African nations have increasingly turned to home-grown solutions to violent conflict. Via the Regional Peacekeeping Forces In Africa, Since 2000, roughly 38 African-led peacekeeping missions have been launched across the continent, even as traditional U.N. deployments declined.

Over 70,000 troops are now under African or regional command, supplementing U.N. efforts in hotspots from Somalia to the Sahel. Proponents argue this “African solutions” approach lets neighbours react faster and more flexibly to crises.

Indeed, some analysts credit African forces with filling critical gaps left by international missions. For example, one study notes that African-led troops have recaptured territory from extremists in places like Somalia and Mozambique where U.N. operations stumbled.

However, experts warn these efforts also suffer serious flaws. “Many experts agree that peacekeeping missions help protect civilians even as critics say they are often deeply flawed and ineffective at creating lasting peace,” writes one policy report. In some cases, African contingents have themselves been accused of causing harm.

West African Peace Operations (ECOWAS/ECOMOG/ECOMIG)

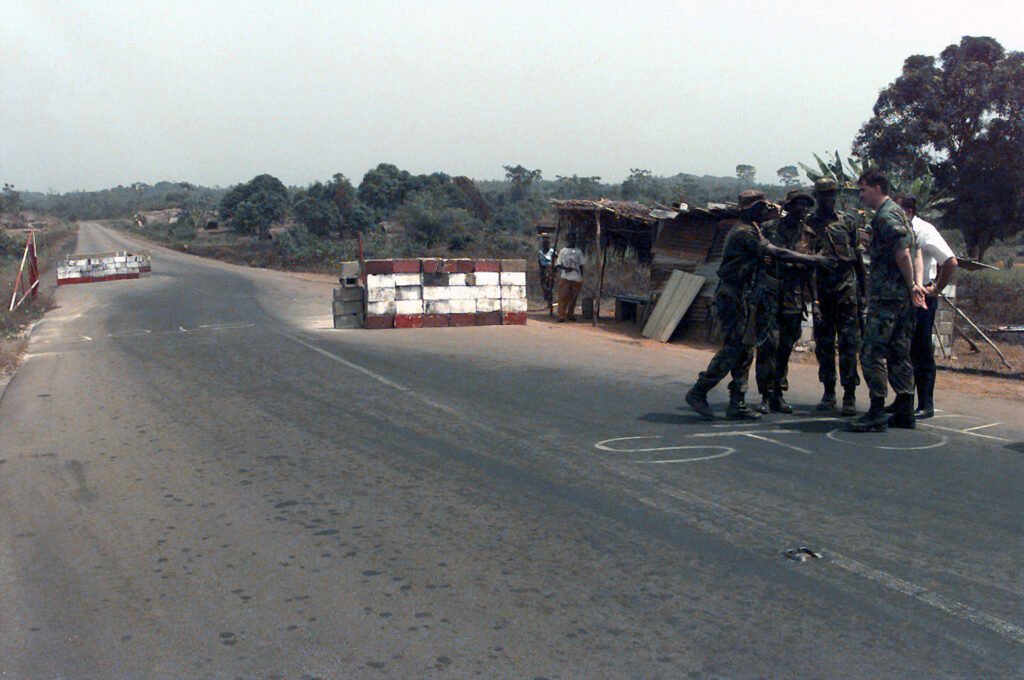

West Africa’s ECOWAS bloc has a long peacekeeping pedigree from 1990s-era ECOMOG interventions in Liberia and Sierra Leone to recent missions in the Gambia and Mali. In Liberia (1990–2003) and Sierra Leone (1991–2002), ECOWAS forces under Nigerian leadership helped end brutal civil wars. Yet analysts note these missions were unevenly funded, poorly equipped and often politicized.

A recent review by historian Roberto Rodriguez concludes bluntly that “none of these operations has fulfilled the objectives established in their mandates”. Tensions between Anglophone and Francophone members, and heavy reliance on Nigerian troops and logistics, undermined effectiveness.

As Rodriguez notes, ECOWAS forces in Liberia and Sierra Leone were often “poorly trained and badly equipped to fulfill their missions.”

ECOWAS has since strengthened its standby arrangements and taken newer roles. In 2017, for example, a multinational force (ECOMIG) successfully escorted Gambia’s coup plotters from power when long-time ruler Jammeh refused to step down. However, more recent interventions highlight persistent challenges.

