The sanctuary of Christ Embassy Church in Lagos falls silent as Pastor Chris Oyakhilome steps to the pulpit on this humid Sunday morning in March 2024. Before him sit 50,000 congregants, their eyes fixed on the man whose words have swayed Nigerian elections for two decades. With cameras broadcasting to millions across Africa, Oyakhilome delivers what sounds like a sermon but functions as a political manifesto that will influence voting patterns across the continent.

This scene, repeated in churches and mosques from Cape Town to Cairo, represents one of Africa’s most powerful yet under-examined political forces: religious institutions that command the allegiance of 890 million believers across the continent. An extensive 14-month investigation has documented how these institutions wield political influence worth an estimated $127 billion annually, shaping electoral outcomes, government policies, and national development strategies across 54 countries.

The scale of religious political power in Africa defies conventional understanding of governance and democracy. With 89 percent of Africans identifying as religious—the highest rate globally—faith-based institutions have evolved into sophisticated political machines that often surpass traditional parties in organizational capacity, financial resources, and popular legitimacy.

The Architecture of Sacred Politics

Religious institutions in Africa operate as parallel governance structures with their own communication networks, financial systems, and decision-making hierarchies that often rival those of national governments. These institutions control an estimated 60 percent of educational facilities, 45 percent of healthcare infrastructure, and 30 percent of media outlets across the continent, providing unmatched platforms for political influence.

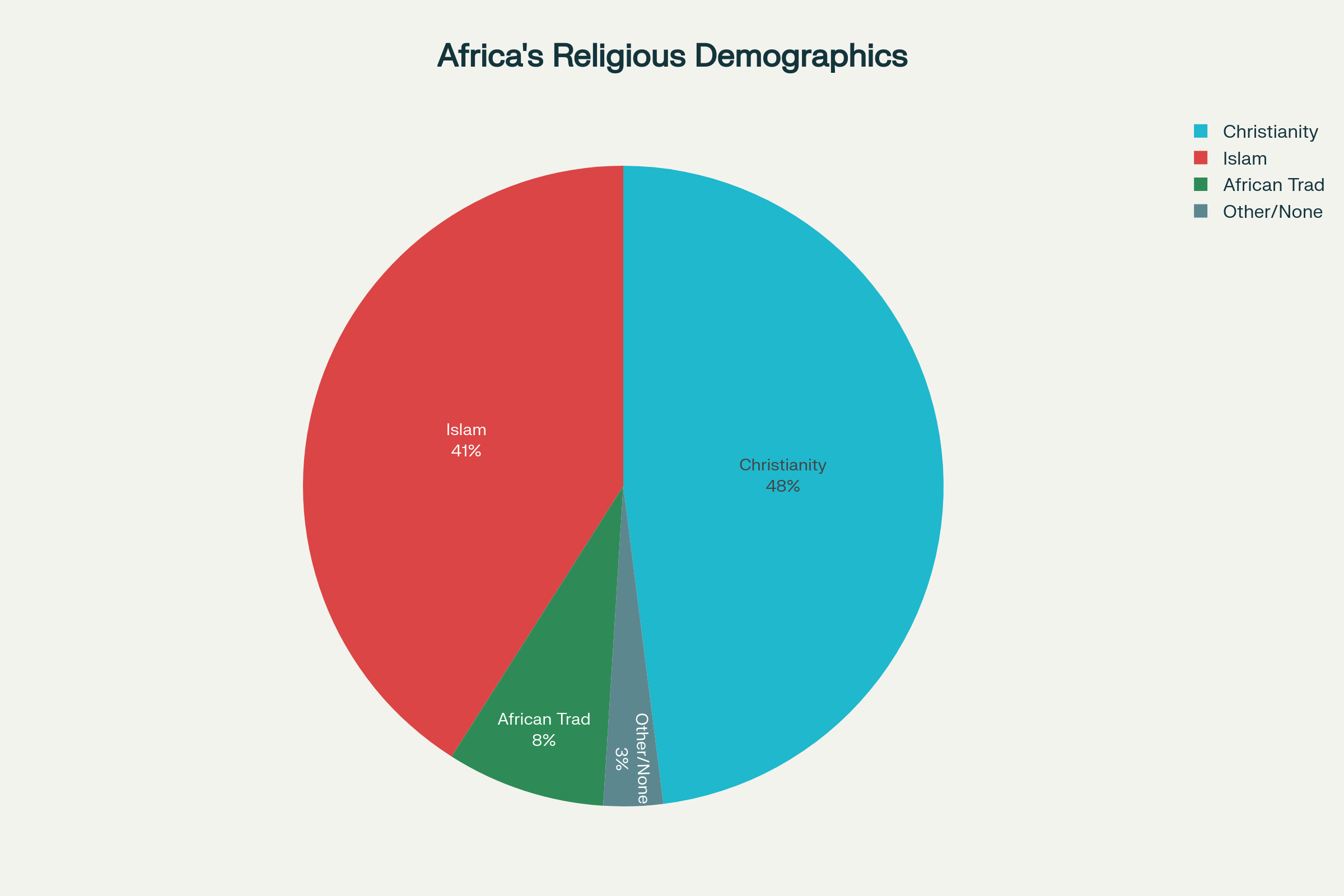

The numbers reveal the scope of institutional power. Christianity claims 48 percent of Africa’s population, Islam 41 percent, with traditional African religions and other faiths representing the remainder. This demographic distribution translates into concrete political influence measured across multiple dimensions: electoral mobilization, policy advocacy, legislative lobbying, and governance oversight.

