Global fast‑fashion brands pride themselves on speed and style, but hidden behind their glossy storefronts is the grim reality of supply chain slavery. The clothes that fill shopping carts and closets are often stitched together by workers trapped in conditions that human rights groups describe as modern slavery.

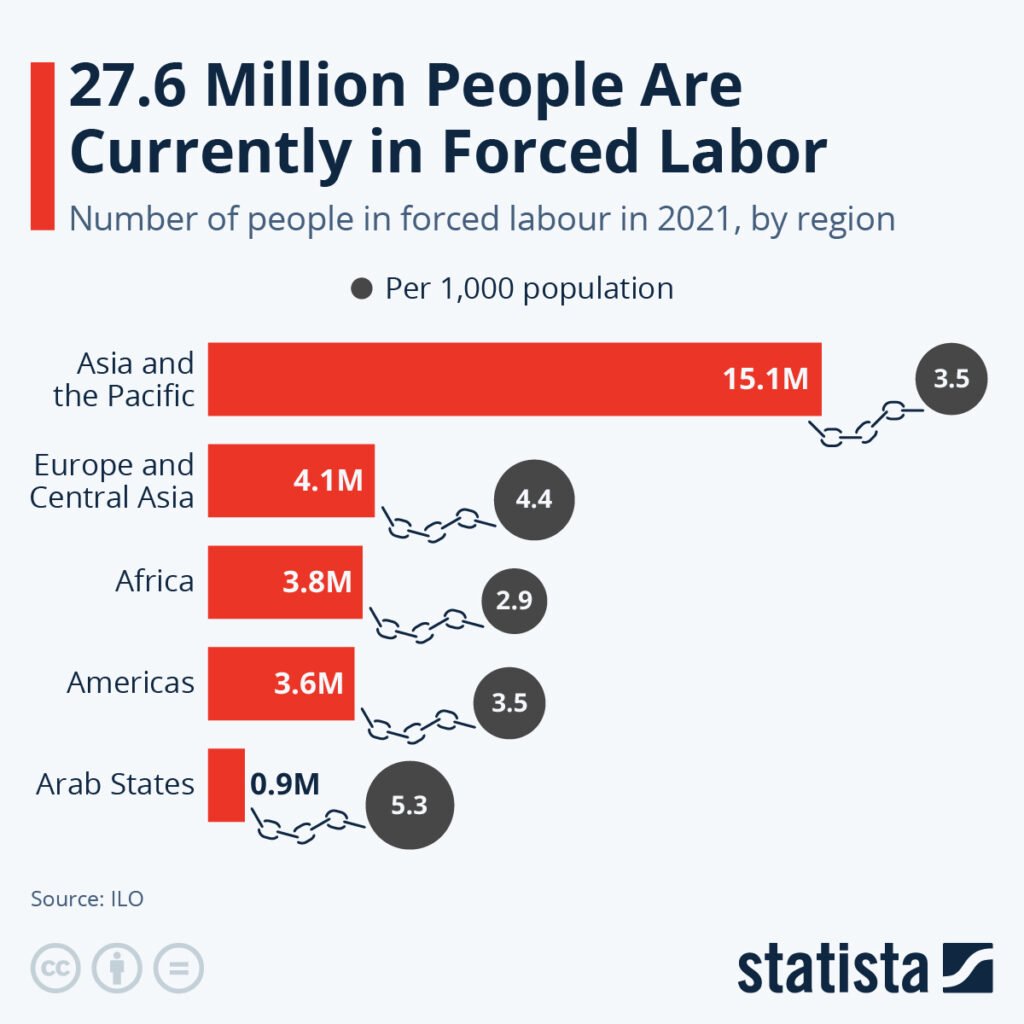

The International Labour Organisation estimates that 27.6 million people are held in forced labour worldwide, including 17.3 million exploited in the private economy and 3.9 million subjected to state‑imposed forced labour.

Modern slavery taints every stage of the global apparel supply chain—from cotton fields and spinning mills to garment factories and shipping ports. This investigative report draws on testimonies from workers, civil society reports and legal experts to expose how exploitation persists across continents and to examine the regulatory attempts to tackle it.

Mapping the Apparel Supply Chain

Before exploring specific regions, it is important to understand how garments travel from raw materials to store shelves. A typical cotton T‑shirt may start in fields where farmers harvest and gin cotton, then move to mills where fibres are spun into yarn and woven into fabric.

