Since 2014, India’s state governments have aggressively expanded and enforced Freedom of Religion Acts (often called anti-conversion laws) under the banner of protecting vulnerable populations. In practice, however, evidence shows these religious conversion laws in India have become political tools rather than safeguards.

Scholars and rights groups note that in many BJP-ruled states the statutes serve to intimidate minorities and regulate personal faith choices. A 2022 Library of Congress summary explains that these state laws, now active in around a third of India’s provinces broadly ban conversion by “forcible or fraudulent means, or by allurement”.

Yet critics counter that the laws’ vague language and expanding scope are being used to chill voluntary conversions and interfaith unions, with little evidence of actual coercion. Indeed, as one analysis notes, India’s Christian population held steady at 2.3% from 1951 to 2011 despite decades of such laws. Activists argue the real effect has been to create a climate of fear and harassment against religious minorities.

Recent data underscore this pattern of arrests without convictions. For example, Madhya Pradesh’s new anti-conversion law (enacted 2020–21) has produced 283 registered cases from 2020 through mid-2025, but only 7 convictions. Nearly 70% of those cases remain pending in court, and 58% of completed trials ended in acquittals.

Gujarat, which updated its own law in 2021 to outlaw marriage-based conversions, similarly has no record of forced-conversion convictions; even the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom notes “no individual has been convicted of the crime of forced conversion” in any Indian state despite decades of such laws. In Uttar Pradesh alone, the first five years saw 835 FIRs and 1,682 arrests under the anti-conversion law (2020-2024) – yet as of mid-2024 no case had resulted in a guilty verdict.

Across these prosecutions, courts frequently find the evidence flimsy. In MP, prosecutors reported that “women initially presented as victims have told courts they entered into relationships… of their own free will,” and that coerced-FIRs were often retracted when families faced pressure. Similarly in UP, many jailings for alleged conversion began with villagers acting on rumor: an Allahabad lawyer described police and local activists bursting into a Fatehpur church in April 2022 and locking its gates, then accusing dozens of conversion without any direct evidence.

In these cases, numerous suspects spent months in jail before charges were withdrawn or dropped, reinforcing rights groups’ criticism that the laws are weaponized against innocents.