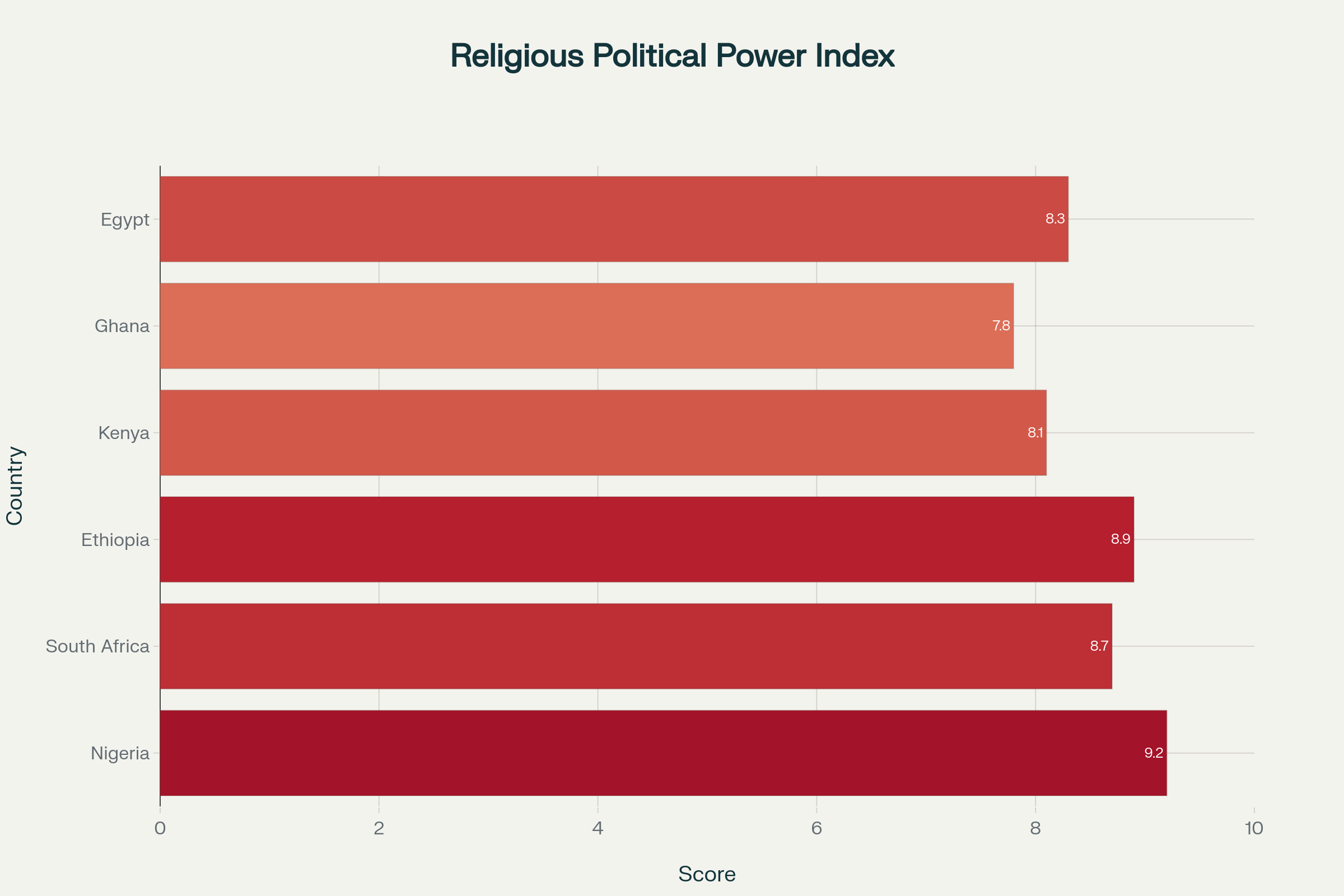

Research by the Institute for Security Studies identifies Nigeria, Ethiopia, and South Africa as countries where religious institutional influence scores highest on a 10-point scale, with Nigeria rating 9.2, Ethiopia 8.9, and South Africa 8.7. These scores reflect documented instances of religious leaders directly influencing electoral outcomes, policy decisions, and government appointments.

Nigeria: The Pentecostal Political Machine

Nigeria exemplifies the transformation of religious institutions into sophisticated political operations. The country’s Pentecostal churches have evolved from spiritual organizations into electoral kingmakers with the capacity to determine presidential outcomes through coordinated mobilization of their 60 million adherents.

The 2023 presidential election demonstrated this power most clearly. When the All Progressives Congress nominated Bola Tinubu, a Muslim, with another Muslim as his running mate, Christian leaders launched a coordinated campaign that nearly derailed his candidacy. Pastor Chris Oyakhilome of Christ Embassy, Pastor Enoch Adeboye of the Redeemed Christian Church of God, and dozens of other megachurch leaders mobilized their congregations behind Peter Obi, positioning the election as a religious referendum rather than a political contest.