The fabric is then cut and sewn in garment factories often by subcontractors before being transported by sea, rail or road to distribution centres and retailers. Each link in this chain is an opportunity for exploitation.

Anti‑Slavery International warns that slavery can exist in every stage of the supply chain, from the extraction of raw materials to manufacturing and shipping. Complex multi‑tier supplier networks make it difficult to trace components back to a specific farm or mill, allowing abuses to remain hidden.

Raw Materials: Cotton Cultivation and Forced Labour

Xinjiang and State‑Imposed Forced Labour in China

Much of the world’s cotton originates in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of China. Since 2016, the Chinese government has detained hundreds of thousands of Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities in “re‑education” camps where they are subjected to indoctrination, surveillance and forced labour. Survivors describe producing textiles in factories with little or no pay and no freedom to leave.

Even outside Xinjiang, labour transfer programs relocate Uyghur workers to factories across China, where they are segregated, their movements monitored and their identification documents confiscated. In 2022 alone, more than three million Uyghurs were transferred to other parts of the country under these programmes. Products made by the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps—a state‑run conglomerate that oversees much of the region’s cotton, yarn and garment production—are exported worldwide and have been sanctioned by the United States for human rights abuses.

The prevalence of Xinjiang cotton in global supply chains cannot be overstated. Anti‑Slavery International estimates that almost 20 % of the world’s cotton supply is linked to China’s forced labour of Uyghurs and other Turkic and Muslim groups, meaning that nearly every high‑street brand could be tainted. Because cotton fibres from various sources are mixed during spinning and fabric production, it is nearly impossible for companies to guarantee that a garment is free of Xinjiang cotton without rigorous traceability systems.

Cotton Farming in India and Pakistan

Forced labour does not occur only in China. In southern India, thousands of young women and girls have been trapped in the Sumangali scheme, where they are recruited for three‑year contracts in spinning mills with promises of a lump‑sum payment at the end. Many start work at 13 or 14 years old and are cut off from their families while living in factory hostels. Civil society groups estimate that around 120,000 workers were involved in the scheme at its peak.

Cash advances, withheld wages and debt bondage tie them to employers, and investigators have rescued boys and adult men trafficked from other Indian states to work without pay. Despite initiatives that have identified and rehabilitated over 35,000 survivors, the scheme persists under new names and the underlying economic pressures remain unaddressed.

Pakistan’s cotton farms also reveal troubling practices. A 2021 survey found that 27 % of cotton farm workers reported not being able to leave work and 20 % saw children under 15 working on farms, indicating coerced labour and child exploitation. Many farmers work through labour contractors and face wage deductions, debts and piece‑rate pay that make it impossible to earn a living. When the COVID‑19 pandemic struck and global demand plummeted, some brands cancelled orders and refused to pay for completed goods, pushing farmers and workers further into debt.

Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan

Although there has been progress in recent years, forced labour in cotton cultivation also remains endemic in Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan. State‑sponsored recruitment drives have historically conscripted millions of citizens to pick cotton under threat of penalties. Thanks to international pressure and domestic reforms, Uzbekistan officially ended mass mobilisations in 2022, but reports of coercion continue, particularly in Turkmenistan. These cases highlight how state‑imposed systems can embed forced labour deep into global textiles.

Manufacturing: Behind the Factory Walls

Bangladesh: Long Hours, Low Pay and Union Suppression

Bangladesh is the world’s second‑largest garment exporter, employing over four million workers. While low wages attracted brands after the Multi‑Fibre Arrangement ended, they have also locked workers into poverty. Even after the national minimum wage was increased to 12,500 taka (≈€94) per month, Bangladeshi garment workers earn only around 38 % of a living wage, forcing them to rely on overtime or loans to meet basic needs.

In a briefing by Swedwatch, a female worker named Shapna explains that without overtime she must take loans continuously to survive. Weak labour law enforcement and barriers to unionisation leave workers with little bargaining power, while brands engage in “price squeezing” and shorter deadlines that push suppliers to cut wages and extend working hours.

The Rana Plaza disaster of April 2013 remains a stark symbol of these pressures. Factory owners ordered workers back into an eight‑storey building despite visible structural cracks. When the building collapsed, 1,134 people were killed and thousands were injured. Survivors recall being forced to choose between death and unemployment, with some amputating limbs to free themselves from the rubble.

The tragedy spurred global outrage and safety reforms, but conditions remain perilous. The GoodWeave/Nottingham study shows that 97.3 % of factories require overtime and that workers in subcontracted factories face frequent payment delays and wage withholding.

