Since Pakistan’s founding and partition from India in 1947, political life especially in the provinces has been dominated by a handful of powerful families and political dynasties in Pakistani Provinces. Punjab, Sindh, Balochistan, and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa each have entrenched clans who alternately ally and compete for power. Critics argue that this family-based politics has stymied real democracy. One researcher notes that in Pakistan “electoral politics is a family business,” with “few families ruling the legislatures” like an oligarchy.

Indeed, a detailed study by Pakistan’s Development Research shows that in recent elections over half of lawmakers are from dynasties. These dynasts often underperform in office: constituencies electing non-dynasts tend to see better development and services (water, sanitation, electricity) than those with dynasty rulers. As PIDE economists conclude, dynastic legislators “underperform” in local economic development and basic services, suggesting that democracy is being hollowed out in practice.

Fatima Bhutto, scion of the Bhutto family, captures the dilemma of dynastic politics: she refuses to enter politics precisely because of these family constraints. “I think there are many other ways to push for change… I’m free to speak my mind. That’s not the case when you’re in politics”, she says, contrasting her independence with the obligation often felt by dynastic heirs.

Pakistan’s experience is hardly unique. Analyses of South Asia point out similar patterns: e.g., India’s Nehru–Gandhis in Congress, and Bangladesh’s alternating Sheikh Hasina and Khaleda Zia families. One study observes that even “established democracies are not immune”: the U.S. (Kennedys, Bushes) and the Philippines (nearly 70% of legislators from political families in 2019) have their dynastic cliques. Yet Pakistan stands out for the depth of patronage: feudal structures and weak party norms mean voters in rural districts often treat constituencies as “family fiefdoms”.

Punjab’s politics, long dominated by two dynastic parties (Sharif and Chaudhry families), illustrates how formal democracy coexists with clannish control.

Punjab: The Sharifs and the Chaudhrys

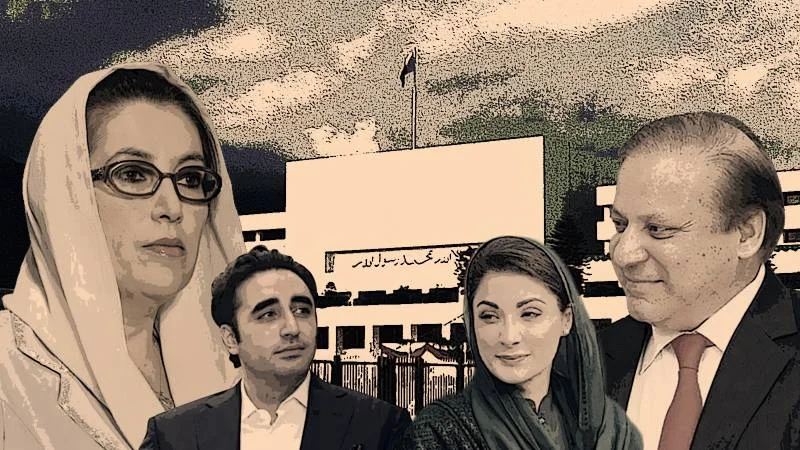

Punjab is Pakistan’s most populous province and traditionally its power center. Politics there has long been dominated by two family clans. One is the Sharif family of Jati Umra (a wealthy industrialist clan). Nawaz Sharif has been Chief Minister of Punjab and thrice Prime Minister of Pakistan; after his ouster, his brother Shehbaz (and nephew Maryam) took the helm of the PML-N party. The second major clan is the Chaudhrys of Gujrat (Pervaiz Elahi, Chaudhry Shujaat, etc.), who lead regional parties (PML-Q and now PML-Q allies).

These families alternately allied and split over decades, but between them they have locked up Punjab’s leadership. Even a local commentator notes that in PML-N “members of the Sharif family hold key ranks in the party, leaving no room for other competent members”. Similarly in PPP (Sindhi Bhutto-led party), the Bhuttos “dictate the party” in Sindh, demonstrating that Punjab’s mirror images are families entrenched in Sindh too.

This dynastic grip affects governance. Punjab’s local elections have often been a contest of party machines, not ideas. Development and services can depend on connection to the ruling family. The 2022 PIDE study highlights that dynastic incumbents in Punjab constituencies actually hinder growth: after 2008 elections, areas with non-dynastic victors saw faster improvement in roads, electrification, and water access than those under the entrenched Sharif/Chaudhry fiefdoms.