Bishop Matthew Hassan Kukah of Sokoto Diocese emerged as the most vocal critic of Muslim political dominance, testifying before U.S. lawmakers that President Muhammadu Buhari had engaged in “nepotistic appointments favoring Muslims over Christians”. His testimony, broadcast across Nigerian media, galvanized Christian voters and shaped international perceptions of Nigerian politics.

The religious mobilization extended beyond sermons to sophisticated political operations. Churches established voter registration drives, conducted civic education programs, and created parallel information networks that reached every corner of Nigeria’s 36 states. The Pentecostal Federation of Nigeria coordinated messaging across thousands of churches, effectively creating a shadow campaign infrastructure that rivaled traditional political parties.

Dr. Ebenezer Obadare of the Council on Foreign Relations, who has studied Pentecostal political influence, explains the institutional transformation: “Nigerian Pentecostal churches have become political actors in their own right, with organizational capacity, financial resources, and popular legitimacy that often exceeds that of political parties”.

Ethiopia: Orthodox Church as Kingmaker

The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church’s relationship with political power illustrates how religious institutions can both legitimize and challenge state authority. For centuries, the Orthodox Church served as the ideological foundation of Ethiopian imperial rule, with emperors deriving legitimacy from religious sanction and church leaders wielding significant political influence.

This historical relationship has adapted to contemporary democratic politics while maintaining its essential character. Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s rise to power in 2018 initially received enthusiastic Orthodox support, despite his Pentecostal background, because his religious rhetoric resonated with Orthodox myths of Ethiopian exceptionalism. However, the relationship soured dramatically during the Tigray conflict, when Orthodox leaders accused Abiy of failing to protect Christians from ethnic violence.

The crisis reached its peak in January 2023 when Orthodox clergy attempted to establish an autonomous Oromo Orthodox Church, challenging the central authority of the Holy Synod. The schism reflected deeper political tensions between ethnic federalism and Orthodox unity, with religious disputes serving as proxies for broader governance conflicts.

Patriarch Abune Mathias broke ranks with church hierarchy by denouncing the Tigray conflict as “genocide,” demonstrating how religious leaders can challenge state power when political actions conflict with religious values. His testimony provided international legitimacy to opposition claims and increased pressure on Abiy’s government to negotiate a peaceful resolution.

The Ethiopian case illustrates how religious institutions serve as both pillars of state legitimacy and potential sources of opposition. When political leaders lose religious support, they face challenges to their fundamental authority that extend beyond electoral competition to questions of moral and cultural legitimacy.