More than 64 % of workers feel pressured to work more than eight hours because of production targets or fear of losing their jobs. Cash payments are common (72 % of workers in subcontracted factories are paid in cash), making wages less transparent and easier to manipulate.

Union repression compounds these abuses. A Bangladeshi trade unionist, Nazma Akter, told reporters in 2023 that due to reduced orders, factories require overtime to meet deadlines and there are concerns about paying wages. She described how workers are coerced into overtime and face harassment when they protest. The lack of credible unions means that wage increases and safety improvements rely largely on international pressure.

India: The Sumangali Scheme and Spinning‑Mill Slavery

India’s textile industry employs around 45 million workers, making it the world’s second‑largest textile producer. Yet, hidden within Tamil Nadu’s spinning mills is a system of bonded labour known as Sumangali. Girls aged between 13 and 18 are recruited through advertisements promising a dowry at the end of a three‑year contract.

They leave their villages believing they will earn money for marriage but instead face isolation, excessive overtime, restricted movement and sometimes sexual violence. Transparentem’s investigation found that recruitment agents withheld identity documents and used threats to prevent escape, while factory owners restricted contact with families.

Local civil society groups estimate that around 100,000 workers remain trapped in modern slavery conditions in Tamil Nadu’s mills. The scheme persists under different names like Camp Coolie, Thirumagal Thirumana, Mangalam and is difficult to eradicate because families are poor and local job opportunities are scarce. In the power‑loom sector, cash advances and low piece‑rate wages bind workers to employers. Transparentem also documented child labour and unsafe conditions on cotton farms in Madhya Pradesh, engaging 60 buyers to remediate abuses.

Pakistan: Contract Labour, Debt and “Amazon” Factories

Pakistan exports billions of dollars of apparel annually, yet many garment workers remain informal and unprotected. A 2025 summary of Arisa’s report on Pakistan’s garment sector found that 20‑30 % of workers are hired through contractors, and 31 % had not signed a contract while 62 % did not receive a copy. Forty percent of workers reported 13–22 hours of overtime per week, and 3 % worked more than 23 hours often exceeding 71 hours in total.

Sixty‑five percent could not refuse overtime without harassment or threats. Many were paid below the legal minimum wage, faced deductions for being late or taking food breaks, and were laid off to avoid paying bonuses. There are no independent unions or collective bargaining agreements, and 70 % of workers do not even know what a union is.

Debt traps further entrench forced labour. Forty‑one percent of Pakistani workers are in debt, with some receiving employer advances that lock them into their jobs. Social security coverage is rare, 78 % are not registered for health care or pensions and factories sometimes close abruptly without paying severance. In a separate investigation, the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre (BHRRC) traced shipments from three Pakistani factories supplying Amazon sellers and found that workers were not paid minimum wages, had no contracts or payslips, worked excessive hours and were excluded from social security.

A machinist named Hussain described working a ten‑hour day for about 35,700 Pakistani rupees (≈US$125) per month, while the brands selling his garments in the United States charged hundreds of dollars per item. Amazon responded that its sellers must comply with supply chain standards but provided little transparency.

Vietnam: Fast Fashion Pressure and Legal Pressures

Vietnam has become a major hub for fast‑fashion manufacturing, boasting high productivity and favourable trade agreements. Yet, workers face growing exploitation. A 2024 investigation by the Human Rights Research Centre found that foreign investors are under pressure to cut costs and maintain profits, leading employers to reduce wages and impose longer hours.

Minimum wages which are about 4,680,000 VND (≈US$200) per month in major cities do not cover the cost of rent and food, forcing many workers to log over 50 hours of overtime a month. Those who request less overtime risk dismissal. The article notes that despite earning more than double the minimum wage, some workers still cannot meet basic necessities and are trapped in a cycle of exploitation. Brands demand low prices, large orders and unrealistic deadlines, causing factories to squeeze labour costs and cut corners.

Legal developments outside Vietnam are shaping its apparel industry. The U.S. Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA), enacted in 2021 and effective in 2022, bans goods with any component from Xinjiang or from blacklisted entities, imposing a rebuttable presumption that products from the region are made with forced labour. To import goods into the United States, companies must prove that their supply chains are free of forced labour. Because many Vietnamese garment factories are owned by Chinese companies reliant on Xinjiang cotton, UFLPA has disrupted supply chains and forced some factories to re‑source materials. EU legislation discussed later will require similar due diligence.

