Guzmán Lyon; these entities, such as Inversiones Enjoy and Dasco Tecnologías, issued dozens of invoices without providing any real services.

Employees were asked to generate invoices for non-existent work, deposit the payments into personal accounts, and then return the money to political intermediaries. One witness, Solange Hermosilla, testified that she was instructed by Carmen Luz “Titi” Valdivielso to bill SQM and then hand back the money for use by Fundación Chile Justo, a think‑tank connected to UDI politician Pablo Longueira. She also recalled being asked to invoice fishing companies like Pesquera El Golfo, linking the mining scandal to the fishing sector.

The Role of Think‑tanks and Foundations

SQM and other donors used think‑tanks and foundations to disguise political spending. CIPER Chile uncovered how Longueira’s Fundación Chile Justo, ostensibly established to fight social inequality, functioned as a conduit for campaign money. The organisation won municipal contracts to produce jingles and videos and subcontracted these tasks to another foundation, Chile Cultura.

Another entity, Centro de Estudios Nueva Minería, presented itself as a policy think‑tank and charged membership fees to mining companies like Anglo American, Collahuasi and SQM. According to an executive at one of these firms, the services provided were generic and did not justify the fees. Hermosilla testified that she was asked to issue invoices to this centre as part of the same network.

The Business Groups: How Mining Magnates Fund Politics

While the Penta-SQM scandal exposed illegal practices, it also drew attention to the legal mechanisms available for wealthy industrialists to support politicians. Chile’s campaign finance law allowed companies to make tax-deductible contributions up to 10,000 Unidades de Fomento (UF) per election, about 247 million pesos.

However, conglomerates could bypass these caps by splitting donations across multiple subsidiaries, a practice called “multi-RUT” or by using anonymous reserved contributions. CIPER obtained board minutes and sustainability reports that detail how the country’s biggest business groups allocated money to campaigns.

The Luksic Family: Copper and Credit Lines

The Luksic family controls Antofagasta PLC, a major copper miner, along with a diversified conglomerate encompassing banking (Banco de Chile), beverages (CCU) and shipping (CSAV). With a fortune exceeding US$13 billion, the family has long been among Chile’s largest political donors.

A CIPER report listed 18 companies from the Luksic group that made campaign contributions between 2005 and 2013. These included the copper mine Minera Los Pelambres, Antofagasta Minerals’ other operations (Esperanza, El Tesoro) and beverage companies like CCU.

In July 2013 the board of Minera Los Pelambres approved a donation of up to 36,000 UF—equivalent to approximately 825 million pesos (about US$1.6 million)—for election campaigns. The minutes show that the directors argued for “equity” among political candidates but provided no details on how the money would be distributed.

The board of the group’s beverage subsidiary CCU also authorised donations in 2009, using reserved contributions to keep recipients confidential. Hernán Büchi, a former finance minister and key advisor to the Luksics, attended board meetings and reportedly influenced decisions on political giving. Despite repeated donations, the group insisted that contributions were made to promote transparency and did not seek legislative favors.

The Matte Group: Paper and Power

The Matte family is known for its control of CMPC (a forestry and paper giant), the power company Colbún, Banco Bice and other holdings. CIPER found that the group topped the list of corporate donors with 33 companies giving to political campaigns. In a 2013 sustainability report, CMPC listed campaign contributions totaling US$1.345 million (823 million pesos) and disclosed donations dating back to 2004 that exceeded US$3.7 million.

The group used both legal reserved contributions and subsidiaries to bypass the 10,000 UF cap. When the scandal broke, patriarch Eliodoro Matte admitted that the family had financed candidates through reserved contributions but maintained that he never pressured lawmakers: “Hemos financiado a candidatos a través de aportes reservados… Yo jamás he llamado a un parlamentario para pedirle que vote en tal o cual sentido”.