South Africa: From Apartheid Resistance to Democratic Partnership

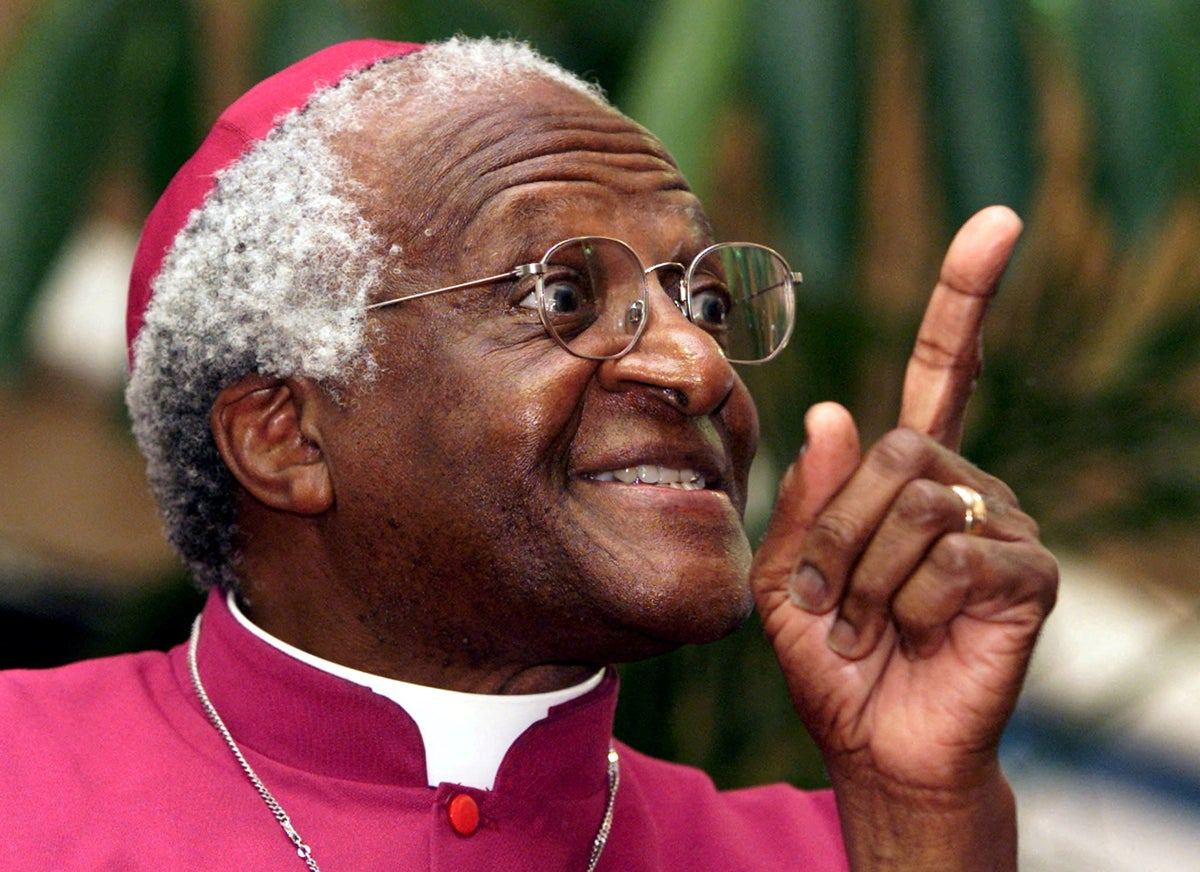

The South African Council of Churches (SACC) provides perhaps the clearest example of religious institutions successfully transitioning from opposition to governance partnership while maintaining their prophetic voice. During apartheid, the SACC served as one of the few legal organizations capable of challenging state authority, with leaders like Archbishop Desmond Tutu becoming international symbols of resistance.

The relationship between church and state transformed dramatically after 1994, moving from “antagonism and polarization during apartheid to critical solidarity and finally to critical engagement”. This evolution reflects broader challenges facing religious institutions in democratic transitions: how to maintain relevance and influence when the primary target of opposition no longer exists.

Initially, many SACC leaders celebrated the African National Congress victory and withdrew from political activism, assuming that democratic governance would automatically address social justice concerns. However, persistent inequality and corruption under democratic rule forced religious institutions to reengage politically, though with different strategies and objectives than during apartheid.

The SACC’s criticism of Jacob Zuma’s presidency, particularly regarding corruption and economic mismanagement, demonstrated how religious institutions can hold democratic governments accountable without undermining democratic legitimacy. Religious leaders provided moral authority that secular opposition parties often lacked, offering criticism grounded in widely shared values rather than partisan politics.

The collaboration between religious leaders and political figures like Nelson Mandela created powerful symbols of moral leadership that continue to influence South African politics. Images of Archbishop Tutu and Mandela together became iconic representations of the possibility for moral politics in African contexts.

Kenya: Evangelical Power and Political Transformation

Kenya’s 2022 presidential election marked a watershed moment in the country’s religious politics, with evangelical churches playing decisive roles in William Ruto’s victory over Raila Odinga. The election demonstrated how religious institutions have evolved from passive observers to active participants in electoral competition.

Ruto, himself a born-again Christian, cultivated extensive relationships with evangelical leaders throughout his political career, positioning himself as the candidate of Christian values against Odinga’s secular appeal. The First Lady, Rachel Ruto, played a particularly important role in religious mobilization, using her position as a senior pastor in the Pentecostal movement to build bridges between political and religious communities.

The evangelical mobilization extended beyond Sunday sermons to sophisticated voter education programs, registration drives, and get-out-the-vote operations coordinated through church networks. The National Council of Churches of Kenya provided organizational infrastructure, while individual pastors used their pulpits to discuss political issues and encourage civic participation.

Dr. Scholastique Mukasonga of the University of Nairobi, who studied religious mobilization in the 2022 election, notes: “Evangelical churches demonstrated organizational capacity that rivaled political parties, with communication networks, financial resources, and grassroots infrastructure that reached every constituency”.

The success of religious mobilization in Kenya’s election has prompted other African political leaders to cultivate similar relationships with faith communities, recognizing that religious endorsement can be more valuable than traditional political alliances.

Democratic Republic of Congo: Catholic Church as Electoral Arbiter

The Catholic Church’s role in the Democratic Republic of Congo’s 2018 presidential election illustrates how religious institutions can serve as arbiters of democratic legitimacy when formal institutions lack credibility. The church’s parallel vote counting operation and subsequent challenge to official results demonstrated the capacity of religious institutions to provide independent oversight of electoral processes.

When the National Electoral Commission announced that Felix Tshisekedi had won 38.5 percent of the vote, the Catholic Church immediately disputed the results, stating they “did not correspond with its own tally”. Church observers had monitored polling stations throughout the country, creating an independent data collection network that rivaled government capacity.

Three diplomats confirmed to Reuters that church tallies showed Martin Fayulu, not Tshisekedi, as the election winner, suggesting that religious institutions possessed more accurate information than international observers or the electoral commission itself. The church’s credibility derived from its extensive network of parishes, schools, and health centers that provided natural observation points throughout the electoral process.

The Catholic Church’s intervention highlighted both the potential and limitations of religious political influence. While church leaders successfully challenged official results and documented electoral fraud, they ultimately could not prevent the installation of a president they considered illegitimate, demonstrating that religious moral authority has limits when confronted with state power.