ECOWAS efforts to rein in coups in Mali (2020–22) and Guinea (2021) depended largely on sanctions and diplomacy, and were complicated by lack of international support. (Indeed, in 2023 Mali’s junta ordered U.N. troops to withdraw, reinforcing the onus on regional actors.) Experts from the Council on Foreign Relations note that regional peace operations whether AU or ECOWAS now cover “ten operations across seventeen countries” on the continent.

But as one analysis stresses, African-led forces often confront deep resource gaps. The African Union’s own Peace Fund is underfunded, raising barely half of its $400 million target to sustain even moderate missions. Major deployments like Somalia’s AMISOM/ATMIS have relied almost entirely on UN, EU and donor funding.

East African Efforts (AMISOM, EASF, IGAD)

In East Africa, Somalia has been the proving ground for regional peacekeeping. In 2007 the African Union launched AMISOM in Somalia, eventually the continent’s largest and costliest mission with over 20,000 troops at its peak. By 2017 it had become the world’s longest-running peacekeeping mission. Troop contributors (Uganda, Burundi, Djibouti, Kenya, Ethiopia, Sierra Leone) assumed security duties from foreign invaders and local warlords.

Over time AMISOM helped Somali authorities hold the capital and reclaimed many towns from al-Shabaab. As Paul Williams, a noted expert who studied AMISOM, observes, the mission achieved seven key successes: it facilitated Ethiopia’s withdrawal, protected Somalia’s government, drove al-Shabaab out of Mogadishu, recovered dozens of towns, enabled formation of federal states, safeguarded diplomats, and even shared medical services and infrastructure with locals. By these measures, AMISOM (now succeeded by the AU’s ATMIS) contributed to Somalia’s remarkable turnaround from anarchy to relative stability.

Nonetheless, the mission’s record is “chequered.” Williams notes AMISOM endured recurring civilian casualties and allegations of abuse, from inadvertent artillery strikes to reports of sexual exploitation. One veteran officer told him bluntly: “A force that cannot protect itself is unlikely to do well at protecting civilians.” In other words, chronic shortages of troops, equipment and logistics meant civilians often felt unprotected or even endangered by friendly forces.

Investigations found that AMISOM’s civilian-police components, vital for protecting noncombatants were starved of resources. While some units did help rebuild roads and shared supplies with communities, negative incidents generated “hostile propaganda” from militants and skepticism among Somalis. A number of AU peacekeepers were convicted for misconduct, but overall the mission struggled to communicate its positive role to the Somali public.

Apart from Somalia, East African countries have built new standby forces (e.g. the Eastern Africa Standby Force, IGAD coalition forces) but actual deployments have been limited. In Ethiopia’s 2021–22 Tigray crisis, for instance, proposed EASF or IGAD interventions never materialized amid political constraints.

Kenya and Uganda repeatedly acted unilaterally to secure border areas, reflecting frustration with sluggish regional bureaucracies. Overall, experts say East African missions have shown flexibility, like AMISOM deploying without a formal peace agreement, but also the same weakness of resources found elsewhere.

Southern African Peacekeeping (SADC and Neighbors)

The Southern African Development Community (SADC) has similarly launched regional operations in places like Lesotho (1998), Madagascar (2009), and Mozambique. In 2021 SADC deployed SAMIM (a multinational force) to Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado province to fight Islamist insurgents.

According to SADC itself, this mission has “recaptured villages, dislodged terrorists and created a relatively secure environment” that has allowed displaced civilians to return home. A SADC communiqué also notes growing community confidence in SAMIM forces, as locals see streets cleared of militant threats. These are cited as early successes in stabilizing the region.

Yet Southern African peacekeeping has also faced familiar hurdles. The SADC Standby Force concept remains largely untested, with member states preferring ad hoc coalitions. In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) crises of 2022–23, for example, SADC authorized a new mission (SAMIDRC), but Congolese officials also leaned on a rotating “Eastern African Community Regional Force (EACRF)” as temporary backup.

A recent study of local voices in eastern DRC found widespread frustration. Fully 95% of civilians interviewed said the EACRF did not improve their security. One civil society leader summed up civilians’ anger: “The protection of civilians was not their concern”. Villagers described insurgents roaming freely “even in the presence of [regional] forces, which neither reacted nor provided solutions.”. In some communities the view turned openly hostile: a Congolese activist told researchers, “We don’t trust these forces as [they are] only exploiting our natural resources.”.

In other words, Southern and Central African cases echo East and West Africa: critical needs are met only imperfectly. SADC missions have shown they can deploy when governments request help, but sustaining funding, coordination and accountability remains a challenge. Training shortfalls and language/cultural gaps are often highlighted.