The Angelini Group: Fishing and Forestry Ties

The Angelini family, one of South America’s wealthiest dynasties, controls companies across forestry (Arauco), fishing (Corpesca, Orizon), energy and fuel distribution. CIPER reported that Corpesca’s board decided to provide political donations in the 2013 election cycle and justified the giving as a “responsibility” to support democracy.

However, evidence later emerged that Corpesca had paid 25 million pesos to an adviser of deputy Marta Isasi in exchange for support of a new fishing law. The Council for the Defense of the State filed bribery and corruption charges against Isasi, her adviser, and the manager of Corpesca. This case illustrated how legal contributions could be intertwined with illegal lobbying and legislative capture.

Julio Ponce Lerou: The Caserón de las Cascadas

Julio Ponce Lerou, former chairman of SQM and ex–son‑in‑law of dictator Augusto Pinochet, has long been a controversial figure in Chilean business. Beyond the SQM scandal, Ponce Lerou was involved in the 2014 “Cascadas” case, in which the securities regulator accused him of manipulating share prices among a cascade of interlinked companies.

In the campaign financing zone, CIPER documented how his inner circle used companies like Inversiones Enjoy and Dasco Tecnologías to issue dozens of invoices to SQM for non-existent services. Ponce Lerou denied knowledge of illegal contributions but acknowledged that SQM had made reserved contributions of more than US$1 million in the last presidential and parliamentary campaign.

The Von Appen and Bethia Groups: Silent Supporters

Other conglomerates joined the fray. The Von Appen family, owners of the shipping company Ultranav, used at least 13 companies to donate to campaigns. Their head, Wolf von Appen, also served on SQM’s board, illustrating the overlapping networks among Chile’s elite.

The Bethia group, led by the Heller Solari family, controlled Falabella and other retail giants; they matched the Luksics in the number of donating companies, with subsidiaries like Falabella Retail and Sodimac providing millions of pesos. Like the Luksics and Mattes, these groups insisted that contributions were made legally and without expectations, yet the scale of their giving raised concerns about undue influence.

Mechanisms of Influence: Legal Loopholes and Illicit Schemes

Reserved Contributions and the Multi‑RUT Strategy

Before the 2016 reforms, Chile’s campaign finance law permitted companies to donate anonymously through “aportaciones reservadas.” While the amounts were reported to the election service (Servel), the identities of donors remained secret. Wealthy families exploited this mechanism to support candidates across the spectrum, often preferring those likely to protect their interests.

They also used multiple subsidiaries (each with its own tax identification number) to circumvent the 10,000 UF cap, a practice CIPER dubbed “multi‑RUT.” For example, Endesa Chile and its parent Enersis donated US$3.5 million combined during one election cycle, splitting the sum among various subsidiaries. This allowed them to far exceed the nominal limit while still staying within the law.

Fake Invoices and Tax Fraud

The Penta and SQM cases revealed a more sinister mechanism: companies issued fake invoices for non-existent services, paid the invoicing individuals, and then channelled the money to political intermediaries. Employees were compensated for the risk or coerced through job security. Some used their personal tax accounts to invoice large sums and then returned the funds in cash.

The scheme allowed companies to deduct campaign contributions as business expenses, thus defrauding tax authorities. In the case of Penta, prosecutors charged its owners with bribery and tax evasion. Similarly, SQM’s network of 24 companies generated more than 2.2 billion pesos in bogus invoices, implicating individuals from across the political spectrum.

Think‑tanks, Foundations and Consultancy Contracts

Beyond direct giving, corporations financed politicians through ostensibly independent foundations and think‑tanks. Fundación Chile Justo and Centro de Estudios Nueva Minería offered consulting services and charged membership fees to firms like Anglo American, Collahuasi and SQM. Investigators found little evidence of substantive work produced.

In some cases, the same foundation would subcontract a sister organisation to produce campaign materials such as jingles, enabling donors to claim they were funding community projects rather than political propaganda. These methods blurred the line between philanthropy and campaign spending.