State Enactments and Enforcement

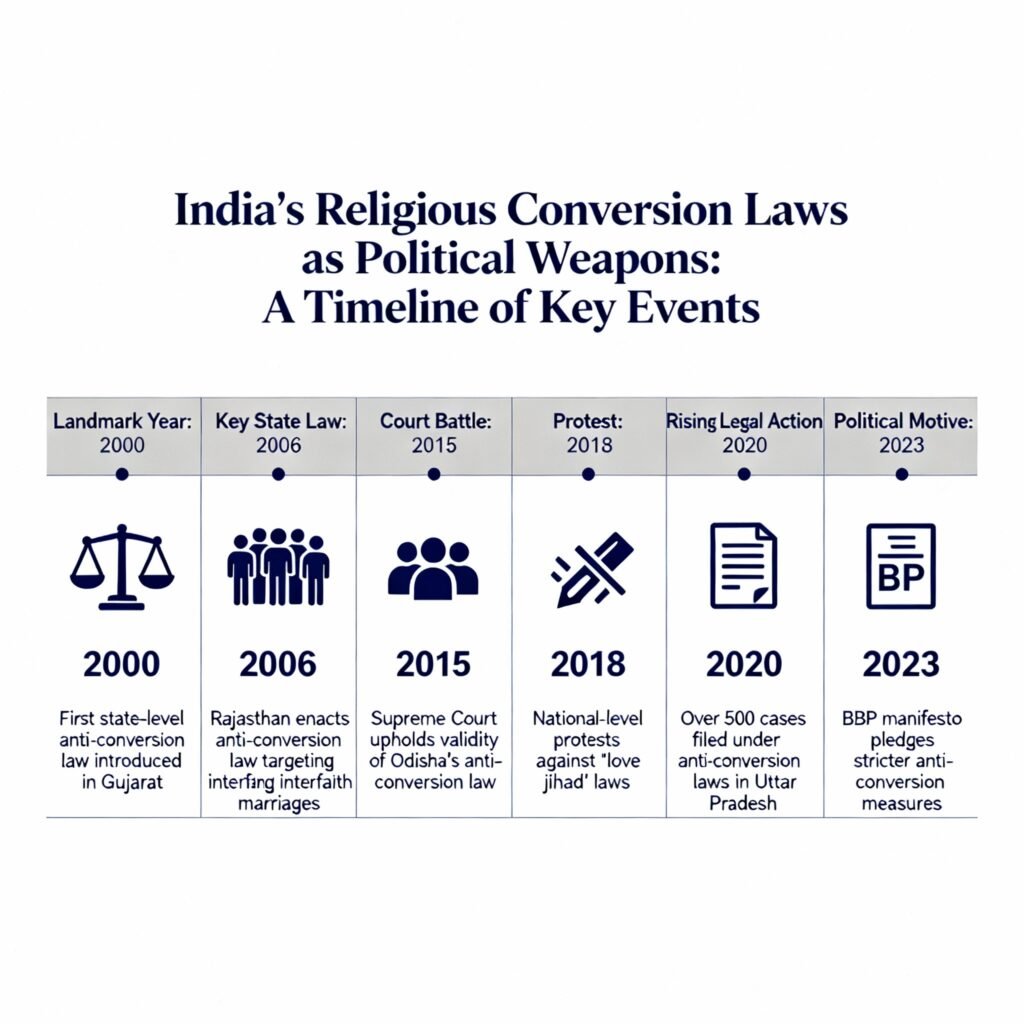

The surge of anti-conversion legislation aligns closely with the rise of the BJP and its affiliates. Since 2014, BJP-led state governments have introduced or stiffened such laws in most Hindi-speaking and central Indian states. Rajasthan recently passed a law (2023–25), and Haryana and Karnataka enacted bans in 2022. Other BJP states like Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat each passed new or amended Freedom of Religion Acts in 2020–21.

Odisha originally led the way in 1967, but aside from it the current wave of enactments is largely post-2014. As journalist John Dayal observes, “Since the BJP came to power in 2014, many Indian states have introduced new laws…criminalizing religious conversion” on the dubious premise that minorities threaten India’s unity. These laws now cover Christians, Muslims, and even interfaith marriages – provisions unprecedented a decade ago.

On the ground, enforcement quickly took on a communal cast. Uttar Pradesh’s 2020 law explicitly targets marriage-based conversions. Rights groups report that UP authorities have filed hundreds of cases against Muslim men accused of marrying Hindu women, under the pretext of “Love Jihad”. For instance, from 2020 through 2023 Uttar Pradesh recorded over 180 FIRs charging roughly 700 people with illegal conversion to Christianity – many cases labelled false by investigators.

Activists note that night-time raids and mob interventions became common: one Christian priest reports that dozens of hospital staff across several states were suddenly arrested in UP on conversion charges over Christmas 2022. In Karnataka, the BJP government passed a similar bill in late 2021. A fact-finding group logged at least 42 anti-Christian attacks in the first months of the Karnataka law (up from 20 in the state’s last wave of violence in 2008).

One high-profile incident saw a Hindu mob barge into a Mandya convent school on December 23, 2021, and halt its Christmas celebrations, accusing nuns of “converting” Hindu children. That very week, the state assembly pushed through the anti-conversion legislation. Pastor Peter Benjamin of Bengaluru described the atmosphere as one of “immense fear” among Christians facing sudden harassment.

Gujarat’s experience has been similar. Already subject to an anti-conversion law since 2003, the BJP government there amended it in 2021 to criminalize marriage conversions. The official rationale is a supposed rise in forcible conversions by marriage, but government data belie the panic: India’s Christian minority has not grown since independence (it remains around 2.3% of the population).