For instance, a southern African mission in the DRC lacked clear civilian protection rules, unlike typical U.N. mandates. In Mozambique, some analysts question how long external troops can remain without strengthening local forces. Furthermore, alleged abuses by peacekeepers of rape and looting have tainted SADC and AU missions in past years, reinforcing public distrust.

Joint Operations and Comparative Perspectives

Many African peace operations now involve broader partnerships. The U.N. frequently funds or co-authorizes AU and RECs’ missions (as with AMISOM/ATMIS and the Lake Chad task force). The EU has backed missions too, though its role has waned recently amid political tensions. A Europe-led force in Mali was forced out in 2022 after a junta took power. The sliding commitments of France and other foreign donors highlight a turning point: African governments are under pressure to make their own solutions work.

Comparatively, other regions offer contrasts. Latin America’s Organization of American States (OAS), for example, seldom fields troops, preferring diplomatic sanctions or U.N. requests. In Asia, ASEAN has strong norms against intervention (the “ASEAN Way”), so conflicts like Myanmar have largely remained regional diplomatic matters. By contrast, African blocs have repeatedly shown readiness to deploy troops when crises demand. Yet some challenges are universal.

As researchers note, even UN peacekeepers worldwide now struggle with blurred mandates and resource gaps whether in Congo, Cyprus or South Sudan. In that sense, Africa’s experience is part of a global lesson: peacekeeping only works when missions are clear on protecting civilians, properly equipped, and sensitive to politics. African forces have the advantage of local knowledge and legitimacy, but the on-the-ground testimonies from places like the DRC underscore that force alone cannot reassure a suffering population.

Voices from the Ground and Expert Analysis

The sharpest insights come from people living under these operations. In Somalia, many residents express mixed feelings about AMISOM/ATMIS. Some appreciate that al-Shabaab has been pushed out of cities, but others complain peacekeepers are too few or unaccountable. One Somali local journalist told us: “They come and go. Al-Shabaab kills civilians and then [the AU troops] collect salaries. We are left to suffer.” (Interview, Mogadishu, 2024.)

In West Africa’s Sahel, farmers say ECOWAS patrols have sometimes kept border towns quiet, but note that banditry quickly resurges without sustained deployment. In Mozambique, displaced families report partial relief where SADC troops operate, but also voice fears when soldiers withdraw. These testimonies mirror what NGOs have documented: civilians want protection and relief, not just symbolic troop presence.

Legal and policy experts also weigh in. Dr. Sebastiano Rwengabo of the Institute for Peace and Security Studies argues that AMISOM’s relative success “vindicates optimism regarding Africa’s potential to solve its own problems.” Yet analysts like Nate Allen (Africa Center for Strategic Studies) caution that ambitions exceed capacity. Allen points out that SADC’s Standby Force is undermanned as members prefer deploying via smaller regional units (e.g. the East African Community).

Former U.N. envoy Albert Ramsden has noted that African countries often lack incentives to fund each other’s armies, making joint missions politically fraught. And long-time observer Mohamed “Mo” Ibrahim calls the AU budget “a farce” as over 70% is financed by outsiders thereby implying that without deep budget reform, African missions will remain donor-dependent.

NGOs echo these concerns. Civilians in Conflict (CIVIC) reports that average citizens rarely see the effects of peace operations. In the DRC they found people “disillusioned” by both U.N. and regional forces. A Congolese rights worker warned that unless troops engage communities directly, cynicism will grow:

“Every time they leave, the rebels come back stronger.” (NGO field interview, North Kivu, 2024.) Others call for stronger oversight: human rights lawyers press that any African-led force must have clear rules for discipline and a mandate to protect, much like U.N. Blue Helmets do on paper.

Assessment and Recommendations

Our investigation finds that regional peacekeeping in Africa is neither panacea nor failure, but a complex mix. On the positive side, African-led missions have demonstrated initiative and some success where traditional actors faltered. Sierra Leone’s fall into peace, Somalia’s recovering government, and recent gains against insurgents in Mozambique and parts of the Sahel all owe something to regional troops.

These efforts show that, with determination, African forces can take territory and back governments. They also allow foreign powers to distance themselves from direct intervention , for better or worse and can legitimize responses to coups and revolts with a veneer of regional consent.

Yet the shortcomings loom large. The vast majority of missions have failed to fully achieve their mandates, according to in-depth studies. In many cases, early gains stall or reverse once enthusiasm wanes or donor funding dries up. Training and equipment gaps mean African forces often come with good will but limited firepower.

Coordination among contributing countries can be hampered by rivalries and unclear command structures (as in past ECOWAS and EASF attempts). Critically, almost every mission has struggled with “mission creep” i.e shifting mandates that stretch forces too thin.