The Legal Reforms: Law 20.900 and the Engel Commission

Engel Commission Recommendations

In January 2015, after the Penta-SQM scandal erupted, President Michelle Bachelet convened the Consejo Asesor Presidencial contra los Conflictos de Interés, el Tráfico de Influencias y la Corrupción, popularly known as the Engel Commission. Its final report observed that the existing mixed financing system left parties dependent on private money for their day‑to‑day operations, creating a risk of policy capture.

The commission recommended a comprehensive overhaul: banning corporate donations, increasing public funding, reducing spending limits, and strengthening enforcement. It emphasised the need for transparency, internal democracy in parties, and strong sanctions against violators.

Law 20.900: Strengthening and Transparency of Democracy

The Chilean Congress responded by passing Law 20.900, promulgated in April 2016. According to Servel’s official summary, the law introduced several key changes: it increased public funding to parties (0.02 UF per vote and 0.04 UF reimbursement), permanently financed parties with quarterly contributions, and prohibited donations from legal entities (companies) altogether.

It reduced campaign spending limits by 50%, capped individual contributions at 10% of the spending ceiling, and required all contributions above 40 UF (about US$1,500) to be public, effectively ending anonymous reserved contributions. The law also limited candidates’ self-funding to 25% of total spending, mandated disclosure of bank accounts for campaign transactions, and introduced sanctions ranging from fines to loss of office and even imprisonment for serious violations. These reforms marked the most significant overhaul of political financing since the restoration of democracy.

Impact and Remaining Gaps

While Law 20.900 closed several loopholes, critics argue that it has not fully addressed the issue of undue influence. Public funding remains relatively modest compared to campaign costs, and parties continue to seek private support through informal channels. The law does not regulate third‑party political advertising or digital campaigns, leaving a gap exploited by interest groups and online advertising firms.

Enforcement is also limited by the capacities of Servel and the judiciary, and cases can take years to resolve. Nonetheless, the prohibition of corporate donations has curtailed the explicit role of mining companies, pushing them toward more subtle forms of influence, such as lobbying and philanthropic projects in mining regions.

Consequences: Policy Capture and Public Disillusionment

Influence on Legislation

The flow of mining money into campaigns has had concrete policy ramifications. During debates over the Fishing Law in 2012, companies like Corpesca lobbied fiercely, paying advisers and donating to politicians. The resulting law granted long-term quotas to industrial fisheries, benefiting large firms over artisanal fishers.

Corpesca’s payment of 25 million pesos to deputy Marta Isasi’s adviser, which prosecutors allege was a bribe, illustrates how donations could be tied to specific legislative outcomes. Similarly, the energy conglomerates’ donations coincided with the approval of mega-projects like HidroAysén, a controversial dam project that ultimately failed due to environmental opposition but highlighted the power of corporate lobbying.

Erosion of Public Trust

The Penta and SQM scandals severely damaged citizens’ trust in institutions. Polls showed a sharp decline in confidence in parties and Congress during 2014‑2016. Street protests demanded accountability, while activists denounced the “capture” of the state by economic elites.

The revelations that companies across the ideological spectrum like energy firms, banks, forestry companies, retail chains had funded campaigns through secret contributions fed a narrative that democracy served corporate interests. Even after Law 20.900, suspicion persists about hidden flows of money. Transparency advocates argue that long-standing ties between politicians and business leaders continue to shape policy behind closed doors.

Effects on Competition and Representation

Another consequence is the distortion of electoral competition. Candidates linked to wealthy donors enjoy financial advantages in advertising, travel and staffing. This creates barriers for new actors, including independent candidates, grassroots movements and smaller parties. The cumulative effect is a political landscape where the same families and networks recycle power, reinforcing socioeconomic inequality. The use of subsidies via subsidiaries also means that larger conglomerates can outspend local entrepreneurs, weakening pluralism.

