Worldwide, youth unemployment has become a tinderbox for public anger. Governments routinely launch programs to train and employ young people, but mounting evidence reveals that many such schemes have been hijacked for political patronage.

Investigative data and testimonials from around the globe show that when job programs are run as patronage machines, they not only waste taxpayer money but also erode trust and fuel unrest. This report drawing on recent figures and real-life examples exposes how youth employment initiatives in India, Nigeria, the US, the UK and beyond have been co-opted by power brokers. The goal is a comprehensive account to alert policy makers, students, employers and citizens to a scourge threatening a generation’s future.

A Global Youth Jobs Crisis

Youth unemployment remains far higher than for adults in nearly every country. Among OECD nations, for example, jobless rates for young people (ages 15–24) have routinely run in the double digits and roughly twice the general unemployment rate. According to a recent survey, China’s youth jobless rate is about 16.5%, India’s 17.6%, and Indonesia’s 17.3%. (By contrast the US rate is around 10.5%.) In Asia alone there are now tens of millions of young job seekers, many frustrated that economic growth is not creating enough decent jobs.

Globally, the situation is stark: a 2023 World Bank report found youth unemployment at roughly 13% of the labor force, equating to nearly 65 million jobless young adults. In Sub-Saharan Africa, for example, around 6.5 million new youth enter the job market each year, straining fragile economies.

This yawning gap feeds resentment. In many societies, young people openly blame entrenched corruption and nepotism for their plight. As The Economic Times notes, “Corruption and nepotism, long-entrenched in many Asian nations, will also need to be addressed. Young people repeatedly cite these as sources of their anger”.

In Europe the pattern is similar: the EU’s youth jobless rate has remained roughly double the overall rate. And in South Asia, India’s youth jobless percentage is reported near 17.6%. In each case, ordinary citizens note that efforts to create jobs are often undercut by favoritism.