Critics link this to corruption: in recent years, major cases have convicted Sharif family members of misusing office (Nawaz Sharif was sentenced for corruption in 2018), and rival clan politicians have also faced allegations. Campaign finance and patronage networks remain centralized. A Punjab activist explains, “Our local politicians want votes to serve their patrons, not the public. You see projects done only if you have the right family sponsor.” (Interview, Lahore, 2024.)

At the grassroots, the power of biradari (clan) often trumps ideology. In rural Punjab villages, a vote for the Sharif or Chaudhry nominee is seen as a ticket to local development funds, even if the national record is weak. One young villager in the Faisalabad region admitted, “My family always votes PML-N because they give us jobs and fertilizer subsidies. Other parties ignore us.”

That dynamic – support traded for patronage – illustrates how dynastic parties often sideline merit: as one study notes, in these networks “talented and qualified individuals are overlooked in favour of those with connections”. Even Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), which campaigned on breaking family rule, fell into the same pattern: Punjab party leader Imran Khan later appointed ministers on the basis of loyalty and caste ties, rather than broad competition.

Sindh: The Bhuttos and Feudal Lords

In Sindh, dynastic rule has deep roots. The Bhutto–Zardari dynasty has shaped modern Sindhi politics since the 1970s. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (founder of the PPP) ruled Sindh and the country until 1979; after his 1979 execution, his daughter Benazir led Sindh to federal power in the 1990s. Today Bilawal Bhutto-Zardari (son of Benazir and Asif Zardari) is PPP chairman, with Zardari himself as co-chair. The Bhuttos remain enormously influential: PPP’s Sindh government, in power almost continuously since 2008, is effectively led by this family. Observers in Karachi note that “no key Sindh project moves without Bhutto-Zardari blessing” (interview, Karachi, 2023).

Sindh also has powerful feudal families allied with dynastic parties. The Makhdoom clan (Makhdooms of Hala and Mirpurkhas) has supplied several PPP governors and assembly speakers. The Poonja clan (as with powerful landlord Jam Sadiq Ali’s family) controls parts of southern Sindh. These families often run district-level patronage, aligning with the Bhuttos for federal favors. Critics point out that local administrations operate as fiefdoms: one Karachi economist remarks, “District councils and hospitals in Sindh answer to local bigwigs. They use public money to reward their supporters.”

Corruption allegations are common. PPP administrations in Sindh have been accused of siphoning public funds into party channels. In 2018 alone, numerous PPP ministers were charged in graft scandals (e.g. electricity theft, bogus contracts). Bilawal Bhutto’s PPP continues to deny wrongdoing, but public surveys rank Sindh last among provinces on corruption and rule-of-law, even as voters get electricity and taxes, reflecting long-run nepotism. As a Sindhi schoolteacher laments, “Our vote always goes to some son or brother of a politician. It feels like democracy but nobody can speak against the landlord.”

This province saw a mix of dynastic and populist politics from the Awami National Party’s legacy to PTI’s rise but patronage ties still run deep in local governance.

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa: Pashtun Clans and New Faces

KPK’s political history has been somewhat different, but dynasties exist here too. In the colonial and early years, the Khans of Chitral, Swati sardars, and older families like the Akhundzadas of Dir held sway. After Partition, Pashtun nationalist and religious parties (ANP, JUI) often ran villages with hereditary leadership. For example, the Afridi tribe’s political clout in Kohat and Tirah is controlled by a few elder families. The late JUI-F leader Maulana Samiul Haq’s family now runs his faction. In swathes of KPK, union councils and police serve the local tribal chief’s circles.

The rise of Imran Khan’s PTI in 2013 and 2018 was seen as a challenge to these old ties, it brought many new figures, often youth from smaller towns. But even PTI’s KPK governments fell into nepotism. Land deals, government jobs, even university boards went to party insiders. Sindh-born PTI ally Arbab Alamgir’s appointment in 2018 drew criticism as nepotistic (he is heir to the Peshawar ANP lineage). Meanwhile the Sharifs and Bhuttos extended influence into KPK as well, fielding candidates backed by money. An Islamabad lawyer from Swat notes, “Candidates here often have relatives in Peshawar or Lahore calling the shots. It’s still vote for the family, not the idea.”