Voices from the Field: Interviews and Testimonies

Corporate Perspectives

When CIPER confronted members of the elite about campaign donations, many insisted they were exercising a civic duty. Eliodoro Matte, patriarch of the Matte family, admitted to financing candidates through reserved contributions but denied exerting political pressure. “I have never called a member of parliament to ask him to vote in such or such a way,” he told reporter. Directors at Endesa and Enersis emphasised that donations were meant to “promote transparency” and support democracy. On the record, board minutes of Los Pelambres show directors arguing for equality among candidates when approving an 825 million peso donation.

Testimony of Intermediaries

The Penta-SQM investigation uncovered personal accounts of middlemen and employees who participated in the schemes. Solange Hermosilla, a former assistant to UDI politician Pablo Longueira, testified that she was instructed to issue invoices for services never rendered and return the money to Valdivielso for the Foundation Chile Justo.

She described a pattern where she also invoiced fishing companies and the think‑tank Centro de Estudios Nueva Minería. Another employee told investigators that the think‑tank charged membership fees to mining companies for generic documents and minimal services. Their testimonies reveal the human cost of systemic corruption: low-level workers were used as conduits while the masterminds remained insulated.

Legal Experts and Scholars

Legal scholars emphasise that Chile’s experience is not unique but part of a broader trend in which economic elites capture regulatory processes. The Engel Commission’s experts argued that only robust public funding could reduce dependency on private donors and recommended strong sanctions for violations.

Political scientist Claudio Fuentes noted that the 2016 reforms have improved transparency but have not eliminated the influence of big business, which now manifests through lobbying and think‑tanks rather than direct donations. Constitutional law professor Miriam Henríquez warned that without better enforcement and public oversight, new forms of “legal corruption” would emerge, such as disguised consulting contracts and digital propaganda financed by corporations.

Comparative Insights: Mining Money and Politics Beyond Chile

Peru: Odebrecht and Political Capture

Chile’s neighbours have faced similar scandals. In Peru, the Brazilian construction and mining conglomerate Odebrecht admitted to financing electoral campaigns across the region. During a Peruvian court proceeding, Marcelo Odebrecht testified that his company contributed US$3 million to the 2011 presidential campaign of Ollanta Humala.

Another executive revealed that the company donated US$1.5 million to Mauricio Funes in El Salvadorapnews.com. These payments were often bundled with promises of public works contracts. The resulting Lava Jato investigations implicated several Peruvian presidents and business leaders, showing that corporate capture of campaigns is a regional issue.

Australia: Gina Rinehart and Clive Palmer

In Australia, mining billionaire Gina Rinehart has become a prominent fundraiser for the conservative Liberal National Coalition. In March 2025 she hosted an exclusive dinner that raised more than AU$385,000; guests paid between AU$10,000 and AU$25,000 to attend.

Her company Hancock Prospecting donated AU$325,000 to the Liberal National Party of Queensland, AU$75,000 to the Country Liberal Party in the Northern Territory, and AU$100,000 to the Liberal Party of South Australia in the 2023‑24 financial years. While these donations are legal under Australian law, transparency advocates caution that they give resource companies privileged access to policymakers.

Another Australian mining magnate, Clive Palmer, has used his fortune to bankroll his own political party. Financial disclosures show that his company Mineralogy contributed AU$7.088 million to the United Australia Party in 2022‑23. This spending occurred during record-high election expenditures and prompted calls for real-time donation disclosures and tighter caps. Australia’s system allows high individual contributions, and critics say it fosters a political marketplace where wealthy individuals can buy influence.

United States: Fossil Fuel Money in Presidential Campaigns

The United States offers another instructive case. During the 2024 U.S. presidential campaign, former President Donald Trump received US$14.1 million from the oil and gas industry by August 31, making it his fourth-largest source of funding.

Major donors included Kelcy Warren of Energy Transfer (nearly US$6 million), Timothy Dunn of CrownQuest (US$5 million) and Harold Hamm of Continental Resources (US$1.2 million). Additional contributions followed after Trump asked industry executives for US$1 billion in exchange for deregulatory promises. While the U.S. Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision permits unlimited corporate spending via super PACs, the scale of industry donations highlights how resource companies invest in political outcomes.