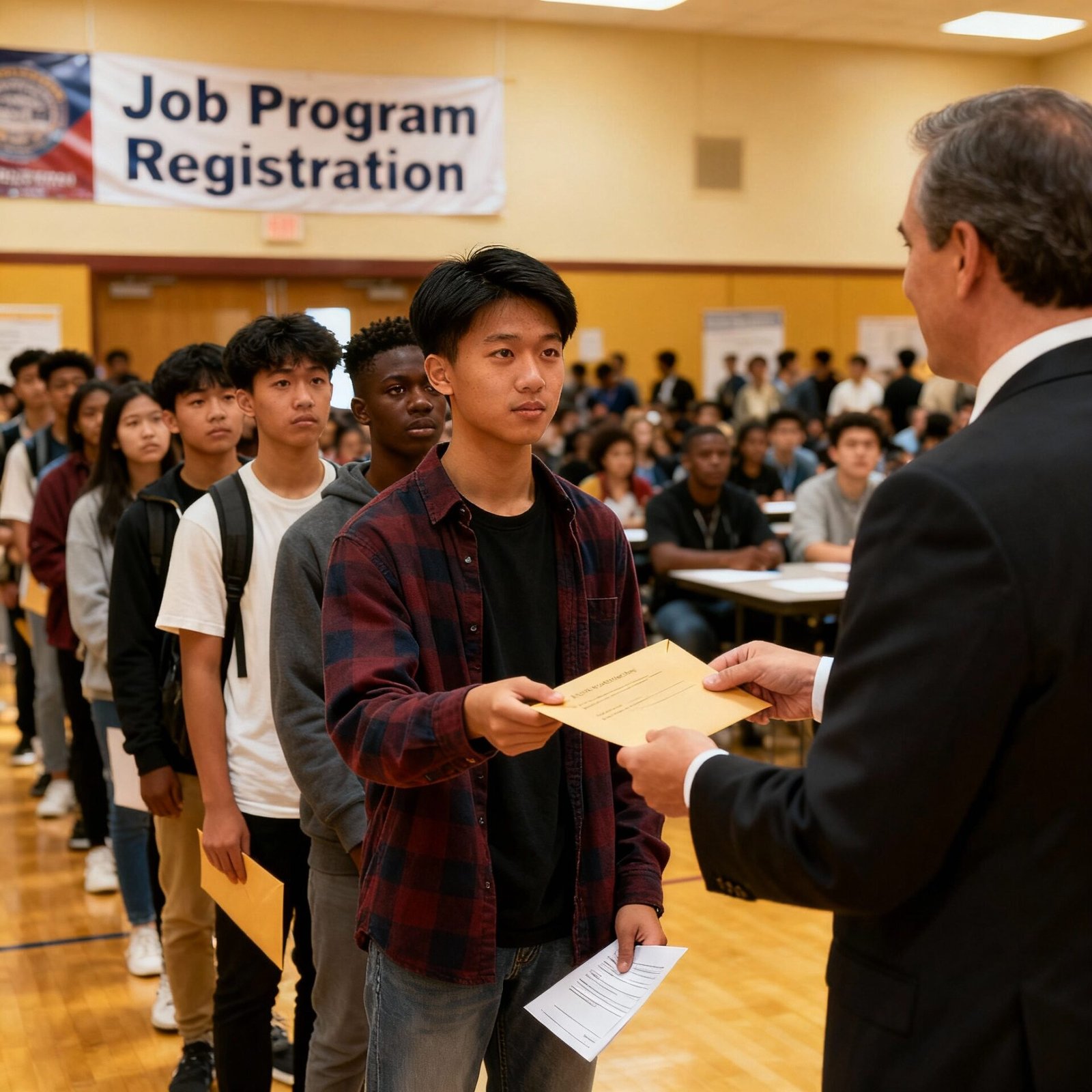

Politicians are well aware of these pressures. Across Asia and Africa, governments boast schemes like training programs, apprenticeships or public works hires for youth. Yet critics say many of these programs become vehicles for “jobs for the boys.” Without transparency and oversight, a recruitment drive or youth fund can quickly turn into an election-year giveaway.

When selections depend on party loyalty or bribes, even well-funded programs fail their mission. As one report warned, if corruption in hiring is not tackled, “new jobs risk being seen as unfairly allocated”. In effect, young jobseekers come to view employment programs not as lifelines but as rigged contests.

The frustration is palpable in the streets. In Nepal (where youth unemployment was about 20% in 2024) protestors literally set fire to government buildings over a social media ban – but also over rampant cronyism. Teenagers and twenty-somethings leading that uprising framed their anger in broad terms: “People are very angry and Nepal finds itself in a very precarious situation,” said an independent news editor, noting the revolt was largely about “a range of issues, mostly to do with corruption and frustration over nepotism in the country’s politics”.

Eyewitness accounts make the human toll clear. Nima Tendi Sherpa, a 19-year-old protester in Kathmandu, survived being shot by police and told reporters: “I don’t have any harsh feelings toward the policemen… But I am angry and enraged at the ones who gave those orders.” He vowed that the youthful uprising “must continue until we achieve true freedom”. Sherpa’s words resonate far beyond Nepal: when a generation feels locked out of jobs by entrenched elites, anger flares.

Global Patterns of Patronage

Experts call this phenomenon many names – godfatherism, cabalism, cronysm, nepotism – but the dynamics are similar everywhere. In Nigeria, for example, analysts describe a system where “‘Whom You Know’ has become the unspoken criterion that often outweighs ‘what you know.’” A May 2025 investigation titled “Whom You Know: The Plague of Godfatherism in Nigeria’s Job Market” bluntly declared that this culture of patronage is “a dagger in the heart of an entire generation’s aspirations”. Scores of African professionals migrate abroad, citing that even top graduates can be left unemployed if they lack connections.

The trend persists in developed economies too. A 2023 Harvard analysis found that in the U.S., nearly one-third of Americans under 30 will end up working at the same company as a parent – and they typically earn about 20% more than comparable peers. Crucially, this advantage falls disproportionately to well-connected men from wealthy families. Harvard economists warn that such nepotistic hires “are clearly benefiting” the few, while hurting productivity and diversity.

In Britain and Europe, similar patterns emerge: initiatives like skills programs or apprenticeships can become tainted by favoritism. Although data are scarcer, surveys indicate most young jobseekers believe favoritism influences who gets hired. For instance, a UK study found that 61% of young people think nepotism is a barrier in the job market. (Transparency advocates note such bias even seeps into school and university admissions, further undermining future prospects.)