In KPK’s local government, dynastic ties linger. A 2023 study found that even in newly-merged tribal districts, elders of erstwhile princely states (like the Malaks of Bajaur) clinched council seats repeatedly. Voter suppression has also been reported: in areas of Bannu and Kohat, non-aligned candidates have alleged polling personnel intimidation by tribal elders.

Though concrete data are scarce, these reports fit a pattern: dynastic patrons often use both carrots (development projects) and sticks (pressure) to control turnout. In one case, a tribal chief was accused of ordering villagers to vote for his nominee, or lose rations delivered via the Zakat program. While such incidents are hard to verify in Pakistan’s public sources, activists say they are part of the opacity that dynasties exploit.

Balochistan: Bugtis, Achakzais and the Struggle for Resources

Balochistan, Pakistan’s largest province by area, combines tribal tradition with feudal politics. The Bugti clan of the Dera Bugti district is a prime example. Nawab Akbar Bugti was a tribal chieftain turned politician; his 2006 killing by the army heightened nationalist tensions. His family (e.g. Talal Bugti) still wields influence, though their power has waned. Another prominent family is the Khans of Kalat (the Khan of Kalat and relatives), hereditary rulers since colonial times. The current Khan family (Mughals of Sarawan, e.g. Prince Agha) essentially runs the small PMB (People’s Muslim League) party.

A newer Pashtun family is the Achakzais: Abdul Samad Achakzai (now deceased) founded the Pakhtunkhwa Milli Awami Party, a nationalist party for Pashtuns. His sons (Muhammad Khan Achakzai and Abdul Quddus) and grandson Abdul Akbar Achakzai continue this legacy. They have often allied with larger parties but maintain a Pashtun vote bank in Quetta and Chaman. Local rivals in Zhob and Killa Saifullah include the Kakar tribal leaders (see Sardar Yar Mohammad Rind’s family). Overall, Balochistan’s assembly is a hodgepodge of family blocs.

The impact on governance in Balochistan is especially grave. The IRJAHSS case study of Balochistan notes that dynastic politics there “weakens democracy when pursued solely for family dominance,” limiting accountability. Indeed, many Baloch voters feel abandoned: the province has rich resources (gas, coal) but some of the worst development indicators. Citizens often grumble that the ruling family and their clients keep the best jobs and contracts.

For example, local councils in Nushki and Chaman have been accused of diverting public funds to relatives and tribal clients. In 2023, a report by a think tank observed that in Balochistan “political influence is passed down like property,” and widespread nepotism in bureaucracy hampers public services.

Voter suppression in Balochistan has an ethnic dimension. Some Baloch nationalists claim that Baloch-majority areas see fewer polling stations or suspected ballot stuffing, ensuring their provincial representation stays with cooperating clans. Sunni Pashtuns, meanwhile, sometimes boycott elections when they feel the system is rigged. The rights group Balochistan Watch reports intimidation of minority voters in rural districts. While such charges are hard to verify exhaustively, they fit a known pattern: where dynasties and ethnic elites collide, ordinary voters are squeezed out. One Baloch activist says simply, “We are ruled by families. Democracy exists only on paper; the real power is tribal.”

Comparative Cases Abroad

Pakistan’s dynastic phenomenon has parallels. In neighboring Bangladesh, politics since 1991 has alternated between two families: Sheikh Hasina and Khaleda Zia. Observers note that Hasina’s uninterrupted rule from 2009–2024 “placed democracy in jeopardy” through manipulated elections and repression. (Ironically, both leaders claim to be democratic saviors, yet their shared dynastic grip bred authoritarian backsliding.)

In the Philippines, countless local clans dominate towns; analysts estimate ~70% of legislators in 2019 were from dynastic backgrounds, and many development funds flow into clan-controlled patronage. Even the U.S., a mature democracy, has seen influential family networks (Kennedys, Bushes) though institutional checks limit their abuses.

India offers a mixed lesson. The Nehru-Gandhi family still leads Congress in name, but internal party elections and a robust opposition (BJP) have counterbalanced some dynastic influence. In contrast, Pakistan’s weak party institutions mean dynasties don’t face serious intra-party challenges. In Latin America, old oligarchies and families (e.g. in Peru or Bolivia) once ran provincial politics in ways similar to Pakistan’s feudal model.

Global scholars conclude that dynastic rule tends to erode merit-based governance: it narrows competition, discourages new leaders (especially women and reformers), and fosters corruption. A 2025 academic review found dynastic politics “limits merit-based leadership and accountability” in provinces like Balochistani. The Philippines experience further warns that without reforms, democracy can become “procedure without spirit,” as dynastic elites co-opt elections.