Infographics and Data Visualisations

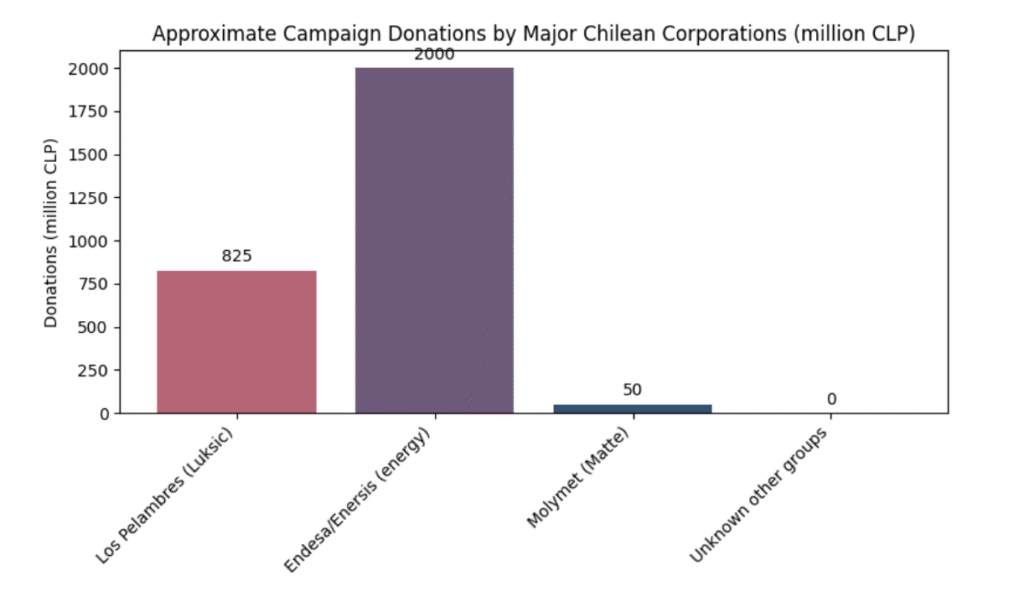

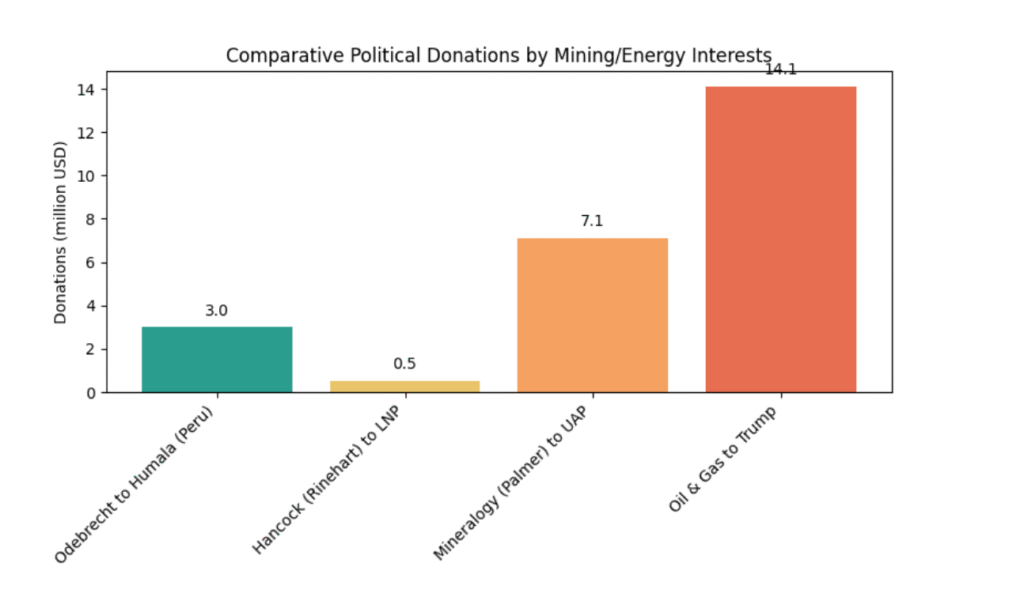

To illustrate the financial flows, we created two comparative charts. The first shows the approximate sums donated by major Chilean corporations during pre‑reform election cycles. Because the exact amounts of reserved contributions remain secret, the chart includes only cases where board minutes or sustainability reports disclosed numbers. The second chart compares large political donations in Chile with those from mining magnates in Peru, Australia and the United States.