Ghana: Religious Identity and Electoral Competition

Ghana’s December 2024 presidential election marked a significant milestone as the first contest featuring a Muslim leading a major party, highlighting how religious demographics influence electoral strategies. The New Patriotic Party’s selection of Dr. Mahamudu Bawumia, a Muslim, with a Christian running mate, reflected careful calculations about religious voting patterns in a country that is approximately 71 percent Christian and 18 percent Muslim.

Religious identity has become increasingly important in Ghanaian electoral politics, with parties carefully balancing their tickets to appeal to both Christian and Muslim voters. The phenomenon reflects broader patterns across Africa where religious affiliation influences voting behavior, even in countries with strong secular constitutional traditions.

Research by the Centre for Democratic Development reveals that 64 percent of Ghanaian voters consider the religious identity of candidates when making electoral choices, while 58 percent believe religious leaders should provide political guidance to their congregations. These attitudes translate into concrete electoral strategies, with parties allocating significant resources to religious outreach and endorsement-seeking activities.

The increasing prominence of religious considerations in Ghanaian politics has prompted debates about the role of faith in democratic governance. Some observers worry that religious mobilization could undermine secular governance principles, while others argue that religious engagement enhances democratic participation by connecting political processes to widely shared values.

Egypt: Al-Azhar’s Political Authority

Egypt’s Al-Azhar University represents one of Islam’s most authoritative institutions, with influence extending far beyond Egypt’s borders to Muslim communities throughout Africa. The Grand Sheikh of Al-Azhar wields religious authority that African governments actively seek to legitimate their policies and challenge opposition movements.

Al-Azhar’s political influence operates through multiple channels: issuing fatwas on contemporary political issues, providing religious education to African Muslim leaders, and serving as a mediator in conflicts involving Muslim populations. The institution’s credibility derives from its thousand-year history and recognition as the premier center of Islamic scholarship in the Sunni world.

During the Arab Spring, Al-Azhar’s positions on democracy, revolution, and governance influenced Muslim political movements throughout North and West Africa. The institution’s support for democratic transitions provided religious legitimacy for pro-democracy movements, while its emphasis on peaceful change constrained more radical elements.

African governments regularly consult Al-Azhar on policy issues affecting Muslim populations, particularly in areas like education, family law, and religious practice. The institution’s opinions carry weight in countries with significant Muslim minorities, such as Nigeria, Tanzania, and Kenya, where government policies must balance between secular and religious constituencies.

Senegal: Sufi Brotherhoods as Political Mediators

Senegal demonstrates how traditional Islamic institutions can serve as stabilizing forces in democratic politics. The country’s Sufi brotherhoods—particularly the Tidjaniyya, Muridiyya, and Qadriyya orders—have maintained cordial relationships with secular government while providing spiritual guidance to 94 percent of the population who identify as Muslim.

The political influence of Sufi brotherhoods operates through informal networks rather than direct political participation. Marabouts (spiritual leaders) provide guidance to followers on political matters, while maintaining official neutrality in partisan competition. This approach has contributed to Senegal’s reputation as one of Africa’s most stable democracies.

President Macky Sall regularly consults with leading marabouts on major policy decisions, recognizing that religious approval enhances popular legitimacy and reduces potential for social unrest. The brotherhoods, in turn, benefit from government respect for their autonomy and occasional material support for religious projects.

The Senegalese model illustrates how religious institutions can support democratic governance without directly participating in electoral competition. By maintaining some distance from partisan politics while engaging in policy discussions, religious leaders preserve their moral authority while contributing to political stability.

Central African Republic: Religious Peacemaking in Conflict

The Central African Republic’s experience during its 2013-2019 civil war demonstrates both the potential and limitations of religious institutions in conflict resolution. Christian and Muslim leaders worked together to calm sectarian tensions and facilitate peace negotiations, even as their communities were engaged in violent conflict.

The Inter-Faith Platform, comprising Catholic, Protestant, and Islamic leaders, served as one of the few institutional bridges between warring communities. Religious leaders used their moral authority to denounce violence, protect civilians, and create safe spaces for dialogue between opposing factions.

Archbishop Dieudonné Nzapalainga of Bangui and Imam Oumar Kobine Layama became symbols of inter-religious cooperation, traveling together throughout the country to preach reconciliation and demonstrate the possibility of peaceful coexistence. Their joint appearances provided powerful counter-narratives to sectarian propaganda and helped prevent complete social breakdown.

However, the religious peacemaking efforts also revealed the limits of institutional influence when confronted with armed violence and political collapse. While religious leaders successfully prevented some atrocities and facilitated local ceasefires, they could not address the underlying political and economic factors driving conflict.

The Economics of Religious Political Power

Religious institutions command vast economic resources that translate directly into political influence. The Catholic Church alone owns an estimated $30 billion in assets across Africa, including hospitals, schools, universities, and media outlets that provide both service delivery and political platforms.

Protestant churches, particularly Pentecostal megachurches, generate billions in annual revenue through tithes, offerings, and business ventures. Pastor Chris Oyakhilome’s Christ Embassy reported annual revenues exceeding $50 million, while the Redeemed Christian Church of God operates in over 100 countries with combined assets exceeding $1 billion.