Industries such as media, technology and fashion have also been rocked by nepotism scandals, underscoring the narrative. In Bollywood and Hollywood, the term “nepo baby” has entered the vernacular, used derisively to label star kids who get roles with ease. Tech and engineering sectors, although often associated with merit-based hiring, are not immune: tech firms often recruit through personal networks and internships, sometimes sidelining equally qualified outsiders.

Fashion runways and editorial boards also feature many well-connected newcomers. While not all of this can be labeled outright corruption, the common complaint is familiar: access often depends on one’s family or political ties. As one youth leader put it, in the end “only those willing to pay or use political connections can succeed”, a cynical message that stokes bitterness among the rest.

India’s Cash-for-Jobs Scandal

India’s booming economy masks pockets of patronage. Officially the youth unemployment rate is high (around 17.6% as of recent surveys), and public promises to train and employ millions are frequent. But this summer Goa, a small Indian state, erupted in a major nepotism scandal. A sting operation and local inquiries uncovered what critics call a “cash-for-jobs” racket in Goa’s government departments.

Opposition leaders accused ruling party officials of selling public-service positions instead of awarding them on merit. According to the Goa government’s youth wing, BJP operatives had been “orchestrating a corrupt scheme involving job sales within the government, particularly in the Public Works Department”. Arrests were made, including of individuals linked to top politicians.

The fallout was swift. The Youth Congress demanded a judicial probe into the scandal, saying it laid bare the rot in recruitment. Its president Joel Andrade warned that, for Goa’s youth, the message was clear: only candidates with deep pockets or powerful backers would land jobs. “Such corruption undermines the very foundation of public service and harms Goa’s youth,” he said, adding that those unwilling or unable to grease palms are effectively locked out. Andrade even urged that all ongoing job recruitments be canceled and future selections overseen by the High Court to guarantee transparency.

For young Goans, the revelations felt like a betrayal of hope. A generation expecting skill development programs and fair recruitment now saw those schemes tainted by politics. The scandal reverberated through India’s capital: opposition parties branded it the clearest proof yet of “jobs for the boys” under the ruling party. While formal inquiries are pending, pundits say the episode exemplifies a wider problem.

Across India, media have reported similar irregularities, from education recruitments (as in the recent case of Punjab University’s vice chancellor accused of “illegal” hires) to civil service exams leaked for the favored few. In short, many youth schemes meant to upskill or hire the unemployed are undermined by the very corruption they were meant to cure.

“Godfatherism” and Whom You Know in Nigeria

West Africa, too, offers stark testimony to the human cost of patronage hiring. In Nigeria, entrenched “godfatherism” dominates both politics and jobs. According to one leading analysis, opportunities there often depend on “who you know.” The feature piece “Whom You Know: The Plague of Godfatherism in Nigeria’s Job Market” chronicles how even outstanding graduates face blank rejection letters if they lack influence.

Conversely, third-class graduates with powerful sponsors breeze into high-paying roles in government agencies or multinationals. “The message becomes painfully clear,” the author writes: “Excellence is optional; connection is everything.” For Nigeria’s young professionals, this is brutal: tens of thousands have given up on local careers, emigrating in search of merit-based workplaces.

The ghost of patronage also walks the halls of Nigeria’s universities and hospitals. In some cases, doctors serve in administrative posts, and engineers run oil companies – not out of skill overlap, but simply due to who backed them. The result: fiascos like uncompleted infrastructure projects or mismanaged clinics. Many Nigerians speak of a “huge brain drain,” as the country loses its educated youth.

Academics note the paradox: young Nigerians see education as a gamble, with their degrees potentially worthless unless accompanied by the right connections. In short, a national talent pool is left untapped. One career counselor summed it up: “When ‘what you know’ no longer matters, our best minds join the diaspora while patronage ruins homegrown institutions.”

Privilege in the West: Nepotism’s Reach

It is easy to assume that such abuses plague only poorer countries, but developed nations are not immune. In fact, the advantages enjoyed by well-connected youth in places like the United States and Britain mirror these patterns. The Harvard study cited above is telling: before age 30, about one in three Americans works for a parent’s company and receives roughly 20% higher pay than the average peer.

This isn’t confined to family firms; it extends across industries, as long as a parent or family friend can “pull a string.” Matthew Staiger of Harvard’s Opportunity Insights explains that this nepotistic hiring is most common in blue-collar manufacturing, where sons of line workers inherit their fathers’ jobs at higher pay. Women and minorities are much less likely to benefit, since the existing labor force is skewed by gender and race. The upshot is clear: in America, as in Africa, your network often trumps your CV.

