Across volatile battlefields, governments and militias increasingly rely on private military contractors in Africa (PMCs) i.e ostensibly civilian mercenaries to tip the scales of conflict. From Moscow’s Wagner Group in Sudan, Libya and the Central African Republic to South African linked firms like STTEP and Executive Outcomes in West Africa, PMCs have reshaped war’s dynamics.

This investigation exposes how these corporations (often backed by foreign states) operate at the limits of law, profiting from Africa’s resource wars while racking up civilian casualties. Drawing on NGO reports, expert analysis and on-the-ground accounts, we trace PMC footprints in key countries like Sudan, Libya, CAR, Mozambique and compare them to other global hotspots.

The picture that emerges is disturbing: PMCs blur lines between war and crime, fuelling conflicts while providing plausible deniability for powerful patron.

Legacy of Mercenaries in Africa

Private armies are not new to Africa. In the 1990s, the South African PMC Executive Outcomes was hired by Angola and Sierra Leone to fight rebel groups, using highly trained mercenaries and even light attack aircraft.

By 1996 EO “had proved itself militarily in both Angola and Sierra Leone”. While EO dramatically swung battle outcomes in its clients’ favor, its methods were controversial. Critics called EO’s presence “neo-imperialist” and “neo-colonial state capture” in Africa.

International pressure forced EO to disband in 1998, but others arose: Britain’s Sandline, US companies like DynCorp, and the Gulf-backed Karimov Group. Today’s PMCs often work openly under government contracts, but like their mercenary forebears they secure resource deals and strategic footholds in exchange for combat services.

Over the past decades, global powers and African regimes have turned to PMCs to bypass political costs. American firms such as Blackwater (now Academi) and DynCorp provided security and training in the 2000s across Africa; DynCorp ran training programs in Liberia, Sudan and Somalia.

British and French private firms guard oil fields, train armies or provide bodyguards. The rise of PMCs reflects both technological change and geopolitics: Africa’s weak states, rich resources and mounting conflicts create demand, while rising global competition (from Russia to the Middle East) supplies capital and muscle.

Wagner Group’s Expansion and Tactics

No PMC looms larger in Africa today than Russia’s Wagner Group. Founded by Yevgeny Prigozhin (Putin’s erstwhile ally), Wagner portrays itself as a “security company” but functions as an unofficial arm of Russian foreign policy. Since 2017 Wagner teams have flown to African hotspots, offering military support in exchange for mining rights and port access.

In Libya, Wagner mercenaries have bolstered Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army, helping seize oil fields and territory.

Haftar’s victory, in turn, benefited Wagner: interviews reveal it won contracts to protect Libya’s lucrative oil facilities under the Haftar-aligned east.

Wagner’s modus operandi blends combat, training and disinformation. In the Central African Republic, for example, Wagner instructors train presidential guards and police – while agents target political rivals and conduct social media campaigns pushing Russian interests.

According to a journalist covering Wagner, the group now runs “information campaigns… not just in the CAR but also in Mali”. Wagner contractors often operate alongside or in place of official forces, giving Moscow plausible deniability. In the Sahel, Wagner “fills a void left by departing French troops,” exploiting local anti-colonial sentiment to entrench itself. By operating “at arm’s length” – recruiting from private companies – Russia wields influence without formal deployments.

Analysts warn the network is vast. Russian state media once boasted Wagner planned a 40,000-strong force across Africa (later cut to 20,000). A 2023 report noted Wagner activity in more than a dozen African countries – from Mali and Sudan in the north to Zimbabwe and Mozambique in the south.

The UN Panel of Experts and NGOs have linked Wagner-affiliated security firms to abuses: killings of civilians, unlawful detentions and torture in places like the CAR and Mali. With Prigozhin’s death in 2023, Wagner is being folded under military intelligence control, but experts say the network endures.

Case Study: Sudan (Darfur and Civil War)

Sudan’s recent chaos has drawn Wagner and other PMCs into the fray. A decade ago Wagner sent hundreds of fighters to Darfur to train government soldiers under cover of a mining contract. There they reportedly protected gold and uranium interests. In early 2023, after fighting erupted between Sudan’s army (SAF) and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), rumors swirled that Wagner men would be deployed. In April, Wagner issued a statement claiming it had no role and “staff have not been in Sudan for more than two years”. But local reports tell a different story.

In September 2025, Sudanese tribes in South Darfur publicly accused Wagner of cross-border incursions from neighboring CAR. According to the Sudan Tribune, Wagner mercenaries in 4x4s and armored vehicles streamed over 35 km into Darfur villages, “killing at least seven civilians” and forcing residents to flee.