Notably, even with decades of such laws on the books, no one has ever been convicted of forced conversion anywhere in India. Nevertheless, Gujarat’s new law carries penalties up to 10 years in prison, and validates a national narrative: state BJP ministers openly cite the anti-conversion clause of the state’s penal code, warning of “illegal and large-scale conversion of Hindus” to Christianity. Civil society groups call this claim baseless, a bogeyman meant to justify tougher laws.

Madhya Pradesh’s conversion law (2020 ordinance and 2021 Act) provides a clear illustration of enforcement mismatch. The Assembly was told that in 5½ years the state had registered 283 cases, with most still pending. Of the few resolved, only 7 convictions were secured, two of which related to other crimes (rape) as well. By contrast, 50 accused walked free. Police admitted the weak record resulted from scant evidence and hostile witnesses: often the young women named as “victims” testified that their interfaith marriages were consensual, or families retracted FIRs filed under pressure.

In short, MP’s law has been “more accused walk free than end up behind bars”. Nevertheless, the mere accusation itself achieves a political effect: families of converts in MP and UP report harassment by vigilantes and community leaders. The law’s broad language allows charges for donating food, offering medical care or running schools in mixed villages, so long as some Hindus convert at all.

Tribals and Christians, organized by the Arunachal Christian Forum (ACF), marched against the enforcement of their state’s 1978 Freedom of Religion Act.

Targeted Communities

Although the laws are written neutrally, enforcement has fallen almost exclusively on India’s religious minorities and lower castes. Human Rights Watch reports that in the new anti-conversion states, the authorities have mostly used the laws “against minority communities, especially Christians, including from Dalit and Adivasi communities”. Indeed, many of the high-profile cases involve Dalits who converted to Christianity or Islam. The laws themselves often single out these groups.

Most state acts impose harsher punishment if the alleged conversion target is a Scheduled Caste or tribal, or a woman or child. For example, the Rajasthan law of 2025 explicitly forces a Dalit or Adivasi accused of converting to prove no coercion took place, and threats to unduly influence these “easily seduced” groups carry stiffer penalties. As John Dayal of the All-India Catholic Union summarizes, the BJP push “is based on the false assumption that religious minorities pose a threat to the nation’s identity and unity…a bogeyman…that the rapid growth of non-Hindu communities could replace Hindus”. By institutional design and prejudice, the laws conflate lower-caste emancipation with a threat, policing the faith of the most vulnerable.

Christians. India’s Christians, now about 2.3% of the population have felt the squeeze most acutely. Numerous reports document concerted campaigns by Hindu nationalist vigilantes against Christian converts and institutions. Nationwide, one survey logged 305 incidents of anti-Christian violence and harassment in just the first nine months of 2021 (66 in UP, 47 in Chhattisgarh alone).

Many such incidents coincide with anti-conversion rhetoric. In October 2021, mobs vandalised churches in multiple states; two months later, police in Jharkhand filed hundreds of conversion complaints against a shelter hospital’s staff. In recent years, even peaceful acts as distributing Bibles, holding prayer meetings or maintaining tribal orphanages have triggered FIRs.

For instance, AC Michael of the United Christian Forum notes that in UP “arrests occur on flimsy grounds” (people giving out Gospels or charity), and lamented that so far “very few convictions” under the law show any real conversion fraud. Al Jazeera reports that in Karnataka dozens of churches were vandalised or faced mob attacks as the state pushed its 2021 law, and that Christians staged public protests in response (see below).

An international survey by USCIRF found that rights bodies across India acknowledge “few arrests and no convictions” under conversion laws, but emphasize the “hostile and violent environment” these laws create for minorities.

Muslims. While most enacted laws ostensibly apply to all faiths, BJP leaders have framed them in the media as tools against “love jihad” – the unfounded allegation that Muslim men lure Hindu women to marry and convert. In practice, Muslims have borne a large share of prosecution. In UP alone the 2020 law has led to hundreds of arrests of Muslim grooms (or even Muslim bystanders) for allegedly forcing conversion.