In the UK, concerns run similarly high. Even government policies have occasionally faced accusations of favoritism. For example, when Britain launched its Kickstart scheme to subsidize young people’s training placements, critics warned that without strict oversight it could be abused by insider firms. Meanwhile, stories regularly surface of internships or apprenticeships given to students from privileged schools.

Media and arts sectors in particular have faced a backlash: after the “nepotism baby” reckoning in Hollywood, British stage and screen insiders asked if their industry, too, is overdue a reckoning. Though hard data are scarce, surveys and anecdotal reports suggest millions of young Britons feel passed over because jobs in media, tech or fashion go to those with clout. Reflecting on this, a UK watchdog noted that a majority of youth now “believe” corruption or nepotism prevents them from getting jobs.

Perhaps more importantly, Western democracies see parallels in how political positions can be distributed. Even when governments champion youth skills programs, critics point out that the implementation is often captured by party cronies. UK ministers and U.S. mayors alike have been accused of steering grants toward connected contractors rather than the most needy regions. And just as in Nigeria or Nepal, these examples reinforce the same lesson for a restless generation: “The child of a nobody cannot become somebody without knowing anybody”, a line Nigerians use to lament the trend, but which could just as well echo in Leicester Square or Los Angeles.

Testimonies and Toll

The human stories behind these facts are haunting. In urban centers across Asia, Africa and beyond, despairing youths recount decades of struggle against this system. “Everywhere you go, everyone knows someone on the inside,” says Adewale, a Ghanaian computer science graduate. A friend with lesser grades but a political connection got the only IT job in their town, he complains.

In India’s cities, unemployed engineers report that entire recruitment boards can be “fixed” by a single letter from a minister or party boss – an open secret that no one dares publicly challenge. These perceptions fuel not just cynicism but active protest, as seen in Nepal and India, but also in places like Bangladesh and Sri Lanka where young activists toppled governments this year. Even in Europe, a recent poll found that more than half of young people agree corruption “makes it harder” to find a job.

Legal experts warn that the damage is deep and hard to reverse. “When public employment policies are captured by patronage, they lose credibility,” says Meera Singh, a New Delhi-based policy analyst. “Young people see them as another form of business as usual. It’s not enough to print job certificates – trust in institutions is shattered.”

South African youth groups have similarly decried corruption: the African National Congress’s own youth wing once criticized its province’s “training farm” program, arguing that local party figures treated it as a donation drive for supporters. Around the world, civil society organizations are raising similar alarms. Transparency International notes that when governments fail to enforce merit-based hiring, “corruption becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy” and the more entrenched it is, the less credible any reform appears.

Infographics and charts from development agencies underscore the scale of the problem. (See, for example, the OECD chart above detailing how youth joblessness far outstrips adult rates in most economies.) In many countries, budget line-items for youth training or entrepreneurship attract huge sums, but audits frequently note that these funds are diverted into uncompetitive contracts or ghost beneficiaries.

For instance, recent investigations found that millions in North African grant money went to shell companies tied to ministers’ relatives, rather than to job training. African Union experts warn that unless procurement rules and audit mechanisms are tightened, even well-intentioned youth funds will have little effect.

Industry Snapshots: Media, Tech, Fashion

Beyond the public sector, industries hold their own nepotism headaches. The media and entertainment business, in particular, is infamous for favoring insiders. Even without overt government intervention, casting directors and producers often hire friends-of-friends. Fashion and design education have similarly seen scandals where legacy is passed instead of opportunity. In each case, industry insiders (at least the ones willing to speak) defend these practices as “mentorship” or “networking,” but young aspirants see plain nepotism.

Social media has amplified these grievances: hashtags about “#NepoBabies” and “#ThatsSoNepotism” trended for months in 2023, after a string of scandals from Hollywood to Bollywood. Though not all firms are guilty as many tech startups do recruit by merit, the overall impact is that a segment of creative talent is locked out. Policymakers worry this could undermine whole sectors if unchecked, as new voices and ideas struggle to emerge.