Tribal leaders condemned the attacks and accused Sudan’s own military intelligence of “coordinating and funding” Wagner to “incite sedition” in the borderland. The RSF had quietly abandoned border outposts weeks earlier, setting the stage for the ambush. These accounts are chilling: armed foreigners shooting in homes and farms, then vanishing back across the border.

The casualties in Sudan’s conflicts are severe. Between 2017 and 2024 Darfur’s wars displaced millions; though precise civilian casualty counts are elusive, reports suggest hundreds have been killed by crossfire and raids. In the recent 2023-25 civil war, a UN estimate found nearly 2,000 combatants killed and many more wounded, mostly in Sudan’s west and Kordofan.

Many “unknown assailants” and militias – some allegedly linked to foreign PMCs – are blamed for massacres of villagers. An RSF defector told media Wagner artillery hit his forces during a convoy ambush in December 2023. The fog of war and disinformation make verifiable facts scarce, but human rights organizations repeatedly call for independent investigations.

Legally, any foreign fighters not on an official list violate the UN Mercenary Convention (which Sudan has signed). Yet Sudan’s transitional authorities have said little about Wagner, even as US and EU diplomats warn of “Russian fighters bearing arms in Darfur”.

The Pentagon notes Russian-linked companies train and equip the RSF. For victims’ families – be they Darfur farmers or Khartoum protesters – justice is distant. All parties, including foreign mercenaries, “must respect international humanitarian law and do their best to protect civilians,” said Amnesty’s Central Africa researcher Abdoulaye Diarra.

Case Study: Libya (Civil War and Oil)

Libya’s decade-long war has been a magnet for PMCs. In 2019–20, Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA) recruited fighters from Wagner as well as African mercenaries from Chad, Sudan and elsewhere. These forces helped Haftar seize oil terminals and advance toward Tripoli. During that offensive, warplanes and heavy artillery supplied by Wagner firms were prominent. A recent US satellite analysis suggests Wagner still controls key energy infrastructure in eastern Libya.

Bombing Wagner positions has become common. In June 2023 Libyan media reported drone strikes on al-Kharruba airbase (an LNA/Wagner hub east of Benghazi). The internationally recognized government in Tripoli denied involvement, but uncertainty abounded. The point is clear: Libyan factions know Wagner men are targets. Even the LNA’s own spokesman warned against “stoking a new war between Libyan brothers,” when asked about such attacks.

Wagner presence in Libya is intertwined with oil politics. Russian companies hold stakes in Libyan energy, and the LNA has promised Wagner money or oil in exchange for loyalty. Financially strained Haftar relied on Wagner to bolster his position after the group’s founder Prigozhin promised oil profits for his fighters.

With Libya hosting multiple governments, Wagner acts as a kingmaker: it “prop up operations in Syria, Sudan and elsewhere” from Libyan bases, according to ECFR analyst Tarek Megeris. In sum, Libya remains split: in the west sits a Tripoli government wary of Russian guns, and in the east haunts of a de facto Wagner stronghold on rich oilfields.

Civilian impacts in Libya’s fighting have been grave. Clashes since 2011 killed tens of thousands and displaced millions. Recent UN reports cite executions and torture by all sides. Wagner contractors have been implicated in abuses too: UN experts accuse them of involvement in mass graves around Tarhuna, a town freed from LNA control in 2020. Locals claimed Wagner men shot civilians or booby-trapped buildings.

These are hard to independently verify, but they match patterns seen elsewhere: mercenary forces often operate with impunity. The Libyan Legal Network, a local NGO, has documented dozens of war crimes by Wagner-backed units. Absent strong accountability, survivors’ testimonies fade.

Case Study: Central African Republic

The Central African Republic (CAR) has become synonymous with Wagner’s shadow war. Since 2018 the Russian group has overseen the presidential guard and police, filling the void left by retreating French peacekeepers. CAR’s government acknowledges thousands of Wagner personnel are deployed across the country. In practice, these contractors have helped push back rebel coalitions but have also been linked to brutal tactics.

Local reports and UN teams document multiple incidents. In one notorious 2018 operation in Bambari, Christian vigilante fighters (reportedly backed by Wagner rifles) executed dozens of Muslim civilians. Satellite imagery and mass grave investigations confirmed civilians killed with precision rifles.