Chilean Corporate Donations

The chart above uses figures from CIPER reports: Minera Los Pelambres (Luksic group) approved up to 825 million pesos (36,000 UF) for one election; Endesa and Enersis together donated roughly 2 billion pesos (about US$3.5 million) by splitting contributions across subsidiaries; Molymet (partly owned by the Matte family) approved 50 million pesos. “Unknown other groups” represents donors whose amounts remain undisclosed due to reserved contributions. The disparity illustrates how energy firms and mining subsidiaries could outspend other sectors. It also shows why reforms sought to cap donations and ban corporate giving.

International Comparison

This comparative chart converts donations to U.S. dollars for clarity. Odebrecht’s US$3 million contribution to Ollanta Humala’s campaign appears modest next to the US$7 million that Clive Palmer’s Mineralogy poured into his United Australia Party and the US$14.1 million that oil and gas executives contributed to Donald Trump.

Gina Rinehart’s donations to Australian parties total roughly US$500,000, while smaller and aggregated contributions by her dinner guests add to the sum. These comparisons show that the phenomenon of resource magnates influencing politics is global and that the scale varies with legal frameworks and personal fortunes.

Analysing International Parallels

Similarities Across Borders

Three common patterns emerge from the comparative cases:

Concentration of Wealth and Influence: In Chile, a handful of families control most mineral wealth. In Australia, Gina Rinehart and Clive Palmer wield outsized political influence because of their fortunes. In the U.S., a few oil and gas executives contribute the bulk of industry donations. When wealth is concentrated, corporate political donations amplify existing inequalities.

Legal Loopholes and Oversight Gaps: Chile’s pre‑2016 law allowed anonymous corporate contributions and multi‑RUT strategies. Australia permits large individual donations and does not require real-time disclosure. The U.S. allows unlimited spending via super PACs. In Peru, weak enforcement allowed Odebrecht to finance multiple campaigns. Each country faces a gap between legal norms and enforcement capacity.

Link Between Donations and Policy: All cases show a relationship between contributions and favourable policy. In Chile, donations coincided with the passage of the Fishing Law and support for mega-projects. In Australia, donors gained access to ministers at exclusive dinners. In the U.S., donors secured promises to roll back environmental regulations. In Peru, Odebrecht won lucrative contracts after financing campaigns.

Differences and Cultural Context

Legal frameworks and public perceptions vary. Chile’s reforms banned corporate donations, reflecting a strong backlash after the Penta-SQM scandal. Peru’s Lava Jato investigations led to criminal prosecutions but left campaign finance rules largely unchanged. Australia and the U.S. treat political donations as free speech; while there are disclosure requirements, caps remain high, and corporations can finance parties indirectly. Cultural attitudes toward corruption also differ. Chilean society responded with mass protests and demands for transparency, whereas in the U.S. corporate donations are largely accepted as part of politics.

Lessons and Recommendations

Strengthening Public Financing

The Chilean experience underscores the need for robust public financing. Private money enters politics because campaigns are expensive and parties lack resources. The Engel Commission recommended increasing public funding and conditioning it on internal democracy. Law 20.900 made strides by providing quarterly funding and reimbursing votes, but parties report that the amounts are insufficient. To minimise private influence, public funding should cover the full cost of modest campaigns, and its distribution should be equitable to encourage competition.