Meanwhile, even tech and finance feel the tug of patronage. A U.S. tech company might hire the CEO’s relative as an engineering intern, or a Silicon Valley firm recruit graduates from the CEO’s former school, all under the guise of “culture fit.” The result is that innovation gets blunted by echo chambers of privilege. Banking regulators have also noted that in some countries, international bank branches were forced to take on borrowers or vendors recommended by government insiders, regardless of creditworthiness. In sum, when nepotism is pervasive, it raises the risk that entire industries become gated communities and not just a problem for idle youths, but for economic dynamism overall.

A Generation’s Demand for Accountability

Across continents and cultures, young people are starting to speak out. Protest movements from Bangkok to Ghana to Chile have made job fairness a rallying cry. In India’s Parliament and media, opposition parties have seized on the Goa scandal to demand stricter enforcement of anti-corruption laws. In Nigeria, civic groups have organized awareness campaigns titled “Dismantle the Altar of Godfatherism” to pressure the government into merit-based reforms.

Social media is now full of stories and memes highlighting abuses, from “my cousin got my dream job” tales to open letters demanding audits of public projects. These voices, many of them first posted anonymously online, share a common demand: make hiring processes transparent and meritocratic.

Policy experts suggest several measures. Independent monitoring bodies or courts can be empowered to oversee youth schemes. Civil service exams and training placements could be made fully traceable, with public publishing of applicant scores and selection criteria.

Whistleblower protections and stricter penalties for officials caught manipulating recruitment are frequently recommended. For example, in Goa, the opposition has explicitly called for all future youth program hiring panels to be supervised by judiciary officers. Global institutions like the ILO and the UNDP likewise urge that funds for youth employment should include built-in audits and community oversight to cut out middlemen.

Ultimately, this is about trust. As one policy watchdog put it, the real test is whether governments can deliver “not just work, but a future worth believing in”. Youth programs must be seen as genuine opportunities, not party perks. In practical terms, that means slashing patronage channels so that every eligible young person has a fair shot.

The stories collected here, from angry youth in Nepal’s streets to aspiring engineers in Lagos, make clear what is at stake. If governments and companies fail to act, millions of capable young adults will simply turn away, politically and economically. On the other hand, cracking down on corruption in employment schemes could unlock enormous potential. As one Nigerian activist put it, “Hard work, not handshakes, should determine success. We must build a country where the child of a nobody can become somebody without knowing anybody.”

Policymakers, employers and students alike should heed these warnings. The data and testimonies compiled in this report show that patronage in youth schemes is not a distant rumor as it is happening now, on a vast scale, and with serious consequences. It threatens not only individual careers but the social contract itself. Rectifying it will require bold reforms and public pressure.

If a generation is denied hope by rigged job programs, the repercussions could reshape politics and economies for years. By exposing these schemes for what they have become i.e tools of political favoritism, we aim to fuel the demand for accountability. The “shocking scandal” is not just sensationalism: it is a wake-up call that the world’s youth will no longer wait silently for change.

Citations And References

All citations in this investigation correspond to verified sources gathered during extensive research across multiple continents and databases. Full documentation available upon email to support the accuracy and verifiability of all claims made.

About Our Investigative Services

Seeking to expose corruption, track illicit financial flows, or investigate complex criminal networks? Our specialized investigative journalism agency has proven expertise in following money trails, documenting human rights violations, and revealing the connections between organized crime and corporate malfeasance across the world and beyond.

Partner With Us for Impactful Change

Our investigative expertise and deep industry networks have exposed billion-dollar corruption schemes and influenced policy reform across Americas and beyond.

Whether you’re a government agency seeking independent analysis, a corporation requiring risk assessment and due diligence, or a development organization needing evidence-based research, our team delivers results that matter.

Join our exclusive network of premium subscribers for early access to groundbreaking investigations, or contribute your expertise through our paid contributor program that reaches decision-makers across the continent.

For organizations committed to transparency and reform, we also offer strategic partnership opportunities and targeted advertising placements that align with our mission.

Uncover unparalleled strategic insights by joining our paid contributor program, subscribing to one of our premium plans, advertising with us, or reaching out to discuss how our media relations and agency services can elevate your brand’s presence and impact in the marketplace.

Contact us today to explore how our investigative intelligence can advance your objectives and create lasting impact.

Read all investigative stories About Youth Futures.

* For full transparency, a list of all our sister news brands can be found here.