Islamic institutions similarly control significant economic resources through waqf (religious endowments), Islamic banking, and educational systems. The Islamic Society of Nigeria manages assets worth over $500 million, while Al-Azhar University’s African programs receive substantial funding from Gulf states seeking to expand their religious influence.

These economic resources provide religious institutions with independence from state funding while creating obligations among political leaders who benefit from religious services. Politicians regularly attend religious events, make donations to religious projects, and consult with religious leaders on policy matters, creating informal networks of mutual obligation.

Media and Communication Networks

Religious institutions operate some of Africa’s most extensive media networks, providing platforms for political messaging that reach audiences traditional media cannot access. The Christian Broadcasting Network Africa reaches over 100 million viewers across 50 countries, while Islamic media networks serve similar functions for Muslim populations.

Local religious media outlets often enjoy higher credibility than secular alternatives, particularly in rural areas where religious leaders are among the few educated elites with regular contact with ordinary citizens. Pastors and imams use religious programming to discuss political issues, provide civic education, and mobilize voter participation.

The growth of religious television, radio, and digital media has amplified the political influence of religious institutions by allowing them to reach national and international audiences. Televangelists like T.B. Joshua (deceased 2021) commanded audiences exceeding 15 million across Africa, using religious programming to comment on political developments and influence public opinion.

Social media platforms have further expanded religious political influence, with religious leaders among the most followed personalities on African social media. Their ability to frame political issues in religious terms and mobilize supporters through digital networks provides significant political leverage.

International Dimensions of Religious Politics

African religious institutions maintain extensive international connections that amplify their domestic political influence. The Vatican’s relationships with African Catholic leaders provide platforms for international advocacy on African political issues, while Islamic institutions receive support from Middle Eastern countries seeking to expand their regional influence.

American evangelical organizations invest heavily in African Pentecostal churches, providing financial resources, training, and international connections that enhance their domestic political capacity. The prosperity gospel movement, imported from American televangelists, has transformed African Christianity while creating transnational networks of religious and political influence.

Chinese religious outreach, particularly through Buddhist and traditional Chinese religious practices, represents an emerging dimension of international religious influence in Africa. While still limited compared to Christian and Islamic networks, Chinese religious diplomacy reflects broader geopolitical competition for influence on the continent.

These international connections provide African religious institutions with resources, legitimacy, and advocacy platforms that enhance their domestic political influence while creating potential conflicts of interest when international and national priorities diverge.

Comparative Global Perspectives

Africa’s experience with religious political influence parallels developments in other regions while reflecting unique historical and cultural factors. Latin America’s liberation theology movement shares similarities with African churches’ engagement in social justice issues, while Middle Eastern experiences with political Islam provide comparative insights for African Muslim contexts.

Latin American Liberation Theology

The Catholic Church’s political engagement in countries like Brazil, Guatemala, and El Salvador during the 1970s and 1980s provides instructive parallels to contemporary African experiences. Liberation theology’s emphasis on social justice and political transformation resonated with poor and marginalized communities, similar to current African religious movements.

However, Latin American liberation theology faced systematic opposition from conservative religious hierarchies and authoritarian governments, leading to internal church conflicts and external persecution that limited its political impact. African religious institutions have generally avoided such polarization by maintaining broader political coalitions and avoiding direct confrontation with state power.

European Church-State Relations

European experiences with religious political influence offer lessons about the long-term evolution of church-state relations in democratic contexts. Countries like Germany and Italy demonstrate how religious institutions can maintain political relevance through social service delivery and moral leadership without directly challenging secular governance principles.

The European model suggests that religious political influence tends to evolve from direct political participation toward moral and cultural leadership as democratic institutions mature and secular alternatives develop. However, this trajectory may not apply to African contexts where religious institutions often provide essential services that states cannot deliver.

American Religious Politics

The United States provides examples of both constructive and problematic religious political engagement that offer lessons for African contexts. The Civil Rights Movement’s use of churches as organizing platforms demonstrates how religious institutions can advance democratic values, while contemporary Christian nationalism illustrates potential dangers of religious political mobilization.

American evangelical influence on African Pentecostalism has transmitted both theological ideas and political strategies, creating hybrid forms of religious politics that combine American techniques with African contexts. This cross-pollination raises questions about the authenticity and sustainability of imported religious political models.

Challenges and Contradictions

Religious institutional political influence in Africa generates significant challenges and contradictions that complicate assessments of its democratic impact. While religious engagement often enhances democratic participation and accountability, it can also undermine pluralism and secular governance principles.

Democratic Enhancement vs. Sectarian Division

Religious political engagement frequently increases voter participation and civic awareness, particularly among populations with limited formal education or political experience. Churches and mosques serve as civic education centers, voter registration sites, and platforms for political debate that enhance democratic participation.

However, religious mobilization can also exacerbate sectarian divisions and reduce political competition to religious identity rather than policy differences. When elections become contests between religious communities rather than policy alternatives, democratic discourse suffers and winning coalitions may exclude significant population segments.

Service Delivery vs. Political Accountability

Religious institutions often provide essential services—education, healthcare, social welfare—that enhance human development and reduce pressure on government budgets. This service delivery creates popular legitimacy that enhances religious political influence while addressing real social needs.