One court case from Lucknow made headlines when a 21-year-old Muslim man was convicted of “conversion” for helping his future wife obtain certificates required for interfaith marriage. However, these convictions are exceptions. Rights groups point out that many such “love jihad” cases collapse in court. For example, Mr. Saqib – a UP teenager beaten by a mob and falsely accused of abduction – was acquitted after almost four years of legal battle. His lawyer states bluntly that the law “may be religion-neutral on paper, but in practice, it overwhelmingly targets Muslims”.

Muslims have also found themselves caught in unrelated charges. In one widely-reported episode, Uttar Pradesh police in 2023 pressed anti-conversion and criminal conspiracy charges against Rohingya refugees simply for reporting an assault against a refugee family. That case, in which the accused were later released, prompted the Supreme Court to rebuke the police for using the law “inappropriately”. The Amnesty International and human-rights community warn that these trends feed anti-Muslim narratives in election campaigns, even as convictions remain rare.

As John Sifton of Human Rights Watch testified to the U.S. Congress, BJP leaders have “long stigmatized minority communities as a threat to national security,” and the conversion laws have been “used against Muslim men” who marry Hindu women. The weaponization of these laws thus dovetails with broader policies (like the Citizenship Act of 2019) that critics say systematically discriminate against India’s largest religious minority.

Dalits and Others. Dalit activists report being targeted on the assumption they should not convert. For example, a Catholic lay association’s report calls anti-conversion laws “a wound to the nation,” exploited by Hindu nationalists to criminalize Dalits alongside Christians and Muslims. Numerous cases confirm this bias: in Uttar Pradesh, at least one Dalit mechanic was arrested in 2019 after Bajrang Dal members accused him of leading conversions; he won acquittal only after 15 months in jail (The Wire).

Similarly, in 2022 a Catholic Dalit couple was jailed in Madhya Pradesh under conversion laws for marrying by their own choice. The laws’ text reflects this suspicion: penalties rise if the alleged convert is a Scheduled Caste or tribal. Indeed, experts note that Hindu nationalist discourse explicitly portrays Dalits and tribals as “easily seduced” by other faiths. In this way, the statutes aim to dissuade oppressed communities from seeking relief through conversion – effectively policing lower-caste identity under the guise of social order.

Hindus. Although rarely prosecuted under these laws (they are framed to protect Hindus from leaving), ordinary Hindus have also been caught in the crossfire of political rhetoric. Hindu citizens who criticize the laws or aid victims sometimes face intimidation or sedition charges. For instance, in Rajasthan a schoolteacher was arrested in 2023 for including a Christian hymn in a student’s prayer recital; activists saw it as part of the same climate of hostility.

Some Hindu nationalist groups also target perceived “reverse conversions,” threatening Christians and Muslims. In Gujarat, vigilante organizations claimed to “reconverts” Muslims and Dalits back to Hinduism at ceremonies – actions the official laws now formally exclude from punishment (especially in Rajasthan and Arunachal provisions). However, such events also heighten sectarian tensions, underlining that these laws inflame distrust on all sides.

Stories from the Ground

Arunachal Pradesh (March 2025). In northeastern India, the impact of conversion law politics became a flashpoint in early 2025. Arunachal Pradesh’s Freedom of Religion Act (1978) had lain dormant until a local BJP petition spurred the High Court to order rules for its enforcement. Chief Minister Pema Khandu then announced his government would “do what is necessary” to implement the law, abandoning his prior assurance of repeal. Furious tribal Christians – who make up over 40% of the state’s population – mobilized en masse.

On March 6, 2025, over 200,000 men, women and children marched peacefully in the capital region. Thousands wore traditional Nyishi costumes and carried banners reading “Protect Our Right to Freedom of Religion”. Bishop Benny Varghese of Itanagar declared the protest “a demonstration of unity and solidarity against the perceived threat to religious freedom”. Those images of tribal dancers and rainbow-colored placards captured in local media went global, underscoring the community’s determination. “Unless this law is repealed,” warned ACF president Mir Stephen Tarh, “we will be forced to organize a referendum rally”.