Enforcement and Transparency

Even the best laws require enforcement. Chile’s Servel and the public prosecutor’s office need greater resources to audit campaign accounts, investigate suspicious transactions, and prosecute offenders. Technology can enhance transparency: mandatory real-time publication of donations and expenditures, accessible databases, and open data formats. Civil society and media play a crucial watchdog role, as CIPER’s investigations demonstrate. Strengthening whistleblower protections would encourage insiders like Hermosilla to come forward without fear of reprisal.

Regulating Third Parties and Digital Campaigns

The next frontier is the regulation of third-party organisations, think‑tanks and digital advertising. Chile’s reforms left a loophole whereby foundations and consultancies can finance campaigns indirectly. Rules should require any organisation spending money on electoral messaging to register and disclose donors. Digital platforms need to provide public archives of political ads and the identities of their buyers. Without such measures, corporate interests can shift their spending online and continue influencing voters covertly.

Comparative Reflection and Regional Cooperation

Chile can learn from and contribute to regional efforts against corruption. Coordinated initiatives with neighbouring countries could harmonise campaign finance rules, share investigative information and prevent cross-border laundering of political funds. Latin American democracies share similar challenges with economic elites capturing politics; joint actions could strengthen collective bargaining power against corporate influence. Global conventions, such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Anti-Bribery Convention and the United Nations Convention against Corruption, provide frameworks for cross-border cooperation.

Conclusion

Over the past decade, Chile has confronted a painful truth: its democracy has been financially dependent on its mining magnates. The Penta and SQM scandals exposed how wealthy families like the Luksics, Matte, Angelini and Ponce Lerou financed politicians through legal loopholes and illegal schemes.

Investigations revealed networks of fake invoices, foundations masquerading as social projects, and board meetings where millions of pesos were quietly allocated to campaigns. The public outcry prompted significant reforms, culminating in the 2016 law that banned corporate donations and increased transparency. Yet the influence of wealth persists. Mining magnates continue to shape politics through lobbying, philanthropic ventures and think‑tanks, while enforcement agencies struggle to keep pace.

Comparative cases from Peru, Australia and the United States show that the interplay between natural resource wealth and political finance is global. Whether through Brazilian construction firms buying influence in Peru, Australian billionaires underwriting parties or U.S. oil tycoons funding presidential campaigns, the pattern is consistent: concentrated wealth seeks political returns.

Chile’s reforms represent a meaningful step, but lasting change requires vigilance, robust public funding, and a cultural shift toward transparency. Democracy cannot thrive if policy is sold to the highest bidder. As citizens demand accountability and new laws restrict corporate money, the challenge is to close remaining loopholes and ensure that public office is earned through ideas and service, not through the largesse of mining magnates.

Citations And References

All citations in this investigation correspond to verified sources gathered during extensive research across multiple continents and databases. Full documentation available upon email to support the accuracy and verifiability of all claims made.

About Our Investigative Services

Seeking to expose corruption, track illicit financial flows, or investigate complex criminal networks? Our specialized investigative journalism agency has proven expertise in following money trails, documenting human rights violations, and revealing the connections between organized crime and corporate malfeasance across Africa and beyond.

Partner With Us for Impactful Change

Ready to drive transparency and accountability in your sector?

Our investigative expertise and deep industry networks have exposed billion-dollar corruption schemes and influenced policy reform across Americas.

Whether you’re a government agency seeking independent analysis, a corporation requiring risk assessment and due diligence, or a development organization needing evidence-based research, our team delivers results that matter.

Join our exclusive network of premium subscribers for early access to groundbreaking investigations, or contribute your expertise through our paid contributor program that reaches decision-makers across the continent.

For organizations committed to transparency and reform, we also offer strategic partnership opportunities and targeted advertising placements that align with our mission.

Uncover unparalleled strategic insights by joining our paid contributor program, subscribing to one of our premium plans, advertising with us, or reaching out to discuss how our media relations and agency services can elevate your brand’s presence and impact in the marketplace.

Contact us today to explore how our investigative intelligence can advance your objectives and create lasting impact.

Read all investigative stories About Americas.

For Transparency, a list of all our sister news brands can be seen here.