Myanmar: Coups, Coercion and Brand Complicity

After Myanmar’s military coup in February 2021, labour rights deteriorated drastically. IndustriALL reports that garment workers are forced to work overtime without compensation, face wage arrears, and see production targets increased to unrealistic levels. Minors are illegally hired, and those who refuse overtime are fired.

At the Wonderful Apparel factory, workers were paid only 10,000 kyat (≈US$4.70) per day and were required to work through the night. When workers at the Charis Sculpture factory went on strike demanding decent wages, several were assaulted and dismissed. The ILO’s indicators of forced labour including abuse of vulnerability, deception, physical violence, intimidation, withholding wages and excessive overtime are present. The ILO suspended Myanmar from its governing body meetings, signalling international condemnation.

Labour leaders urge brands to divest from Myanmar. Atle Høie, general secretary of IndustriALL, argues that brands continuing to operate in Myanmar profit from forced labour and cannot ensure due diligence under military rule. Despite this, several European brands, including Next, New Yorker and LPP, continue sourcing from Myanmar. Workers lack avenues to challenge exploitation, and wages are deducted for taking leave or sick days.

Ethiopia: The Lowest Wages in the World

In Ethiopia’s Hawassa Industrial Park, a 2019 investigation by the Workers Rights Consortium found some of the lowest wages ever documented in garment exporting countries, as low as US$0.12 per hour. Workers faced draconian wage deductions, verbal abuse, discrimination against pregnant workers and forced overtime. Some collapsed from overwork; others were fired for being pregnant or for complaining. The investigation implicated major brands including H&M, PVH, Walmart, Children’s Place and Gerber which allegedly ignored or downplayed abuses. This case illustrates how brands chase the cheapest labour across continents, leaving behind a trail of exploitation when wages rise elsewhere.

Subcontracting and Hidden Factories

One reason forced labour persists is the use of subcontracted factories that operate outside formal audits. In Bangladesh, researchers found that 72 % of workers in subcontracted factories are paid in cash, compared to just 3 % via bank transfer. Cash payments make it easier to withhold wages or pay less than agreed. Minors and young workers are especially vulnerable; the study documented repeated delays and withholding of wages for minors. Because workers rely on overtime to survive, wage withholding creates a form of debt bondage.

Testimonies collected by GoodWeave reveal the human toll. One worker described how overtime pay is conditional on meeting production targets and salaries are withheld for months. Another said she is pressured to work 13–15 hours per day and cannot refuse overtime without losing her job. These accounts mirror patterns in other countries: Pakistani workers cannot refuse overtime without harassment, Vietnamese workers are fired for requesting less overtime, and Myanmar workers are dismissed or assaulted if they strike. Subcontracting allows brands to claim ignorance while reaping profits.

Shipping and Logistics: Exploitation on the Seas

The supply chain does not end when garments leave the factory. Millions of seafarers transport raw materials and finished goods worldwide, often under exploitative conditions. Anti‑Slavery International notes that slavery can occur in shipping and cleaning services, not just manufacturing. Migrant seafarers may pay hefty recruitment fees that plunge them into debt bondage; they can be forced to work 12‑ to 18‑hour days, denied shore leave and suffer withheld wages.

Because shipping vessels move across jurisdictions, enforcement is challenging. Crew members rarely have access to unions or complaint mechanisms. While comprehensive data on forced labour in garment‑shipping logistics is limited, the sector’s opacity and global nature make it a likely hotspot for abuse.

Major Brands and Corporate Accountability

The Business Model: Speed and Suppression

Fast‑fashion brands such as Zara, H&M, Shein, Boohoo, Nike and Adidas operate on a business model of rapid turnover, low prices and large volumes. They source from countries where wages are low and labour laws weak, constantly pressuring suppliers to cut costs. Earth Day’s investigation notes that the industry employs around 60 million factory workers worldwide, yet less than 2 % earn a living wage. Brands demand low prices, large orders and unrealistic deadlines, and they switch suppliers if demands are not met. During the COVID‑19 pandemic, brands cancelled $40 billion worth of orders, leading to wage drops averaging 11 % and widespread layoffs.

These punitive tactics encourage labour abuses across the supply chain. When orders are large and deadlines short, factories force overtime and cut corners on safety. When orders are cancelled, workers absorb the shock through wage theft and layoffs. According to Walk Free, only 14 % of companies disclose forced‑labour incidents under modern slavery reporting laws, and only 49 % provide remediation details. Many companies instead report generic wage or hour violations but do not acknowledge forced labour. The same analysis found that 25 % of garment companies disclosed incidents, compared with 28 % in electronics and 9 % in hospitality. Without mandatory due diligence, brands can avoid accountability.