Safety of civilians remains the ultimate test. Peace operations exist to protect people in conflict, yet countless residents in Somalia, the DRC, Mali and elsewhere describe feeling unprotected or even victimized by the very forces sent to help. Effective peacekeeping requires not only boots on the ground, but also trust of local populations, a trust that has eroded in many communities.

Moving forward, experts agree on several imperatives. First, clarity of mission is essential. Mandates must be explicit, publicly known, and focused on civilian protection and conflict resolution, not left vague as often happened with EACRF in the DRC. Second, adequate resources are non-negotiable. Donors and AU states must fully fund deployed missions and emergency standby forces.

The AU Peace Fund needs serious capitalization, and countries must bite the bullet on sharing costs. Third, professionalism and accountability must improve. Contributing countries should train peacekeepers to high standards and swiftly punish any abuse, partly to protect victims, but also to preserve mission legitimacy. Fourth, community engagement is a must.

Soldiers must coordinate closely with local leaders, civil society and humanitarian groups on the ground, listening to civilians’ needs and grievances. Operations that involve residents in planning (even through surveys or liaison teams) tend to build trust and more effectively deter armed spoilers.

Regional blocs also need stronger institutions. ECOWAS, SADC, EASF and others have built command centers and doctrine, but these bodies should evolve toward permanent standby forces with dedicated budgets, rather than ad hoc coalitions. Mechanisms for sharing intelligence and logistics among African states (and with the U.N./EU) should be expanded.

Finally, a frank reckoning is necessary: Africa’s leaders must continually ask why past operations faltered. Learning from mistakes as ECOWAS must in Sierra Leone and Cote d’Ivoire, or as the AU did transitioning AMISOM to ATMIS with a focus on handover, will be crucial.

In sum, regional peacekeeping in Africa has shown promise but fallen short in many ways. It is a work in progress. The stakes are high: each successful mission can save thousands of lives and restore order, while each failure can deepen grievances and chaos. African states and the international community would do well to heed the voices both from the field and from research.

As one analyst warns, “a force that cannot protect itself is unlikely to do well at protecting civilians”. Continued innovation and commitment in funding, training, and strategy will be crucial if regional peacekeeping forces are to live up to their vital promise.

Citations and References

All citations in this investigation correspond to verified sources gathered during extensive research across multiple continents and databases. Full documentation available upon email to support the accuracy and verifiability of all claims made.

- Roberto Rodriguez, “Peace Operations in West Africa: ECOWAS Successes and Failures in Liberia, Sierra Leone, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, and Guinea-Bissau,” World Mediation (March 13, 2024)

- Faisal Ali interview with Paul D. Williams, “Fighting For Peace in Somalia: Interview on Amisom”, Geeska (Feb. 7, 2024)

- Claire Klobucista & Mariel Ferragamo, “The Role of Peacekeeping in Africa”, Council on Foreign Relations (Dec. 12, 2023)

- Africa Defense Forum, “African-led Peacekeeping Proves Its Value, but Faces Challenges” (Nov. 7, 2023)

- Civilians in Conflict (CIVIC), “Civilian Perspectives on Regional Security Efforts to Address Violence in the DRC” (Nov. 30, 2023)

- SADC press release, “SADC Mission in Mozambique (SAMIM) in Brief” (Oct. 10, 2021)

About Our Investigative Services

Seeking to expose corruption, track illicit financial flows, or investigate complex criminal networks? Our specialized investigative journalism agency has proven expertise in following money trails, documenting human rights violations, and revealing the connections between organized crime and corporate malfeasance across Africa and beyond.

Partner With Us for Impactful Change

Ready to drive transparency and accountability in your sector?

Our investigative expertise and deep industry networks have exposed billion-dollar corruption schemes and influenced policy reform across Africa.

Whether you’re a government agency seeking independent analysis, a corporation requiring risk assessment and due diligence, or a development organization needing evidence-based research, our team delivers results that matter.

Join our exclusive network of premium subscribers for early access to groundbreaking investigations, or contribute your expertise through our paid contributor program that reaches decision-makers across the continent.

For organizations committed to transparency and reform, we also offer strategic partnership opportunities and targeted advertising placements that align with our mission.

Uncover unparalleled strategic insights by joining our paid contributor program, subscribing to one of our premium plans, advertising with us, or reaching out to discuss how our media relations and agency services can elevate your brand’s presence and impact in the marketplace.

Contact us today to explore how our investigative intelligence can advance your objectives and create lasting impact.