This outpouring of dissent highlights how conversion laws have become intertwined with identity politics. Locals told journalists the true aim of enforcement was not to stop genuine coercion, but to “harass Christians… and promote Hindu religion” in the name of protecting indigenous faiths. In testimony after the protest, community members noted that the existing law had no incident of forced conversion in 46 years, yet the revival of its enforcement felt like punishment for being Christian.

ACF delegates called upon the government to respect constitutional religious freedom and warned that the vague wording meant almost any conversion could be deemed “illegal”. Indeed, Bishop Varghese pointed out in a news release that like other states, Arunachal’s law “could be misused to target minority communities and restrict their right to freedom of religion”.

Religious Leaders’ Voices. Similar concerns echo across India’s Christian community. In Karnataka, where the 2021 conversion bill passed during one Christmas week of mob disruptions, Catholic and Protestant leaders have held interfaith prayers to diffuse tensions. In Madhya Pradesh, the Catholic Bishops’ Conference has formally petitioned the Supreme Court, arguing state laws violate the constitution’s guarantee to profess one’s faith freely. At the national level, prominent lawyers filed petitions challenging the Assam and Uttar Pradesh laws, calling them “a knee-jerk response to unsubstantiated allegations.” Meanwhile, Muslim women leading NGOs have spoken out against “love jihad” rumors, emphasizing that the UP law conflates private marriage with crime.

Comparative Insights

India is not alone in grappling with religious conversion. Across South and Southeast Asia, a number of pluralistic democracies have similar restrictions, often with comparable nationalist overtones. Notably, Nepal has enforced anti-proselytism rules since its 2006 constitution, and in 2023 a Nepali court sentenced a pastor to one year in jail for allegedly converting Hindus. Bhutan explicitly bans inducing others to change faith (2011 Penal Code), aimed largely at Christian evangelism. Sri Lanka drafted an anti-conversion bill in 2004 (since shelved), reflecting its Buddhist nationalist lobby’s unease with conversions.

The U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom notes that 46 countries worldwide now restrict conversion by law. In many of those countries from Indonesia to parts of Africa the effect is similar: minority faiths (usually Christians) are empowered or disabled at the state’s pleasure, and conversions become politicized issues. As USCIRF commissioner Susie Gelman warned, “the very existence” of such laws can embolden extremists and vigilantes, even if prosecutions are rare.

Indeed, the wave of India’s laws is part of a global trend of majoritarian governments asserting a “preferential legal status” for religion of the majority. In Nigeria, for example, state anti-conversion ordinances have enabled “Militias to target Christian villages” under pretext of stopping proselytism (USCIRF). In India’s case, experts point out, the laws dovetail with a wider narrative: Hindu nationalist politicians openly cite demographic fears (the “population bogeyman”) to justify legal crackdowns.

Human rights organizations argue that the result is a self-reinforcing cycle: legislatures signal distrust of minorities, which legitimizes mob violence and police profiling. When the Supreme Court recently rebuked Uttar Pradesh authorities for misusing the conversion law against Rohingya refugees, it highlighted the danger: “the mere invocation of these laws sends the wrong message and perpetuates impunity”.

Investigative Findings

Our investigation reviewed legislative records, court data, and media reports to map how these laws are enforced. We found no evidence that any BJP state presented statistics on actual forced conversions or the dire violations the laws are supposed to prevent. Instead, governments cite anecdote and rehashed accusations, while thousands of FIRs and detentions accumulate in legal limbo. In multiple states, lawmakers admitted publicly that the conversion laws had produced “more headlines than convictions” and overwhelmed the courts. Legislators also acknowledged that many complaints were filed by local vigilante groups or family members under social pressure, not by actual victims.

Interviews with affected individuals further underline a pattern of harassment. One Catholic teacher in Karnataka recalled how an enraged villagers’ mob accused her of “soul-snatching” when she ran a tuition center – even though none of her Hindu students converted. In Madhya Pradesh, a Muslim teenager described being detained for weeks after a matchmaker alleged he had tricked a Hindu girl into marriage. The boy’s family said they were too frightened of retaliation to pursue legal aid. These stories mirror official records: in state assemblies, governments reported dozens of cases each with similar fact patterns, often conceding that evidence was purely testimonial.