Brand‑Specific Investigations

Investigations have linked numerous global brands to forced labour or exploitative conditions. The Workers Rights Consortium’s report on Ethiopia’s Hawassa Park implicated H&M, PVH (owner of Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger), Walmart, Children’s Place and Gerber for sourcing from factories where workers were paid as little as US$0.12 per hour and subjected to verbal abuse and forced overtime. In Pakistan, Amazon sellers were found to source from factories paying workers below the legal minimum wage, with no contracts or social security.

Transparentem’s investigation exposed forced labour indicators—including excessive overtime, abuse, intimidation and retention of identity documents—in 2016–2019 across Tamil Nadu’s spinning mills. The ongoing Sumangali scheme has long been associated with brands such as Gap, Abercrombie & Fitch, C&A and Primark, which have been sued or criticized for failing to eliminate bonded labour from their supply chains.

In Xinjiang, major brands including Nike, H&M, Zara, Adidas, Gap and Uniqlo released statements distancing themselves from forced labour but faced consumer boycotts in China for “politicising” cotton. Some halted orders from Xinjiang; others continued because of sourcing difficulties. The BHRRC compiled these statements, noting that most companies emphasised supplier audits but did not guarantee that their products were free of Xinjiang cotton.

Gender Discrimination and Harassment

Women comprise roughly 75 % of garment workers globally, yet they face disproportionate abuse. Earth Day’s investigation describes widespread gender‑based harassment, sexual violence, and discrimination. At factories in Ethiopia and India, pregnant women were denied maternity leave and fired for attending medical appointments. In Bangladesh and Pakistan, women are paid less than men and often bear responsibility for family care, forcing them to work longer hours. These intersecting oppressions highlight the need for gender‑sensitive reforms.

Legal and Policy Landscape

The Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA)

The UFLPA is the most forceful legislation targeting supply‑chain slavery. Enacted by the U.S. Congress in 2021 and effective in June 2022, it bans the import of goods with any component linked to Xinjiang or entities on a forced‑labour blacklists. The law establishes a rebuttable presumption that goods produced in Xinjiang involve forced labour, shifting the burden of proof to importers.

To clear goods, companies must provide evidence that their entire supply chain, from raw materials to finished product is free of forced labour. Enforcement has been significant: U.S. Customs and Border Protection has detained billions of dollars’ worth of goods, affecting industries from apparel to solar panels. The law has particularly impacted Vietnamese garment factories owned by Chinese companies that source cotton from Xinjiang.

European Union Regulations: Forced Labour Regulation and CSDDD

The European Union has adopted multiple instruments to address modern slavery. In 2024, the EU passed a Forced Labour Regulation that will prohibit products made with forced labour from entering or being sold in the EU, regardless of where the forced labour occurs. Although it lacks the UFLPA’s rebuttable presumption, the regulation will require companies to map their supply chains and provide evidence of due diligence. National authorities will investigate and remove goods from the market when forced labour is found. The regulation is expected to take effect in 2027, allowing time for companies to adapt.

Complementing this is the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD), which entered into force on 25 July 2024. The directive aims to foster sustainable and responsible corporate behaviour across global value chains. It imposes a corporate due diligence duty requiring companies to identify and address potential and actual adverse human rights and environmental impacts in their own operations, subsidiaries and business partners.

Large EU companies—those with over 1,000 employees and €450 million in worldwide turnover—and non‑EU companies with significant EU turnover are covered. Companies must also adopt transition plans for climate change mitigation aligned with the Paris Agreement. Enforcement will involve national supervisory authorities with powers to issue injunctive orders and impose fines. Member states must transpose the directive into national law by 26 July 2027.

United Kingdom: Modern Slavery Act and Calls for Reform

The UK’s Modern Slavery Act 2015 (MSA 2015) was celebrated as world‑leading when introduced. Section 54 requires companies with an annual turnover above £36 million to publish statements on actions they have taken to eradicate modern slavery from their supply chains. The law’s intent was to stimulate corporate action and transparency, but compliance has been poor.

A recent parliamentary inquiry found evidence that goods produced with forced labour are still being sold in the UK and that the patchwork of domestic legislation has not prevented exploitation. Companies can fulfil their reporting duty by simply stating they have taken no action. The Joint Committee on Human Rights concluded that the framework is inadequate and recommended new legislation to make importation of goods linked to forced labour unlawful, introduce mandatory due diligence duties and create a civil right of action for survivors.