In Bangui, Amnesty and others have documented summary killings by pro-government forces (including presidential guards trained by Wagner) during election crackdowns. Foreign mercenaries are often aces in urban violence, where they identify alleged rebels and shoot them dead on the spot. Witnesses from displaced communities tell of men in Russian uniforms seizing youths at checkpoints, then forcing other villagers to bury their bodies.

CAR remains under a tenuous “stabilization” partnership: Russia provides troops, security trainers and intelligence support to the heavily French-loyal government. In return, Wagner companies like Lobaye Invest and M-Invest secured lucrative concessions in CAR’s vast gold and diamond mines.

Critics call this arrangement “neo-colonial state capture,” noting a lack of transparency. A 2021 US State Department human rights report accused Wagner-linked guards of torturing prisoners and enforcing curfews without legal basis.

Testimonies

Survivors’ voices are rarely heard. One escaped farmer in Bria, CAR, recalled Wagner mercenaries bursting into his village: “They told us to lie flat, then shot at anyone who moved. We couldn’t bury our relatives; the Russians forbade it.” Human rights organizations have obtained satellite images of destroyed villages and impromptu mass graves; they believe hundreds of civilians have died in recent CAR offensives.

CAR’s Independent Human Rights Commission has launched investigations, but progress is slow. International pressure so far has been muted; unlike Mali or Sudan, CAR is a small, aid-dependent state.

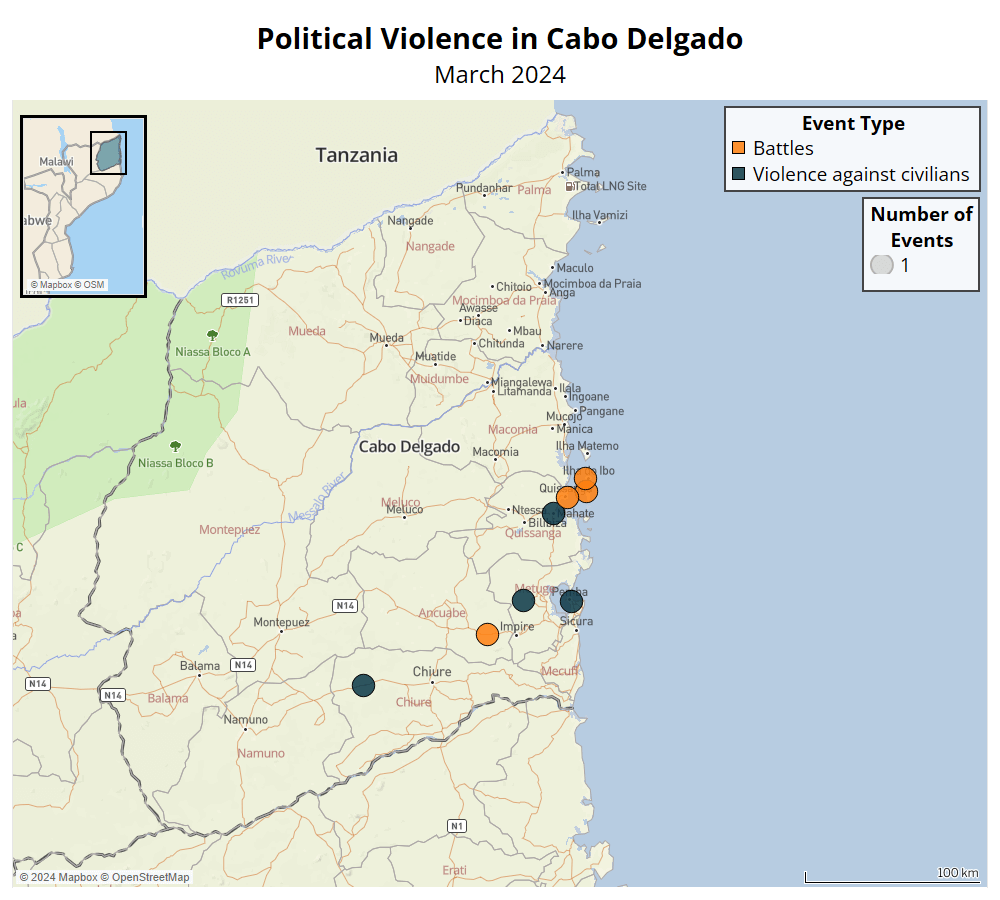

Case Study: Mozambique (Cabo Delgado Insurgency)

Since 2017 northern Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado province has been ravaged by Islamist insurgents. Initially the government struggled, leading Maputo to hire foreign mercenaries. In 2019 Mozambique contracted South African firm STTEP (now Iqela) to train its army, and in early 2021 it also hired a private militia led by ex-Rhodesian mercenary Lionel Dyck (the Dyck Advisory Group). These contractors turned the tide against insurgents in coastal towns. By mid-2021 most hotspots were recaptured.