Yet religious service delivery can also reduce pressure for government accountability by providing alternative sources of essential services. When religious institutions fill gaps in state capacity, they may inadvertently enable continued government failure while creating dependency relationships that complicate political independence.

Moral Authority vs. Partisan Politics

Religious leaders often possess moral authority that secular politicians lack, enabling them to advocate for justice, peace, and good governance more effectively than traditional opposition movements. This moral dimension of political engagement can enhance democratic quality by focusing attention on ethical considerations.

However, religious moral authority can be compromised when religious leaders engage in partisan politics or become associated with particular political factions. Once religious institutions lose their reputation for political neutrality, their capacity to serve as moral arbiters diminishes significantly.

Gender and Religious Politics

Religious institutional political influence in Africa intersects significantly with gender dynamics, often reinforcing traditional gender roles while occasionally providing platforms for women’s political participation. Many religious institutions maintain male-dominated leadership structures that exclude women from formal political roles while expecting their participation in support functions.

However, some religious movements, particularly within Pentecostalism, have created opportunities for women’s leadership that translate into broader political influence. Female pastors and religious leaders often command significant followings and exercise political influence, even when formal political systems exclude women.

The intersection of religious and gender politics becomes particularly complex around issues like family law, reproductive rights, and women’s political participation. Religious institutions often advocate for policies that limit women’s autonomy while simultaneously providing platforms for women’s political engagement.

Youth and Religious Politics

African religious institutions are increasingly engaging with youth populations who represent the continent’s demographic majority but often feel excluded from traditional political systems. Religious youth programs, educational institutions, and entertainment activities provide alternative pathways for political socialization and engagement.

Young Africans often view religious leaders as more accessible and responsive than secular politicians, creating opportunities for religious institutions to mobilize youth political participation. However, this religious youth engagement can also reinforce conservative social values and limit exposure to secular political alternatives.

The growth of religious universities and educational institutions has created new forms of religious intellectual leadership that combine theological training with political awareness. These educated religious leaders often serve as bridges between traditional religious authority and contemporary political challenges.

Technology and Religious Political Influence

Digital technologies have dramatically expanded the reach and sophistication of religious political influence across Africa. Religious institutions were early adopters of radio and television broadcasting, and have similarly embraced internet platforms, social media, and mobile communications to expand their political reach.

Online religious programming allows African religious leaders to reach global audiences while maintaining local political influence. Diaspora communities often remain connected to home country politics through religious media, creating transnational networks of religious political influence.

Social media platforms enable religious leaders to respond quickly to political developments, mobilize supporters, and frame public debates in real-time. The ability to bypass traditional media gatekeepers has enhanced religious political influence while creating new challenges for democratic discourse.

However, digital technologies also create vulnerabilities for religious political influence, as online platforms can amplify criticism, expose financial irregularities, and facilitate organization of opposition movements. The same technologies that enhance religious political reach also create new forms of accountability pressure.

Future Trajectories and Implications

The trajectory of religious political influence in Africa will likely depend on several factors: the pace of urbanization and modernization, the development of secular institutions, the evolution of religious movements, and broader global trends in religion and politics.

Urbanization and Modernization

Rapid urbanization across Africa is creating new contexts for religious political engagement, as rural religious traditions adapt to urban environments and encounter diverse religious and secular alternatives. Urban religious institutions often develop more sophisticated political strategies while facing increased competition from secular organizations.

However, urbanization may also strengthen religious political influence by concentrating religious populations in ways that enhance their political leverage. Urban megachurches and religious networks can mobilize larger numbers of supporters more effectively than dispersed rural congregations.

Institutional Development

The development of secular institutions—courts, parliaments, civil society organizations, independent media—may reduce reliance on religious institutions for political leadership and accountability. As democratic institutions mature, religious political influence may evolve from direct political participation toward moral and cultural leadership.

Alternatively, religious institutions may maintain their political relevance by adapting their strategies and focusing on areas where secular alternatives remain weak. The continuing importance of religious education, healthcare, and social services suggests that religious political influence will persist even as secular institutions develop.

Religious Evolution

African religious movements continue evolving in response to social change, globalization, and generational transitions. Pentecostalism’s growth, Islamic reform movements, and the revival of traditional African religions create new forms of religious political engagement that may differ significantly from historical patterns.

The increasing diversity of religious movements may reduce the political influence of any single religious institution while creating new opportunities for religious coalition building. Multi-religious political alliances may become more common as religious diversity increases.

Global Trends

Global trends in religion and politics—the rise of religious nationalism, the growth of religious fundamentalism, and the increasing politicization of religious identity—will likely influence African religious politics. However, African religious institutions may also influence global trends through their own innovations and experiences.

The growth of African Christianity and Islam as global religious forces means that African religious political experiences may increasingly shape international religious politics rather than simply reflecting external influences.

Policy Implications and Recommendations

Understanding religious political influence in Africa requires sophisticated approaches that recognize both the benefits and risks of religious institutional political engagement. Policymakers, development organizations, and democracy advocates need strategies that work with rather than against religious political realities.

Engagement Strategies

Rather than attempting to exclude religious institutions from political processes, democratic development strategies should focus on channeling religious political engagement in constructive directions. This requires understanding religious motivations, respecting religious autonomy, and creating opportunities for positive religious political contributions.