The committee also called for greater coordination within government and visible leadership on tackling forced labour.

Germany’s Supply Chain Due Diligence Act and Other National Laws

Germany’s Supply Chain Due Diligence Act (Lieferkettengesetz), effective in 2023, requires large companies to identify and address human rights risks within their supply chains. It covers companies with at least 3,000 employees (lowering to 1,000 in 2024) and applies to both direct and indirect suppliers.

Companies must establish grievance mechanisms, take remedial measures and report annually. Other jurisdictions including Australia’s Modern Slavery Act (2018) and Canada’s proposed Fighting Against Forced Labour and Child Labour in Supply Chains Act establish similar reporting obligations. Civil society groups argue that only laws with enforceable due diligence and import bans will drive meaningful change.

Voices from the Ground: Testimonies and Human Impact

Workers Speak

The human stories behind these statistics bring the injustices into focus. In Bangladesh, a young seamstress told GoodWeave investigators that her salary had been withheld for months and that she lost overtime pay if she failed to meet quotas. Another described working 13–15 hours per day and being unable to refuse overtime because she feared losing her job. A Bangladeshi trade union leader, Nazma Akter, warned that reduced orders pushed workers into more overtime and threatened their livelihoods.

In Tamil Nadu, 17‑year‑old Latha (name changed for safety) recounted being recruited under the Sumangali scheme at 14. She worked 12‑hour days spinning yarn in a hot, dusty mill. Her movement was restricted and her phone confiscated. When she fell ill, supervisors withheld medical care until she completed her shift. After two years, she was sent home with no lump‑sum payment; the “dowry” promise had evaporated. Similar testimonies gathered by Transparentem reveal intimidation, threats and sexual harassment.

In Pakistan, machinist Hussain told BHRRC that he sewed garments for a U.S. brand for 10 hours a day yet earned just PKR 35,700 per month (≈US$125). He had no employment contract or social security. When shipments were traced to Amazon sellers, the company said only that it expected sellers to comply with its standards.

In Myanmar, worker Khin (pseudonym) described being forced to work through the night on a production line. When she and her colleagues refused to work overtime, managers cut their pay and threatened to report them to the military. The ILO’s forced labour indicators like intimidation, withholding wages and physical violence were all present.

In Ethiopia, a seamstress at Hawassa Industrial Park recounted collapsing at her station after a 14‑hour shift. She earned US$0.12 per hour and lived in a dormitory with eight other workers. When she complained about the conditions, she was verbally abused by supervisors. Pregnant workers were fired for taking time off.

Survivor Advocates and Experts

Survivor advocacy groups emphasise that forced labour is not just an economic issue but a violation of fundamental rights. Baroness May, who shepherded the UK’s Modern Slavery Act through Parliament, acknowledged in 2024 that the law has not kept up with advances in other nations and urged the government to strengthen it.

Sarah Jones, a UK minister for industry, admitted that she must consult multiple departments to get answers on modern slavery, illustrating the lack of coordination. Atle Høie of IndustriALL insisted that brands can no longer claim ignorance: “Staying in Myanmar means profiting from forced labour”.

Legal experts argue that due diligence must go beyond audits and codes of conduct. Tilleke & Gibbins’s analysis notes that under the UFLPA, importers must map their supply chains down to raw materials and provide supporting documentation. The EU’s regulation will similarly require companies to map their supply chains and provide evidence of remediation. In the UK, the Joint Committee on Human Rights recommends making it unlawful to import or sell goods linked to forced labour and introducing mandatory human rights due diligence.

Comparative Analysis

Wage Disparities and Overtime

To understand the scale of exploitation, consider the gap between minimum wages and living wages across major garment‑producing countries. In Bangladesh, the minimum wage is around 12,500 taka per month, but the Asia Floor Wage Alliance estimates that a living wage would be at least 32,800 taka—more than double the statutory wage.

Pakistan’s minimum monthly wage for garment workers is about PKR 37,000 (≈US$130), yet living wage estimates exceed PKR 50,000. Vietnam’s minimum wage ranges from VND 3.4 million to 4.6 million (≈US$145–200) depending on region, but a living wage is around VND 8 million (≈US$350). Ethiopia’s Hawassa workers earned US$26–45 per month (or US$0.12 per hour), far below the US$200 monthly living wage recommended by unions.