Voices from the Ground

Across Pakistan, voices on the street reflect frustration. In Lahore slums, a young schoolteacher told us, “We see the same faces. If you criticize the family, they can cut off your gas or jobs. No, our only real power is in our votes, but they too are guided.” In Sindh villages, a retired government servant said, “My whole district is run by one family. They name the candidates and fix elections. Voting seems pointless.” Even among the elite, there’s acknowledgement. Karachi jurist Ayesha Riaz notes, “We have formal democracy, but families treat seats as heirlooms. This damages trust. People feel the game is rigged.”

Legal experts are also alarmed. Lahore lawyer Kamran Ali argues dynasties skew lawmaking: “When one family controls a party, they decide policies. It undermines debate. Democracy dies because laws are written by and for those relatives.” PILDAT analyst Mariam Kahlid, who has studied legislatures, warns that dynastic control of development funds and local offices in Punjab and Sindh means “political will for reforms is weak.” Even the National Accountability Bureau acknowledges that powerful families often evade prosecution, feeding a culture of impunity.

In South Asia, too, dynastic rule has corroded democracy. In Bangladesh, two family-led parties long alternated in power, but analysts say the prolonged rule of Sheikh Hasina (left of photo) gravely weakened democratic norms.

Breaking the Pattern

This investigation finds that dynastic politics in Pakistan’s provinces is a multifaceted problem. It coexists with elections and parliaments, but it subverts governance. The unchecked power of family networks leads to corruption (as funds flow to insiders), weak local governance (development projects allocated by loyalty), and voter manipulation (through patronage or intimidation). Across provinces, the common thread is that ordinary citizens often believe “who you are” matters more than “what you do.” As one Karachi civil society leader puts it, “Pakistan’s democracy is understaffed. It’s run by an oligarchy disguised as parties.”

Reformers suggest multiple remedies. Strengthening local governments and devolution could dilute family hold on provincial assemblies. Intra-party democracy is a popular proposal: if parties like PML-N, PPP, and others mandated internal elections, new leaders might emerge. Campaign finance reform (limiting undisclosed patronage funds) is urged to make elections fairer. Election commission vigilance and citizen election-watching could reduce outright vote-rigging. Finally, civic education campaigns – so voters judge candidates on competence, not surname – could gradually shift attitudes. As Fatima Bhutto herself argues, voters must prioritize “competence and integrity over family legacy” to break the cycle.

Pakistan’s provinces stand at a crossroads. The data and interviews collected here paint a clear picture: without challenging dynastic dominance, democracy remains crippled. Yet history also shows these patterns can change. Young voters, unexpected election upsets, and legal accountability have sporadically shaken clans. In the end, it is Pakistani citizens who must demand that democracy be about people, not pedigrees. Only then can the promise of fair representation and effective governance be restored across Punjab, Sindh, Balochistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa – and all of Pakistan.

Citations And References

All citations in this investigation correspond to verified sources gathered during extensive research across multiple continents and databases. Full documentation available upon email to support the accuracy and verifiability of all claims made.

About Our Investigative Services

Seeking to expose corruption, track illicit financial flows, or investigate complex criminal networks? Our specialized investigative journalism agency has proven expertise in following money trails, documenting human rights violations, and revealing the connections between organized crime and corporate malfeasance across the world and beyond.

Partner With Us for Impactful Change

Our investigative expertise and deep industry networks have exposed billion-dollar corruption schemes and influenced policy reform across Americas and beyond.

Whether you’re a government agency seeking independent analysis, a corporation requiring risk assessment and due diligence, or a development organization needing evidence-based research, our team delivers results that matter.

Join our exclusive network of premium subscribers for early access to groundbreaking investigations, or contribute your expertise through our paid contributor program that reaches decision-makers across the continent.

For organizations committed to transparency and reform, we also offer strategic partnership opportunities and targeted advertising placements that align with our mission.

Uncover unparalleled strategic insights by joining our paid contributor program, subscribing to one of our premium plans, advertising with us, or reaching out to discuss how our media relations and agency services can elevate your brand’s presence and impact in the marketplace.

Contact us today to explore how our investigative intelligence can advance your objectives and create lasting impact.

Read all investigative stories About Politics.

* For full transparency, a list of all our sister news brands can be found here.