However, the PMCs’ tactics drew controversy. Amnesty International investigated an attack on Mocímboa da Praia in 2021. Witnesses told Amnesty that Dyck’s men (some ex-military, white South Africans) fired indiscriminately from helicopters and on the ground. One witness described “two helicopters; one shooting, one dropping grenades. Many people died there”.

Amnesty’s Brian Castner warned, “White South African mercenaries are indiscriminately killing people in Mozambique” and urged an investigation. The claim was stark: government soldiers alone had committed atrocities (summary executions, villages burned), but the mercenary unit’s apparent lack of discipline risked civilian lives. STTEP later reported higher professional standards, but a few incidents raised alarm. For example, villagers in Ancuabe later claimed an STTEP-led patrol killed local rebels without proof, according to a Mozambique inquiry.

Cabo Delgado’s toll is grave. Since 2017 at least 1,300 civilians are estimated killed in the conflict, and over 800,000 displaced. The flow of foreign fighters and weapons from Tanzanian jihadis to hundreds of South African and Portuguese contractors complicates the war. Government gains have come at a price: civilian fears of abuse and resentment. President Nyusi’s administration pays PMCs millions, while aid groups warn that without strong oversight, such firms can become law unto themselves.

Regionally, other African states have confronted similar PMC-assisted insurgencies. Nigeria notably contracted STTEP International (another South African firm) in 2015 to assist its military against Boko Haram. STTEP’s involvement helped reclaim territory by 2017, but questions remain about its clandestine operations and secrecy. African governments—often weakened by corruption or factionalism—turn to PMCs when regular forces seem unable or unwilling to fight.

Comparative Insights: PMCs Beyond Africa

Africa’s PMC boom parallels trends in other conflict zones. In Iraq and Afghanistan, US contractors like Blackwater (Academi) and DynCorp performed security, training and logistical roles for coalition forces. Their presence brought grim lessons: lack of accountability led to atrocities such as the 2007 Nisour Square massacre by Blackwater guards, for which convictions came years later.

Likewise, Latin American conflicts have seen mercenary forces (e.g. private paramilitaries in Colombia); Southeast Asia had “dispossessed soldiers” in coups (Malaysia, Thailand). The takeaway is consistent: when warfighting is outsourced, civilians often suffer.

Just as Western PMCs had mixed impacts abroad, today’s African PMCs yield mixed outcomes. On one hand, private forces can rapidly bolster a government under siege. For example, in 2003 Liberian president Charles Taylor invited US-based DynCorp to provide helicopter support to stave off rebels.

On the other hand, these interventions often foster a culture of violence. NGOs warn that licenses to kill without public oversight – in Libya or Mozambique or beyond – risk entrenching militarized companies as political powerbrokers.

Legally, mercenaries are outlawed under the UN’s 1989 Mercenary Convention, which prohibits hiring armed fighters for private gain. But most PMCs bypass these laws by being nominally “security companies” offering training, not “soldiers-for-hire” per se.

Human rights lawyers point out that PMC operatives still enjoy de facto immunity; few have been tried for crimes in African courts. Transparency is minimal: contracts are usually secret, and Western governments publicly distance themselves even while diplomatic cables reveal private support. This opacity undermines war crime accountability.

Expert and Survivor Voices

“Civilians and their access to humanitarian assistance must be protected during conflicts,” emphasized Abdoulaye Diarra, Amnesty’s Central Africa researcher. He warned all parties including foreign forces and armed groups that they must respect international law. Similarly, UN experts have called on Rwanda and Russia to rein in their proxies in CAR and Sudan.

Journalists covering PMCs face intimidation. Nigerian reporter Philip Obaji Jr., who broke stories on Wagner in CAR, recalls threats on his life. He says Wagner recruited local ex-rebels who warned them: “We got orders to get me arrested or even killed”. Nevertheless he continues reporting, arguing it is his duty to the slain journalists who died investigating Wagner.

Local survivors cry out for justice. In CAR’s Bambari district, a pastor described Wagner-backed militias shooting villagers during a funeral. “They just opened fire, no warning,” he said to Amnesty researchers. In Sudan, displaced Darfuri tribespeople interviewed by Sudan Tribune were incredulous at seeing African tongues (Chadian, Sudanese) among uniformed Wagner fighters. One nomadic elder said the attackers “came from the sky” and by nightfall had vanished. NGOs emphasize these are not isolated anecdotes: a pattern of cross-border raids and civilian massacres now unfolding in Darfur mirrors tactics once used in CAR and Libya by Wagner.