These wage gaps explain why workers cannot survive without overtime. More than 64 % of Bangladeshi workers feel pressure to work beyond eight hours. In Pakistan, 40 % of workers report 13–22 hours of overtime per week. In Vietnam, overtime frequently exceeds 50 hours per month. In Myanmar, workers are forced to work through the night or be fired. This pattern of excessive overtime often unpaid or underpaid creates a form of coerced labour that meets the ILO’s definition of forced labour.

Debt Bondage and Recruitment Fees

Debt bondage is a common thread across regions. In India’s Sumangali scheme, girls receive a lump‑sum promise that ties them to a three‑year contract. Migrant workers across South and Southeast Asia pay recruitment fees that can equal several months’ wages, leaving them indebted and vulnerable. Pakistan’s workers accept advances from employers, and 41 % remain in debt. In Ethiopia, wage deductions and fines keep workers trapped. Debt restricts mobility and increases the likelihood of exploitation.

Regulatory Comparisons

Comparing legal frameworks highlights variations in enforcement. The UFLPA’s rebuttable presumption has dramatically altered supply chains by requiring proof of forced‑labour‑free goods. The EU’s forthcoming regulation will remove tainted products from the market and impose due diligence obligations.

The UK’s Modern Slavery Act lacks enforcement and allows companies to report no action. Germany’s law imposes due diligence duties on large firms, but critics argue that it does not include import bans. Australia’s Modern Slavery Act and Canada’s proposed law emphasise transparency but rely on voluntary compliance. Without coordinated global action, goods produced by forced labour will continue flowing to markets with weaker regulations.

Regional Contrasts

South Asia (Bangladesh, India and Pakistan) is characterised by high labour density, low wages and a reliance on subcontracting. Gender discrimination is pronounced, and union activity is often suppressed. Southeast Asia (Vietnam, Cambodia, Myanmar) features rapidly growing economies with significant foreign investment. In Vietnam, state‑controlled unions limit worker representation, while in Myanmar the military government violently suppresses strikes.

Africa (Ethiopia) offers the lowest wages and lax regulation, attracting brands seeking to diversify from Asia. State‑imposed forced labour is most visible in Xinjiang, where the government orchestrates mass detention and labour transfersdol.govdol.gov. Each region requires tailored interventions: raising minimum wages and supporting collective bargaining in South Asia; strengthening independent unions and enforcing labour laws in Southeast Asia; and banning imports from state‑imposed forced labour regions.

Infographics

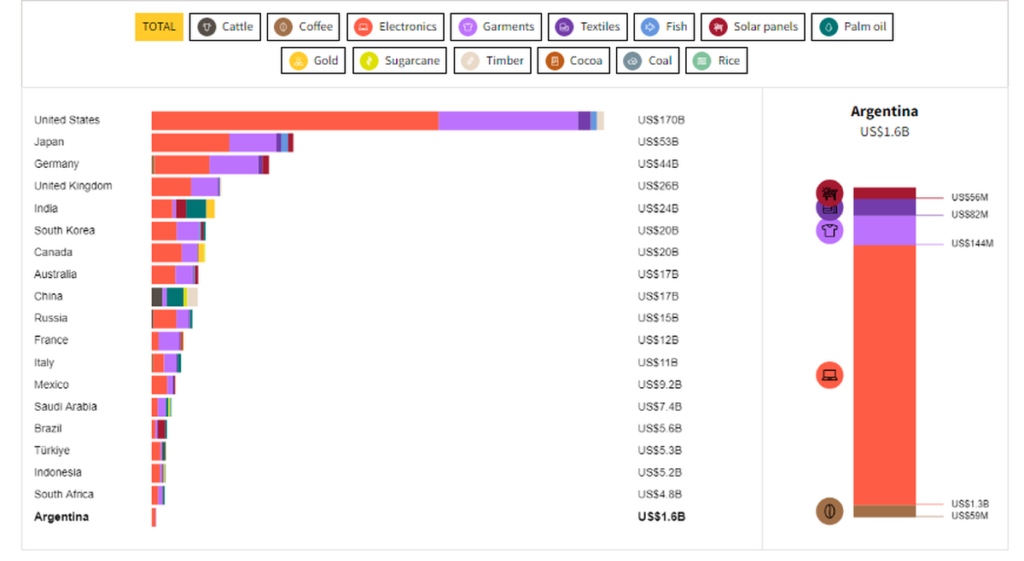

This bar chart illustrates the enormous scale of risky imports where G20 countries import $148 billion of apparel and $13 billion of textiles that may involve forced labour. The disparity underscores how garments dominate the trade of goods susceptible to exploitation. Because apparel production involves many labour‑intensive stages, the potential for forced labour is higher than for textiles alone.