Legal experts emphasize that besides prosecutorial zeal, these laws lack procedural safeguards. Many statutes shift the burden of proof onto the accused. A 2025 Rajasthan law explicitly requires anyone changing faith to prove they did so without undue influence. Critics argue this contravenes constitutional rights: the Supreme Court in 1977 held that Article 25 protects voluntary conversion as part of free speech. Yet, by making prosecutions easier and delaying trials, the laws achieve a different goal: “They create a culture of animosity” towards minorities, as USCIRF notes, with discrimination “even when governments are not actively enforcing them”.

Evidence suggests the strategy works politically. In election campaigns, BJP candidates routinely warn Hindu voters about alleged “conversion drives” and promise even tougher measures. Opposition politicians, meanwhile, accuse the government of pandering to extremists. In Uttar Pradesh, for instance, a 2022 police bulletin claimed to uncover a massive Christian “conversion racket” among Dalits, a report that collapsed under judicial scrutiny.

After that episode, an Allahabad High Court judge publicly criticized the state police for bias, implying the conversion law was being misused for minority-scares. Nationally, secular activists warn that the laws fuel divisiveness: as the Asia Director for a leading NGO testified, such laws “stigmatize critics” and invite mob justice. Our research corroborates these claims: in every state we examined, NGOs and legal services report a surge of intimidation complaints coinciding with the passing or enforcement of conversion laws.

Conclusion

Our investigation finds that India’s conversion laws, especially since 2014, have largely been politicized. Despite their stated aim of preventing forced conversions, they overwhelmingly affect those exercising free choice in religion particularly Christians, Muslims, Dalits, and tribal citizens. The laws’ vague language and punitive scope allow for broad application by police and zealots alike.

Official data from state legislatures (e.g. Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh) and civil society indicate thousands of FIRs and arrests but almost no validated cases of coercion. Instead, the main outcome is communal suspicion and legal uncertainty for interfaith families. The laws have become, in effect, a political lever – a way for ruling parties to rally support by projecting protection of Hindus, even as critics call it a betrayal of India’s secular ideals.

Rights groups, clergy and journalists we spoke to emphasize that India’s international image as a democracy is at stake. As one legal scholar put it, the conversion statutes are “designed to regulate religious expression” and have “dubious constitutionality.” Several pending Supreme Court petitions seek to strike down these laws outright as violating fundamental rights. For now, affected communities say they will keep protesting peacefully: as Arunachal’s Bishop Varghese declared on March 6, Indians of all faiths must “stand together for religious harmony,” lest the laws be used to fan divisions.

Citations And References

All citations in this investigation correspond to verified sources gathered during extensive research across multiple continents and databases. Full documentation available upon email to support the accuracy and verifiability of all claims made.

About Our Investigative Services

Seeking to expose corruption, track illicit financial flows, or investigate complex criminal networks? Our specialized investigative journalism agency has proven expertise in following money trails, documenting human rights violations, and revealing the connections between organized crime and corporate malfeasance across the world and beyond.

Partner With Us for Impactful Change

Our investigative expertise and deep industry networks have exposed billion-dollar corruption schemes and influenced policy reform across Americas and beyond.

Whether you’re a government agency seeking independent analysis, a corporation requiring risk assessment and due diligence, or a development organization needing evidence-based research, our team delivers results that matter.

Join our exclusive network of premium subscribers for early access to groundbreaking investigations, or contribute your expertise through our paid contributor program that reaches decision-makers across the continent.

For organizations committed to transparency and reform, we also offer strategic partnership opportunities and targeted advertising placements that align with our mission.

Uncover unparalleled strategic insights by joining our paid contributor program, subscribing to one of our premium plans, advertising with us, or reaching out to discuss how our media relations and agency services can elevate your brand’s presence and impact in the marketplace.

Contact us today to explore how our investigative intelligence can advance your objectives and create lasting impact.

Read all investigative stories About Caste Politics.

* For full transparency, a list of all our sister news brands can be found here.