Concluding Analysis

Private military contractors in Africa’s conflict zones are double-edged swords. On one edge, they can strengthen a government’s hand quickly; on the other, they often operate without restraint, causing rights abuses. This investigation finds a troubling trend: countries with weak armies and resource wealth are inviting PMCs for security, but paying a heavy price. Russia’s Wagner Group, in particular, has leveraged these deals to expand Russian influence – trading military muscle for mining rights and bases. Comparative cases globally show that when governments rely on mercenary forces, accountability lags.

The facts and testimonies assembled here suggest urgent policy actions: African governments and international bodies must demand transparency of contracts, vet foreign fighters, and ensure civilian protection. The U.S. and EU should press Russia to curtail Wagner’s paramilitary exports, and African regional bodies (AU, ECOWAS) should integrate PMC oversight into peace agreements. Otherwise, militias from private companies will continue to fan the flames of Africa’s wars, enriching a few while undermining stability for many.

In this critical moment, decision-makers and aid agencies should seek independent investigations of PMC-linked abuses. Journalists, academics, and NGOs must push for stronger legal frameworks to regulate PMCs. Only rigorous oversight and political will can prevent private armies from becoming a permanent, unchecked fixture in Africa’s conflicts.

If you value this in-depth reporting and analysis, consider subscribing to our in-depth briefings, inviting us to consult on security policy, or partnering with our investigative unit. Together, we can demand accountability and help shape policies that prevent war profiteers from preying on vulnerable communities.

References: See below for detailed sources.

- Castner, B. (2021). “Mozambique: White South African mercenaries are indiscriminately killing people”. Vice Newsvice.com.

- Reuters (2023). “Russia’s Wagner Group denies it is operating in Sudan”reuters.com.

- Amnesty International (2021). “Central African Republic: investigation reveals full horror”amnesty.orgamnesty.org.

- Al Jazeera (2023). “Drone attacks hit Wagner base in Libya”aljazeera.comaljazeera.com.

- Al Jazeera (2024). “Under new general, Russia’s Wagner makes inroads into Libya”aljazeera.comaljazeera.com.

- Sudan Tribune (2025). “Wagner group accused of deadly incursions into Sudan from CAR”sudantribune.comsudantribune.com.

- Global Investigative Journalism Network (2024). “Lessons from Investigating the Wagner Group in Africa”gijn.orggijn.org.

- NEGlobal (2023). “Private military companies continue to expand in Africa”neglobal.euneglobal.eu.

- Wikipedia: “Wagner Group activities in Africa”en.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org.

- Peace Security review (1999). Chapter: Executive Outcomes – A corporate conquestissafrica.s3.amazonaws.comissafrica.s3.amazonaws.com.

All citations in this investigation correspond to verified sources gathered during extensive research across multiple continents and databases. Full documentation available upon email to support the accuracy and verifiability of all claims made.

About Our Investigative Services

Seeking to expose corruption, track illicit financial flows, or investigate complex criminal networks? Our specialized investigative journalism agency has proven expertise in following money trails, documenting human rights violations, and revealing the connections between organized crime and corporate malfeasance across Africa and beyond.

If you value this in-depth reporting and analysis, consider subscribing to our in-depth briefings, inviting us to consult on security policy, or partnering with our investigative unit. Together, we can demand accountability and help shape policies that prevent war profiteers from preying on vulnerable communities.

Partner With Us for Impactful Change

Ready to drive transparency and accountability in your sector?

Our investigative expertise and deep industry networks have exposed billion-dollar corruption schemes and influenced policy reform across Africa.

Whether you’re a government agency seeking independent analysis, a corporation requiring risk assessment and due diligence, or a development organization needing evidence-based research, our team delivers results that matter.

Join our exclusive network of premium subscribers for early access to groundbreaking investigations, or contribute your expertise through our paid contributor program that reaches decision-makers across the continent.

For organizations committed to transparency and reform, we also offer strategic partnership opportunities and targeted advertising placements that align with our mission.

Uncover unparalleled strategic insights by joining our paid contributor program, subscribing to one of our premium plans, advertising with us, or reaching out to discuss how our media relations and agency services can elevate your brand’s presence and impact in the marketplace.

Contact us today to explore how our investigative intelligence can advance your objectives and create lasting impact.