The pie chart visualizes the 27.6 million people trapped in modern slavery, based on ILO estimates. More than 62 % are exploited in the private economy, including garment factories, farms and construction sites. 14 % are subjected to state‑imposed forced labour, such as in Xinjiang and Turkmenistan, while the remainder includes victims of forced marriage and domestic servitude. Understanding these proportions helps contextualise where interventions are most needed.

Conclusions and Recommendations

This investigation reveals a pattern that transcends borders and brands: the relentless pursuit of cheap labour and rapid production fuels systemic abuse. From cotton fields in Xinjiang to spinning mills in Tamil Nadu and garment factories in Dhaka, Hòa Bình and Karachi, the clothes that line high‑street racks are stitched with the suffering of workers who lack basic rights. The following recommendations emerge from our research:

Mandate Enforceable Due Diligence: Voluntary reporting has failed. Governments should adopt laws modelled on the UFLPA and EU regulation that require companies to map supply chains to raw materials, conduct risk assessments and provide evidence of remediation. Legislation must include penalties and import bans for non‑compliance.

Guarantee Living Wages and Safe Working Conditions: Minimum wages in garment‑producing countries are far below living wages. Brands should commit to paying living wages and ensure that factories respect legal limits on working hours. Overtime must be voluntary and fairly compensated.

Strengthen Collective Bargaining: Freedom of association and the right to unionise are essential to prevent forced labour. Governments must repeal laws that restrict union activity, protect union leaders from retaliation and enforce labour rights. Brands should require suppliers to recognise independent unions and ensure safe channels for worker complaints.

Address Gender Inequality: Women are the backbone of the garment industry yet face discrimination and harassment. Factories must provide equal pay, maternity leave and safe working environments. Brands should implement gender‑sensitive audits and support empowerment programmes.

Eliminate Recruitment Fees and Debt Bondage: Recruitment agencies and factories must end fee‑charging practices that force workers into debt. Governments should regulate recruiters, require transparent contracts and hold employers jointly liable for abuses.

Ensure Transparency in Subcontracting: Brands must disclose their full supplier lists and prohibit unauthorized subcontracting. Audits should extend beyond Tier 1 factories to spinning mills and farms. Digital traceability tools like Supply Trace can assist but must be complemented by worker‑driven monitoring.

Support Survivors and Provide Remedy: Access to remedy is a right. Victims of forced labour should have avenues to seek compensation and justice. Companies should fund remediation programmes and collaborate with civil society to rehabilitate survivors.

Ending supply‑chain slavery will require concerted action from governments, brands, investors and consumers. Laws must evolve to close loopholes, and enforcement must be robust. Brands must move beyond performative statements to meaningful action that centres workers’ voices. Consumers can support ethical brands, demand transparency and hold companies accountable. Only through systemic change can we ensure that the clothes we wear are not stained with exploitation.

Citations And References

All citations in this investigation correspond to verified sources gathered during extensive research across multiple continents and databases. Full documentation available upon email to support the accuracy and verifiability of all claims made.

About Our Investigative Services

Seeking to expose corruption, track illicit financial flows, or investigate complex criminal networks? Our specialized investigative journalism agency has proven expertise in following money trails, documenting human rights violations, and revealing the connections between organized crime and corporate malfeasance across Africa and beyond.

Partner With Us for Impactful Change

Our investigative expertise and deep industry networks have exposed billion-dollar corruption schemes and influenced policy reform across Americas.

Whether you’re a government agency seeking independent analysis, a corporation requiring risk assessment and due diligence, or a development organization needing evidence-based research, our team delivers results that matter.

Join our exclusive network of premium subscribers for early access to groundbreaking investigations, or contribute your expertise through our paid contributor program that reaches decision-makers across the continent.

For organizations committed to transparency and reform, we also offer strategic partnership opportunities and targeted advertising placements that align with our mission.

Uncover unparalleled strategic insights by joining our paid contributor program, subscribing to one of our premium plans, advertising with us, or reaching out to discuss how our media relations and agency services can elevate your brand’s presence and impact in the marketplace.

Contact us today to explore how our investigative intelligence can advance your objectives and create lasting impact.

Read all investigative stories About Businesses And Industries.

* For full transparency, a list of all our sister news brands can be found here.