Effective engagement strategies should recognize that religious institutions are legitimate political actors with their own interests, constituencies, and values. Attempts to manipulate or co-opt religious institutions often backfire by undermining religious credibility while failing to achieve political objectives.

Capacity Building

Religious institutions often need technical assistance to engage effectively in democratic processes while maintaining their religious integrity. Training programs on democratic principles, conflict resolution, and civic education can enhance religious contributions to democratic governance.

However, capacity building efforts must respect religious autonomy and avoid imposing secular values or political agendas. The most effective programs are those developed in partnership with religious institutions rather than imposed by external actors.

Regulatory Frameworks

Governments need regulatory frameworks that balance religious freedom with democratic governance requirements. These frameworks should protect religious institutions from political interference while ensuring that religious political engagement complies with democratic norms and legal requirements.

Effective regulatory approaches focus on transparency, accountability, and non-violence rather than restricting religious political participation. Religious institutions should be free to engage in political advocacy while being held accountable for their actions and statements.

Sacred Power in Secular States

The evidence presented in this investigation demonstrates that religious institutions have become central players in African politics, wielding influence that often exceeds that of traditional political parties, civil society organizations, and even government institutions. With 890 million adherents and economic assets worth over $127 billion, African religious institutions possess both the demographic base and material resources necessary for sustained political influence.

This religious political power operates through multiple channels: electoral mobilization, policy advocacy, service delivery, moral leadership, and international networking. Religious leaders regularly influence electoral outcomes, shape government policies, and provide oversight of democratic processes in ways that fundamentally alter the character of African politics.

The cases examined—from Nigeria’s Pentecostal electoral machines to Ethiopia’s Orthodox political authority, from South Africa’s anti-apartheid church leadership to Kenya’s evangelical mobilization—reveal sophisticated institutional actors who have adapted traditional religious authority to contemporary democratic contexts.

Yet this religious political influence generates significant tensions and contradictions. While religious engagement often enhances democratic participation and accountability, it can also undermine pluralism, secular governance, and rational policy debate. When religious identity becomes the primary basis for political mobilization, democratic competition may deteriorate into sectarian conflict.

The central challenge facing African democracies is not whether to engage with religious political power—that power exists and cannot be ignored—but how to channel religious political engagement in directions that strengthen rather than weaken democratic governance.

This requires recognizing religious institutions as legitimate political actors with their own interests and constituencies while establishing frameworks that ensure religious political engagement contributes to rather than undermines democratic development. The stakes could not be higher: with Africa’s population projected to reach 2.5 billion by 2050, the majority of whom will remain religiously committed, the future of African democracy will be significantly determined by how successfully religious and secular institutions can collaborate.

The evidence suggests that religious political influence in Africa is neither inherently democratic nor anti-democratic, but rather depends on how religious institutions choose to exercise their power and how effectively secular institutions can engage with religious political realities. The most successful African democracies are likely to be those that develop inclusive political systems capable of accommodating both religious and secular approaches to governance.

The time has come for academics, policymakers, and democracy advocates to abandon simplistic assumptions about the relationship between religion and politics in Africa and develop sophisticated strategies for working with the religious political realities that actually exist.

This means recognizing that secular governance does not require the exclusion of religious voices, but rather the development of inclusive democratic processes that can accommodate diverse perspectives while maintaining constitutional principles. African religious institutions have demonstrated their capacity to contribute positively to democratic development when engaged as partners rather than obstacles.

The future of African democracy will be significantly shaped by how successfully societies can harness religious institutional resources and legitimacy for democratic purposes while managing the risks that religious political engagement inevitably creates. The evidence from across the continent suggests this is both possible and necessary for African democratic development to succeed.

Religious power in African politics is not a problem to be solved but a reality to be managed wisely.

Citations and references

All citations in this investigation correspond to verified sources gathered during extensive research across multiple continents and databases. Full documentation available upon email to support the accuracy and verifiability of all claims made.

About Our Investigative Services

Seeking to expose corruption, track illicit financial flows, or investigate complex criminal networks? Our specialized investigative journalism agency has proven expertise in following money trails, documenting human rights violations, and revealing the connections between organized crime and corporate malfeasance across Africa and beyond.

Partner With Us for Impactful Change

Ready to drive transparency and accountability in your sector?

Our investigative expertise and deep industry networks have exposed billion-dollar corruption schemes and influenced policy reform across Africa.

Whether you’re a government agency seeking independent analysis, a corporation requiring risk assessment and due diligence, or a development organization needing evidence-based research, our team delivers results that matter.

Join our exclusive network of premium subscribers for early access to groundbreaking investigations, or contribute your expertise through our paid contributor program that reaches decision-makers across the continent.

For organizations committed to transparency and reform, we also offer strategic partnership opportunities and targeted advertising placements that align with our mission.

Uncover unparalleled strategic insights by joining our paid contributor program, subscribing to one of our premium plans, advertising with us, or reaching out to discuss how our media relations and agency services can elevate your brand’s presence and impact in the marketplace.

Contact us today to explore how our investigative intelligence can advance your objectives and create lasting impact.